You are here

Home ›Lest We Forget, 1916 And All That: What has it got to do with us?

Two years or so ago we set out to counter the view of the 1st World War presented to us by the official commemorations which in Britain have received much media coverage.[1] At a time when the UK Treasury saw fit to extend “the age of austerity” to at least 2018, the centenary celebrations were seized on by Cameron, the PR expert, as part of his “We’re all in it together” deceit. Government money has been thrown at schools, artists, local authorities and any tin pot club or society with a World War One project to encourage them to join in the game of strengthening grass roots nationalism. (“The centenary of the First World War offers a unique opportunity for the nation to _understand, remember and recognise the debt we owe to those who served.”_ So the official patter runs.) No doubt this stoking of basically little-Englander nostalgia contributed to the sentiment behind the Brexit vote, a warning to the ruling class that nationalism can divide as well as unite. A reminder too that, even in an age when the ruling class can draw on supra-sophisticated propaganda techniques, there is a limit to the effectiveness of official spin when material reality constantly tells people it’s simply not true.

If “we’re all in this together” has lost credibility amongst the working class today, in 1916, as the war that would “end all war”[2] extended globally with a ‘casualty rate' on a truly industrial scale and conditions for the working class on the ‘home front’ (wherever that happened to be) became ever harsher, signs of grass roots disaffection were mounting.

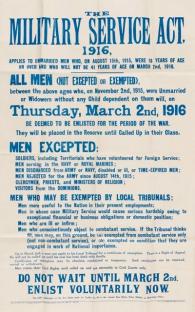

In Britain, despite reservations within the ruling class, Asquith’s Liberal government gradually accepted that no amount of pressure to volunteer could satisfy the war machine’s ravenous appetite for new recruits and proceeded to introduce compulsory military service.[3] In December 1915 Parliament authorised an increase in the army from 2.7 million men to 4 million. By March 1916 the Military Service Act made military service compulsory for single men aged between 18 and 40. In May, during the run-up to the battle of the Somme, a second Act extended this to apply to all men. (There would be yet another in 1918 which raised the upper limit to 51 years of age.) This put paid to the myth that the British army was uniquely made up of volunteers. However, opposition to conscription was a tricky issue for the ruling class as it threatened to go beyond liberal angst about freedom of conscience thus foreshadowing a more collective opposition to the war itself. From the early days of the war compulsory military service had been the bête-noir for a vocal minority of anti-militarists and pacifists, including Liberal party members, Fabians, ILPers (Independent Labour Party, the non-trade union bit of the Labour Party) who otherwise were far from calling on the working class to rise up against the war.[4] In 1916, however, conscription was part of a general stepping up of the British state’s war ‘effort’ to which the working class were increasingly harnessed, whether they liked it or not. And there were signs that many workers involved in armaments and war supplies, particularly engineering workers, were not happy with the constant demand to work longer hours, speed-ups, the de-skilling implied by ‘dilution’ which threatened their wages and the general undermining of the pre-war terms of sale for their labour power.

In early 1915 the TUC’s no-strike agreement with the government had already been undermined by a strike of 10,000 engineers on Clydeside organised by shop stewards outside of the union leadership. Their Central Withdrawal of Labour Committee which negotiated the eventual compromise wage deal was the precursor of the Clyde Workers Committee.[5] The government’s response was more direct state control via the Munitions of War Act which put companies involved in war production under the newly-created Ministry of Munitions headed by Lloyd George. Established trade union practices were suspended and wages, hours, speed-ups and working practices generally were now overseen by the state which became the biggest employer in Britain. In July South Wales miners defied the Act and went on strike for a pay rise to meet the rising cost of living. The government was forced to meet their demands. However, in the same month a Glasgow shop steward from Parkhead Forge was charged with “slacking and causing others to slack” and imprisoned for three months. In ‘Controlled Establishments’ ‘slacking’ was not the only penal offence. It was now a crime for workers to leave their job without the employer’s consent. In practice this was almost impossible to obtain. The Clyde Workers Committee, comprising delegates for thousands of workers from different trades and workplaces, was the upshot of the shop stewards’ attempts to organise resistance against the slave-driving consequences of the Munitions Act. By the summer of 1915, with three hundred or so CWC delegates meeting regularly in Glasgow at the weekend, resistance in the workplaces was growing.

At the same time, the appalling housing situation where landlords were evicting tenants and profiting from the growing housing shortage, sparked a determined rent strike and tenants movement. This melded into mass class struggle when around 15,000 shipyard workers downed tools in solidarity with fellow workers who were being summoned for non-payment of rents. The government was so fearful of the situation that it quickly backed down. Lloyd George (then Minister of Munitions) saw that the court cases were dropped and rent restrictions throughout Britain were quickly endorsed by Act of Parliament.[6] This cave-in over rents was followed by Lloyd George’s famous failure to break the Clyde workers’ resistance to dilution when he toured the area’s factories and met the hostility of 3,000 delegates at St Andrews Hall in Glasgow on Christmas Day 1915.

But for the bellicose British imperialist state it was imperative to remove all obstacles to increasing arms production, including employment of non-time served workers and, even more against the trade union grain, employment of women. Now the government joined directly with the bosses to prepare a further clash over dilution in order to break the Clyde Workers’ Committee and force the workforce to submit to the full consequences of the Munitions Act and thus to being a cog in the military machine.[7]

Conscription Becomes Law

This was the situation in January 1916 when the Military Service Bill came up for debate in parliament and opened the possibility of the struggle against dilution taking on a political dimension against conscription. This, in turn, raised the prospect of wider working class opposition developing against the war itself. The state was very conscious of this danger and was already moving to undermine and suppress it. In this it was aided and abetted by the Labour Party, which on the one hand held a special conference which opposed the Bill, and on the other hand voted not to agitate for its repeal. Its MPs threatened to resign – and then didn’t. The TUC played its now familiar double game: On the one hand it did not object to some local trades councils joining demonstrations against the Bill early in 1916. On the other, it complied with conscription when it was introduced.[8]

Meanwhile, more repressive measures were brought into play. Throughout the land organisers of political meetings against conscription suddenly found their venues had been cancelled. Newspapers were shut down. In January in Glasgow the ILP paper, Forward was temporarily banned for printing an account of the Lloyd George meeting whilst Maclean’s much more anti-capitalist Vanguard, organ of the Scottish BSP, was silenced for the duration of the war. At the beginning of February the Socialist Labour Party[9] press was raided and the machinery smashed up, thus silencing both The Worker, paper of the Clyde Workers’ Committee which was printed by the SLP and edited by an SLPer, John Muir, and – at least temporarily – the SLP’s own publication, The Socialist. This was all part of the state’s two-pronged attack against working class resistance to the sacrifices being demanded for the war: on the one hand to undermine political opposition to conscription and on the other to break the rank and file workers’ opposition to dilution which meant first of all breaking the CWC. First to be arrested were John Muir, Willie Gallacher (chairman of the CWC, member of BSP) and Walter Bell. The next day (8th February) John Maclean was arrested shortly after a public meeting where he addressed a crowd in Bath Street and spoke against conscription and dilution, both of which he clearly saw as part of the capitalist state’s dragooning of workers into a war that was not in their own interest.

We have repeatedly expressed our perfect willingness to let those who benefit by capitalism enter the war, and slaughter one another to their heart’s content. …

It is an entirely different matter when an attempt to force conscription on us is threatened. We socialists, who believe that the only war worth fighting is the class war against robbery and slavery of the workers, do not mean to lay down our lives for British or any other capitalism. If we die we shall die here defending the few rights our forefathers died for. …

So far as mere trade unionists are concerned, we warn them that conscription means the bringing of all young men under the control of the military authorities, whether they be in the field of battle or in the factory and workshop. … Military conscription implies industrial conscription, the most abject form of slavery the world has ever known. …

To the old, as to the young, we appeal for stern opposition to conscription. …

The only way to retain our freedom – the small shred of it we now possess – is by solid combination as a class. The only weapon we can use today is the strike. We urge our comrades to be ready to use that weapon to prevent the coming of absolute chattel slavery.

Do not be paralysed by academic quack socialists, who insist that the only occasion justifying the strike is for the establishment of socialism. These men admit that the masses are still far from socialism. That means we must defer the strike to the remote future. See how absurd the position is, and act accordingly.[10]

In fact around 10,000 workers did go on strike in protest at these arrests. While the CWC men were allowed out on bail, the ‘authorities’ made sure Maclean was silenced. He was quickly taken off to Edinburgh to await trial on six charges of sedition which in April would bring him a 3 year prison sentence. Meanwhile the state’s plan to divide and break the CWC went ahead. In the same week as these arrests David Kirkwood, the works convenor and at that time still an SLP member (he later joined the ILP) had signed a unilateral agreement with the dilution commissioners for Beardmore’s Parkhead Forge workers. This further undermined the unity and determination of the CWC. When the management at Parkhead provoked a strike by limiting Kirkwood to his own workshop, the end was nigh. Solidarity action was not as strong as usual because of Kirkwood’s sell-out over dilution. Of the sympathy strikes that did occur, eight CWC leaders, including Kirkwood, were arrested and deported. Posters appeared threatening strikers with prosecution under DORA and the Munitions Act. As the government and bosses had calculated, and as John Maclean had suspected, the remaining CWC leaders balked at calling what would be interpreted as a political strike against the war with all the punitive repercussions that would imply. Thus the CWC was broken and for the time being the prospect of wider working class resistance developing to both industrial and military conscription and thence the war itself was undermined. This is a historical fact and in itself is not the key issue for today.

Yet for anyone today who wants to see a revived working class struggle taking on revolutionary dimensions, it is instructive to study the role of the political organisations and figures involved. On the one hand, the SLP’s peculiar mix of revolutionary Marxism and rank and file unionism in practice came to emphasise the latter and, if William Paul’s work is anything to go by, since the Party’s vision of socialism was basically a picture of workers taking control over industry, this conveniently sidelined the need to overthrow the capitalist state which would simply be by-passed and prove itself unnecessary. And although the SLP in practice had to face up to state repression and adopt illegal strategies to carry on political work this strand of blinkered, workshop rank and filism became the political Achilles heel of the SLP even as it allowed the organisation to win support in workplaces, amongst engineering workers in particular. On the other hand, John Maclean, despite the wide political support he had amongst workers in Glasgow and Lanarkshire, saw no need to make a clear break with the BSP and social democracy, preferring instead to set up his ‘own’ Scottish paper The Vanguard, and leaving the English sections to do the work of political clarification needed to oust Hyndman and his jingoistic followers from the organisation. Part of this process involved setting up a new paper, The Call, in February 1916 around the time Maclean was arrested. Maclean did write for The Call after he was released from prison in 1917. Meanwhile though, the voice of the revolutionary, “fighting dominie [school teacher]” was silenced while Hyndman and co. were finally expelled from the BSP at the Party’s Easter conference, April 23rd-24th, 1916.

Despite the increasing hold of the state which was doing all it could to nourish the atmosphere of intolerant nationalism amongst the whole population, the hard material facts of the war were feeding dissent. On the political front, for example, Sylvia Pankhurst who was actively speaking out against conscription, marked a shift from “votes for women” to focus on the working class as a whole when she renamed the East London Federation of Suffragettes the Workers' Suffrage Federation (WSF) in March 1916. The Women’s Dreadnought newspaper was in turn renamed the Workers' Dreadnought. It was not yet the newspaper which was ready to call for working class revolution but it did campaign against the introduction of conscription. It played a key part in organising working class anti-war demonstrations (albeit in terms of the demand for peace), notably the demonstration in Trafalgar Square, again over the Easter weekend of 1916. On the economic front, the ever-increasing cost of living was only offset by the growing number of female family members going out to work and the generally higher number of hours worked per week. Even so,

In the summer of 1916 there were several important protests and demonstrations against the high cost of living, including one organised by the National Union of Railwaymen and held in Hyde Park on 27 August.[11]

Up Against the State

Even so, the overriding atmosphere was one of nationalism and intolerance where thousands were interned in camps under the Aliens Restriction Act (1914), giving implicit state sanction to thuggish acts of ignorant bigotry. The Trafalgar Square demonstration for example was broken up by so-called patriots, encouraged by the Northcliffe and Beaverbrook press. (Times, Daily Mail and Daily Express)[12]. As for conscription, whilst a concession was made in the Military Service Act to the anti-militarist/freedom of conscience lobby by granting the possibility of individual exemption on the ground of “a conscientious objection to the undertaking of combatant service”, it was the same tribunals who were already pronouncing (under the Derby Scheme) on whether or not someone had practical grounds to be exempt from military service who judged these cases. Unsurprisingly, such tribunals refused exemption to most of the men who came before them. In the first six months of the Act over 750,000 cases were heard but from March 1916 until the end of the war there were only 16,000 or so registered conscientious objectors. Most of them accepted alternative service but a thousand or so held out for absolute exemption and refused to recognise the military authority they were put under. This gave the Army, especially in the early days, free run to practice mock executions, torture and any number of humiliating and degrading treatments. Over the course of the World War One commemorations there has been substantial reporting on the brutal treatment of conscientious objectors but little recognition of the fact that,

Numerically, the larger part of the ultimate resistance came from Socialists. Some took the humanitarian stand-point, not in essentials different from the Christian objection; others were mainly out against Capitalism. Many advocated a Socialist philosophy based upon a new conception of the relation of the State to the individual citizen. Some would not help militarism which was the means of exploitation. Some of these would have been willing to take up arms in a violent revolution, others declined any such methods anywhere.[13]

One of these young socialists was nineteen year old Percy Goldsborough from Mirfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire who, in words echoing John Maclean, wrote on the wall of his prison cell in Richmond Castle:

The only war which is worth fighting is the class war. The working class of this country have no quarrel with the working class of Germany or any other country. Socialism stands for Internationalism. If the workers of all countries united and refused to fight there would be no war.

We do not know what Goldsborough thought of the Second International’s betrayal of internationalism or whether he would have agreed with Lenin that,

Our slogan must be: arming of the proletariat to defeat, expropriate and disarm the bourgeoisie. These are the only tactics possible for a revolutionary class, tactics that follow logically

from, and are dictated by, the whole objective development of capitalist militarism. Only after the proletariat has disarmed the bourgeoisie will it be able, without betraying its world-historic mission, to consign all armaments to the scrap-heap …[14]

All we do know is socialists in Britain were largely cut off from the Zimmerwald movement as a whole and in particular from the Zimmerwald Left[15] which was not only aiming for the creation of a new, revolutionary International but trying to work for that revolution to come about. This is a far cry from the spirit of today’s centenary celebrations such as the anniversary of the first march of the Women’s Peace Crusade which took place in Glasgow on 23 July 1916, but which absolutely fail to acknowledge that it was revolution that put an end to a war which did not end all capitalist wars.

As it was, 1916 was drawing to a close with the working class in Britain increasingly pressed into more sacrifices for the war machine. At Verdun, the world’s longest battle which lasted from 21st February-18th December, 1916 of the two million men who fought, half had been killed. Battle lines remained the same as at the beginning. On the Somme, in the 4 months from 1 July 1916 over 1 million men died. The British dead stood at 95,675 – 20,000 of them on the first day of the battle. The French lost 50,729, the Germans 164,055. Over 60% of the Australian troops who fought were killed. When the battle ended in November “the British line had moved forward six miles, but was still three miles short of Bapaume, the first day’s objective”.[16]

By the end of 1916, there were signs of war weariness amongst the working class on both the military and the home front accompanied by sharpening tensions as the government and the army clamped down more severely on anything that might provoke a more general resistance. In the autumn the British army had passed its first death sentences on seven soldiers explicitly for mutiny. (That is, as opposed to death sentences for desertion and cowardice). On the western front it was now standard practice for an officer to shoot one of the soldiers in order to get the rest to move out of the trench.[17] On the home front, dilution proceeded in the munitions works with more and more women being taken on to replace men who were ‘released’ for military service.[18] Men who thought they worked in ‘protected’ industries and were therefore immune to military service found themselves being called up by the army. The engineering workers’ strike over the call up of Leonard Hargreaves, which signalled the revival of the shop stewards’ movement in Sheffield in November 1916, was not in itself a protest against the war. It was a demand for the unions (in particular the Amalgamated Society of Engineers) to be given control of who should or should not be sent into the army, a demand that was conceded by the government through the trade card scheme. As such it was a concession fully in keeping with the proto-fascists belonging to right-wing ‘patriot’ gangs such as the British Workers National League (who demanded that the war be continued to a victorious conclusion and key industries taken into public ownership), supported by various unions like the National Union of Dock Labourers, or the National Amalgamated Seamen’s and Firemen’s Union and union leaders such as Ben Tillet and Ernest Bevin.[19] The trade card scheme negotiated by the Sheffield shop stewards was a far cry from the Bolshevik workers in Petrograd who were refusing to participate in the war industry committees[20].

The working class in today’s crumbling capitalist world is being enticed by all kinds of reactionary political agendas. This brief overview of how things stood in 1916 in Britain can only remind us that, unless we have a clear understanding that a new world is possible and have a clear political perspective about how to get there, nothing will stop the forces of capitalist barbarism.

E Rayner

13.11.16

Glossary

BSP = British Socialist Party. Founded 1911 it was split between pro and anti war factions and only with the victory of the latter did it become a revolutionary party and constituent part of the Communist Party of Great Britain after the war.

SLP = Socialist Labour Party. Founded in 1903 by the left wing of the Social Democratic Federation from which it split by James Connolly and Neil Mclean. Influenced by the ideas of the American socialist Daniel De Leon. It split in 1920 when most of its leading figures decided to abandon opposition to affiliating with the Labour Party as a condition for joining the newly-formed Communist Party

Notes

[1] Our other articles on the First World War:

August 1914: When Social Democracy Went to War

Social Democracy, the First World War and the Working Class in Britain

Their First World War Commemorations and Ours

May 1915: Italian Entry into World War One and Internationalist Opposition

Zimmerwald: Lenin Leads the Struggle of the Revolutionary Left for a New International

Class War on the Homes Front, the Glasgow Rent Strikes of 1915 (published in Aurora 33)

Harry Patch: The Last Fighting Tommy

Thy can all be found at leftcom.org. Just follow the links.

[2] The phrase comes from a book, The War That Will End War, by the then Fabian, H G Wells. Based on a series of pro-war articles he wrote in 1914, he basically blamed ‘the other side’ for the war and argued that the defeat of German militarism would bring an end to warfare in general. This is already the vastest war in history. It is a war not of nations, but of mankind. … It aims at a settlement that shall stop this sort of thing for ever. Every soldier who fights against Germany now is a crusader against war. This, the greatest of all wars, is not just another war—it is the last war! Available to read online at: archive.org

[3] By the end of January 1916 the UK casualty rate on the Western front alone had reached over 403,000 which means that roughly one out of every seven soldiers in the army as a whole was out of combat. [Based on figures of Western front casualties from historum.com]

[4] Even if Keir Hardie had been a staunch supporter of the 2nd International’s pre-war resolutions for an international general strike against a European war should it break out, his anti-war stance like the vast majority of Euopean leaders of Social Democracy evaporated once war was declared. In December, 1914 ILPers had joined with Liberals to form the Union of Democratic Control which was opposed to conscription and infringement of civil liberties. The UDC was for a negotiated peace via open diplomacy on the part of the British government but did not propose an immediate halt to the war or otherwise impede its prosecution. In the same month Fenner Brockway, a pacifist and editor of the ILP paper, the Labour Leader, started the No Conscription Fellowship which played a key role in campaigning for and supporting conscientious objectors throughout the war. He himself was imprisoned three times and finally released in 1919.

[5] Although the strike was organised outside and against the main engineering union (ASE) which had refused to hold a ballot, it started over a typical trade union issue: the employment of new workers at a higher rate of pay, in this case American engineers who had been taken on at Weir’s of Cathcart. At its height 10,000 or so engineers from twenty-six factories were on all-out strike for a 2d per hour pay increase. In the end the union executive stepped in to patch up a deal for a 1d per hour wage rise and 10% on piece rates and the engineers went back to their 54 hour working week (dayshift) and 60 hour week (nights), before overtime. Arthur Marwick remarks, “[it] reveals much about the working class on Clydeside, always in the final analysis touched by a near and real issue rather than any hypothesis about the final collapse of capitalism.” See The Deluge, 2nd ed. p.112.

[6] For more on the 1915 rent strikes in Glasgow see Class War on the Homes Front, first published in Aurora 33, and available on our website at leftcom.org

[7] See Chapter 4 of James Hinton’s The First Shop Stewards’ Movement, [George Allen and Unwin, 1973] for evidence from official correspondence of a deliberate plan to break the CWC, starting in November 1915 with a quotation from a letter in the Beveridge collection viz: “To obtain a reasonably smooth working of the Munitions Act, this committee should be smashed.” Also in Iain McLean’s DPhil. thesis: The Labour Movement In Clydeside Politics, 1914-1922, who notes that this is from a letter by the Admiralty’s Captain Superintendent on the Clyde in response to the CWC’s manifesto, To All Clyde Workers. Available as pdf at: ora.ox.ac.uk:443

[8] Ken Weller notes that although “By November 1915, Islington Trades and Labour Party had reversed its decision to support recruiting. This in turn led to the resignation or dropping out of many of the pro-War faction, although it did not stop some of them having long and successful careers in the labour movement. Apart from its decision not to support recruiting I can find no evidence of the Trades and Labour Party playing any part in the anti-War movement.” Ken Weller, ‘Don’t Be a Soldier’, posted on libcom.org

[9] Founded in 1903 by a split from the Social Democratic Federation, the SLP drew its political positions from a peculiar mixture of Marxism and industrial unionism. With a strong presence amongst the industrial working class on the Clyde it was the principal political force inside the CWC.

[10] Not from a speech, but an article entitled ‘The Conscription Menace’ published in The Vanguard, December 1915. See p.88 In the Rapids of Revolution, collection of some of John Maclean’s writings edited by his daughter, Nan Milton; pub. Alison and Busby 1978.

[11] Arthur Marwick, The Deluge Macmillan 1991 p.166.

[12] This is a record of how two young men at the time saw it: “Me and Evan are still waiting for letters telling us when our tribunals are. If they’re so keen to get us out to fight, you’d think they’d get a move on with it. Still, I suppose it takes a while to sort out when they’re still working through all the fuss and bother from the Derby Scheme. Went to a peace meeting in Trafalgar Square today. We always go along with great ideas but it ends up in a mess every time. Today we thought we’d have a better shot at keeping the peace, what with having Miss Sylvia Pankhurst there supporting us, but the moment the crowd caught hold of what we were doing they started ripping down our banners and turning on any of us who tried to stop them. I did well not to come away with another bust nose. Evan says they can’t help it, it’s just what the newspapers are making them believe, but you can’t help getting angry when they’re hell-bent on breaking up a peaceful protest. The other day the Daily Express called us “neurotic curiosities” though, so it’s no wonder, is it?” From: ww1soldierstale.co.uk

[13] From ‘Conscription and Conscience, A history 1916-1919’, p. 35 John W. Graham, M.A (Principal of Dalton Hall, University of Manchester, Author of ‘The Faith of a Quaker’.)

[14] V.I. Lenin, The ‘Disarmament’ Slogan, October 1916 – p.96, Vol. 23 of Collected Works (Progress Publishers).

[15] The revolutionary minority amongst the Zimmerwald movement, who realised the 2nd International had sold out the working class by support for the war and aimed for the creation of a new International.

[16] Martin Gilbert, The First World War, 1995 p.299.

[17] Martin Gilbert, The First World War, 1995 p.299.

[18] See again, for example ww1soldierstale.co.uk which describes the “weeding out" of single men from the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, for military service has begun on a considerable scale, large numbers of war service certificates entitling them to exemption having been cancelled during the past week. It is understood that thousands of Lancashire girls and women accustomed to machinery are to be brought to Woolwich to take their places. So difficult is the problem of housing the newcomers that all appeal has been issued asking all who can accommodate them to communicate with the manager of the Woolwich Labour Exchange.” 29.4.16

[19] For more on the BWNL and the role of particularly reactionary unions, see Brock Millman, ‘Managing Domestic Dissent in First World War Britain’, p.113ff. Frank Cass, 2000.

[20] See our pamphlet 1917 at leftcom.org

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

Many thanks to E.Rayner for such an historically informative article. However, it reminds me of many conflicting strands of thought. For instance, wearing the badge of the War Resisters International, when a teenager at school in the early fifties, caused a teacher to comment that that was not much good when someone was pointing a rifle at you ! But the subject of pacifism needs to be re-examined when considering the following. A pacifist might accept being personally killed rather than acting as a killer, but if he or she were a parent, and if any sort of enemy threatened to take or wound or kill his or her children, would it better to become a killer of the enemy rather than not do so ? The same sort of argument, magnified, can be viewed as for the working class and, yes, the nations in which workers happen to live. Whilst taking on board all the arguments about imperialism generating wars for all its reasons, and whilst also acknowledging that World War 2 was not fought specifically against the holocaust, once the war was unleashed and persisted, it became apparent, at least by by 1945, that if Churchill and Stalin had not combined in their leadership to defeat the nazi regime (a product of capitalist crisis of course), then just standing back would have been even more of a disaster than the war itself. Today it remains true that imperialism has all the factors in itself to produce wars, but especially important is the need for big firms, such as the US and other arms industries, to make big profits. Weapons, except for I.E.Ds, are not being manufactured in tents in the desert. Sometimes it is tempting to go to the Buddha for refuge, but does that end suffering ?!

We encourage armed workers not to lay down their arms but to turn imperialist or so called national liberation wars into wars against capitalism.

As stevein said, the subject is not pacifism: a pacifist will never threaten capitalism. Once we see that world wars are the ultimate expression of the inbuilt crisis of the mode of production then really the only war worth fighting is against the system itself because there is nothing progressive to fight for. In WW 2 neither side had the monopoly on barbarism.

True enough, arms production becomes more important to capital as other areas of profitability dry up. But we can’t expect arms workers to support demands for the shutdown of their workplaces, just as the working class in general is not moved by idealist demands and campaigns to reform capitalism.

Elsie Rayner

I must stop commenting on CWO articles, because I must grapple daily with survival from age 80.5 onwards, whilst the proletariat will get on with whatever it sees appropriate.