You are here

Home ›Ragged Trousered Philanthropists

A Rare Night Out in Richmond!

A review of a performance of Louise Townsend’s production of the two-handed version of the 1978 stage play by Stephen Lowe based on Robert Tressell’s novel on tour.

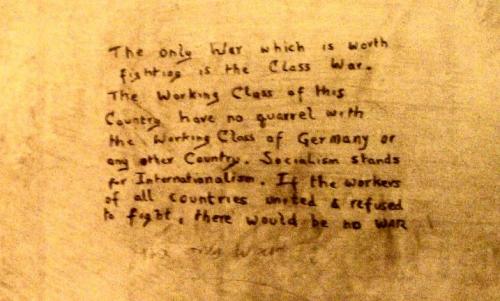

The Georgian Theatre Royal, Richmond, Yorkshire was not the first choice venue to see this play but having been on holiday when it was at the Darlington Arts Centre (now closed due to the cuts) this was a last chance (at double the cost!) as the tour came back from its triumph at the Edinburgh Festival. Surrounded by army bases (Catterick is a couple of miles away) and one of the safest Tory seats in the UK (current incumbent, the Foreign Secretary) with a castle which housed revolutionary defeatist opponents of the First World War[1] neither Richmond’s past, nor its present, suggest a welcome for socialist theatre.

But the tiny Georgian Theatre (seating for about 200, with no-one more than 10 metres from the stage) lent itself to the brilliant Brechtian performance of the two actors, Fine Time Fontayne and Neil Gore. The old theatre did have one early drawback in that the stage was so small bits of the scenery kept getting knocked over. However this all added to the fun as our two actors ad-libbed around every minor disaster (including Fine Time missing some lines at one point). It was actually difficult to know when the performance actually began as Fine Time wandered out to talk to members of the audience beforehand and the banter that ensued just drew us into the action before we knew it. I had a suspicion that “the cast” were really quite nervous about the reception they might get in Richmond. At first sight the audience of around 150 was not promising, made up overwhelmingly of what I guessed were retired professionals (certainly with a lot of posh accents) although there was one young man sitting up in “the gods” who I noticed earlier had arrived on a bicycle: Highly suitable for an Edwardian evening.

And Edwardian evening was what we got. It does not seem credible that two men could play so many roles (previous reviewers all give different numbers as to how many so I won’t try) but using swopped voices, dress, and especially hats, they pull off the trick convincingly. The performance had just about everything in a sort of cross between Bertholt Brecht and old time music hall. Songs abounded accompanied by accordion, banjo and ukulele. The audience was engaged throughout whether through collectively singing along (harmoniously to my ears) to “Two Lovely Black Eyes” or clapping rhythmically to the treadmill of the famous “Money Trick” where two “volunteers” were dragged up to play “workers” being exploited by Fine Time’s “capitalist”, a character we were encouraged to boo lustily. The many arch asides to the contemporary crisis were not lost on the audience either. Anti-capitalism it seems has now become respectable – but more of that later.

The main theme of the play is the autobiographical story of Frank Owen (Robert Noonan aka Tressell) who is a socialist despairing of the ignorance of his fellow workers who are the “philanthropists” of the title since they donate the product of their labour to the capitalists for a pittance in return. The main scene is “The Cave” a huge house being prepared for the Mayor (“Alderman Sweater”) where Owen and his pals are working for starvation wages for the building and decorating firm of Rushton and Co. Set in Hastings in the early 1900s, trade is depressed and the firm’s foreman Hunter is obsessed with cutting costs. This means not only in doing a shoddy job with inferior materials but above all wages. If he can replace the 7d an hour men with 6 and half pence an hour (or less) men he will be in ecstasy.

It is in this context that Tressell’s famous scene where Owen presents “the money trick” to his fellow workers to demonstrate with slices of bread and three knives how they create all the wealth (surplus value in Marxist terms) which is then appropriated by those who own the means of production (raw materials or bread and means of production or knives). The men are paid for what they produce but have to immediately hand the money back to the capitalist who gives them a mouthful of bread (“the necessities of life”) from the pile which they have produced. Once they have eaten it they have to go back to work for him again to repeat the process which ends with a huge accumulation of cut bread on the capitalist’s side and precisely nothing on theirs. The creation of surplus value and the basis of exploitation explained in a nutshell. It was brilliantly done and brought a huge ovation which gave way to loud approval when the two “volunteers” plucked from the audience were presented with free copies of Tressell’s book for their pains.

The centrepiece of the whole thing is the “Beano”, the annual treat for the workers supplied by Rushton and Co. Rushton is played by Neil Gore with such an insinuating whine that you want to throttle him. Rushton makes a speech to the, by now largely drunk, men pointing out that the division of labour between his brain and their brawn is what makes the world work well. The men all cheer but the class war is really kicked off by Mayor Sweater who praises Rushton’s speech and begins an attack on “socialists”. The men jeer Owen and his pals and egg them to reply. Owen is struck by a fit of coughing (something which he does with increasing frequency throughout the action to remind us that the disease of the poor, TB, was consuming Tressell as he wrote) so Harlow jumps up and replies for the socialists with an effective denunciation of the boss class. After this we are back to music hall. Crass, the chargehand, drunkenly tells us about “this French chap”[2] who can fart the Marseillaise and drops his trousers to offer us “God Save the King” in the same vein. His further threat to drop his grimy underpants was met with a loud “no” from certain sections of the audience (this was Richmond after all). We were spared the performance of this “fartiste” by the arrival of the dignitaries.

The music hall motifs though continue with the toffs all satirised in a Punch and Judy show which quote more modern Tories (Thatcher included, of course). I don’t know whether it was intended but this music hall agitprop contained its own sort of irony. The music hall was in those days before a mass media the main means for imperialist indoctrination. The word “jingoism” itself comes from a music hall song of the late nineteenth century.

The mickey-taking of contemporary Tories in the Punch and Judy show was the only time we noticed a frisson of cold water douse the anti-capitalist enthusiasm of our audience. And this brings us to the consideration of the show as both art and agit prop. On the level of pure entertainment people will have to go a long way to experience such an enjoyable evening.

But in the end all art is ambiguous and it is clear that everyone can take away their own message about its significance. The play finishes with the Owen (who is now largely unemployed and clearly dying) and Harlow hoisting Owen’s unfinished banner. It looks like a trades’ union banner but has only a picture of the globe with two hands grasped across it and the words “Workers Unite” on it. The final words of the play are “Brothers, sisters, (long pause by Neil Gore) … comrades!”. As the play is sponsored by the GMB, RMT, PCS, UCATT, the NASUWT and the TUC Cymru it is clear that the unions take from it the message that it is all about workers banding together to prevent wage cutting. But Owen is a “socialist”[3] and not a Labour man at that. When he hears that his friends have decided to participate in elections he objects that this is playing the bosses’ game and we cannot win that way. For him the solution is not in getting “crumbs” from the capitalists but in getting rid of the system of exploitation. The trades unions live in that system and for that system, as they exist only to negotiate for “the crumbs”. They want a capitalism that is “fair”. In fact what united the audience (even in well-heeled Richmond) was the idea that, then and now, capitalism is manifestly “unfair”. The problem is that a “fair” capitalism is an oxymoron. Owen did not want to reform capitalism but to end it. The unions and other purveyors of reform are not even close to Owen’s programme or his vision.

There is a review of the show from The Times by Libby Purves on the website of Townsend Productions. It is a good review but in it she takes to task the leader of the Unite union for insisting that “the game has not changed much since 1914”. She points to the welfare state, the minimum wage and tribunals to contradict this. These, of course were won by workers in struggle in the past but, such as they are, they are being once again being eroded by the inexorable capitalist crisis. Workers are once again being asked to pay for the contradictions of a fundamentally irrational system. Howard Brenton, who wrote an earlier stage adaptation of the Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, put it better. The story still appeals because “everything is different but nothing has changed”. By putting the nature of exploitation at the heart of this production Fine Time Fontayne, Neil Gore and Louise Townsend made this feel like a real critique of where we are now. Frank Owen lives. The tour goes on until November[4]. Go see it

Jock

[1] The picture at the top of this review is a reproduction of graffiti from the cell block in Richmond Castle. This is now closed to the public so we cannot identify the writer but he is probably one of two brothers called Law.

[2] Joseph Pujol did actually perform on the French stage as “Le Petomane” for thirty or so years before the First World War. He did not actually fart. He had a deformity of the anal sphincter which allowed him to draw in air and then musically release it. Ironically he was so traumatised by the First World War that he gave up performing altogether.

[3] Robert Noonan joined the Social Democratic Federation, many of whose member found their way via the British Socialist Party into the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain in 1921. Noonan himself died in 1911 (Presumably the current play, which started in Hertford last July, is a commemoration of the centenary his death). His novel was published with all references to socialism deleted in 1914 and the first unabridged version appeared in the 1950s.

[4] See townsendproductions.org.uk

Although it is on in Harrogate in February 2013. Perhaps it might then go on a tour of CIU clubs or the like to try to reach the audience Tressell had in mind?

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

Good write up.

"Crass, the chargehand, drunkenly tells us about “this French chap”[2] who can fart the Marseillaise and drops his trousers to offer us “God Save the King” in the same vein. His further threat to drop his grimy underpants was met with a loud “no” from certain sections of the audience (this was Richmond after all). We were spared the performance of this “fartiste” by the arrival of the dignitaries.

The music hall motifs though continue with the toffs all satirised in a Punch and Judy show which quote more modern Tories (Thatcher included, of course)."

As a youth one of my favoutite bands was CRASS and funnily enough the lead singer, Steve, ended up doing Punch and Judy shows.