You are here

Home ›Capitalism's Economic Foundations (Part V)

Globalisation and its Discontents

Before continuing with this section which brings us closer to our contemporary world, it is worth summarising the key elements in this necessarily truncated analysis of almost fifty years of capitalism’s profitability crisis. Indeed, it is worth explaining first of all, why we hold to the term ‘crisis’ to describe a period of almost five decades. The simple response is that, despite the undeniable fact that capitalism survived the first great economic crisis that put an end to the post-war boom and has gone on to further entrench itself in what were once peripheral areas of the world economy, the problem of diminishing returns on capital invested in the production of new value remains, and indeed is worse today. With the notable exception of Paul Mattick, in the 1970s and ‘80s, the majority of academic Marxists wittingly or otherwise, based themselves on Rosa Luxemburg’s saturated markets theory to equate the crisis of capitalism with capitalist ‘imperialism’ defined simply as the decline of pre-capitalist markets. In recent decades, a number of more or less academic scholars have returned to Marx and the labour theory of value and provided us with ample evidence to confirm the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, both in monetary and (approximate) value terms.(1)

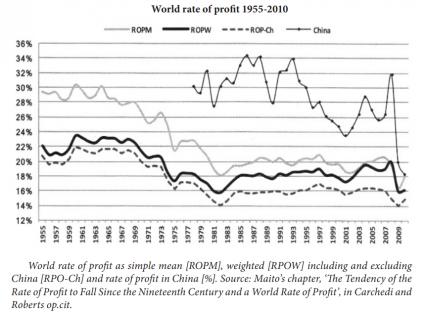

Their calculations generally confirm the tendency for the rate of profit to fall, in both the richest ‘core’ countries and peripheral economies and this is reflected in Esteban Ezequiel Maito’s graph illustrating the fall in the global rate of profit below.(2) Though the calculations appear precise enough, it is worth noting they are based on data from only fourteen countries. More worryingly, “given the difficulty of calculating the constant and variable circulating capital” (p.137), instead of using Marx’s formula of s/c + v, Maito’s calculations are based on “the rate of return on fixed constant capital” (s/c) which he argues “tends to converge with the Marxian rate of profit in the long run”. In terms of the graph here, he points out that the weighted rate of profit in bold reflects the “return on total social capital” and is thus closer to Marx’s rate. Clearly we are dealing with approximations. In any case Maito’s calculations in the graph below are roughly borne out by others. More fundamentally, however, it is worth noting that Andrew Kliman’s equivalent graph for the US rate of profit, based on calculations which do take account of wages, describes a much lower rate of profit.(3) For our purpose we can simply note that they all confirm the same post-war trend of a general decline in the post-war profit rate which, despite subsequent dips and recoveries, has never regained its post-war highs.

Maito, a là Henryk Grossman, has even calculated how long it will take before the fall in the rate of profit becomes a fall in actual profits and eventually no profit at all and thus the collapse of capitalism, “which now seems to remain fixed to the middle of this century”.(4) To give him his due, he does acknowledge that the “move towards the ‘end point’ should be understood … as a particular historical period that poses significant challenges for the working class.” It is one thing to acknowledge the inherent transience of capitalism, it is another to translate this into historical and political context and, above all, recognise the significance of the capitalist mode of production continuing to dominate the whole globe. As we explained in part two of this series, competition is no longer a purely economic battle between firms but imperialist rivalry between ‘great powers’; where, in short, the massive devaluation of capital required to assuage the crisis of low profitability and achieve a new round of accumulation is achieved by the destruction of capital values via war. Capitalism itself developed within feudal society but — potential world war, global warming and wider environmental damage notwithstanding — contemporary capitalism is not nurturing an alternative mode of production within its crumbling frame even if its existence depends on the continued appropriation of new value created by the “collective producer class” whose labour is the basis of all capitalism’s wealth. The decline of capitalism does not mechanically lead to communism. It is a reformist illusion to anticipate a natural ‘winding down’ of the capitalist mode of production while the working class gradually builds up ‘oases’ of socialism in the old society. In fact the opposite is the case. Capitalism still has to be challenged politically and the majority of the working class will need to become involved in creating the organs of working class democracy, ranging from the local to global, that will accompany the revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist state by the proletariat and the immediate turn towards production to directly meet human needs.

The last fifty years of unresolved economic crisis have shown that ‘revolutionary action’ is not a natural outcome of capitalist decadence. While there have been significant class battles, especially during the first two decades, the period has been defined above all by extensive write-offs and restructuring of capital at the expense of the working class. The collapse of the Russian bloc was not simply a political triumph for ‘free market capitalism’. It entailed a massive devaluation of capital (unprecedented outside of war) as whole sectors of industry were shut down leaving the working class facing unemployment, without the means to live and embroiled in a disastrous struggle to survive. In the Western bloc too unemployment shot up in the mid-1970s and '80s following wholesale write-offs of unprofitable enterprises and abandonment of once key national security industries associated with the 'Industrial North' in the UK and the 'Rust Belt' in the USA.

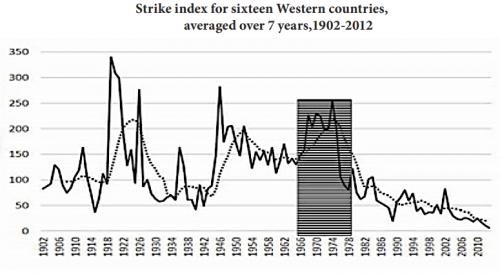

The effects of the capitalist crisis and restructuring did meet resistance from workers. The number of strikes during the 1970s mounted to a post-war high. But if it is true that the intensity of the class struggle inspired a revival of revolutionary political groups, their influence on the wider class struggle was minimal while redundancy payments and state support for the unemployed in the main secured ‘social peace’.

Thus the working class was decimated and the ground prepared for a revival of accumulation, albeit at a lower rate of profit, and in the changed context of fewer barriers to global trade, where China, with its vastly cheaper labour force, attracted investment from the West (indeed, no less than a third of all global foreign investment) and took on the role of workshop of the world, particularly in consumer goods. At the same time the productivity rate of what remained of the manufacturing/industrial workforce in the old capitalist ‘heartlands’ increased with the introduction of new technology, primarily based on the microchip.

But while the volume of manufactured goods has increased the portion of the world’s workers engaged in manufacturing has declined.

According to McKinsey(5), between 1996 and 2006 there was a 24% decline in the number of global manufacturing workers while they contributed 20% of the new ‘value added’ to a world economy where manufacturing accounted for approximately 16% of global GDP and 14% of employment. Since then (up until 2021), according to the UN, employment in manufacturing has remained around 14%.(6)

The World Bank’s calculations, based on the overall global workforce in 2021, i.e. including those unemployed and not just the number of people in paid employment, is even lower. Out of a global workforce of 3.5bn it reckons manufacturing jobs as % of world employment = just over 11% (11.025%).(7) The ILO’s figures are higher: “the share of employment in the industry sector has remained stable throughout this period, at 22%”.(8) The mismatch between the two employment figures is probably due to the fact that the ILO includes mining, forestry and so on in the ‘manufacturing’ category.

In any case, the picture is clear: the portion of the global workforce who produce new value has declined. Incidentally the share of employment in agriculture has also decreased, from 44% to 27%. Meanwhile, again according to the ILO for the same period, “the share of service jobs in all global employment has increased ... from 34% in 1991 to 51% in 2019”. While not all service work is devoid of producing a certain level of surplus value,(9) the vast bulk does not, including the world’s burgeoning financial sphere. The fact is that capitalist accumulation depends for the most part on the surplus value extorted from workers involved in the production of manufactured goods, including the extraction of raw materials.

By contrast, the ‘financial services sector’ produces no new value and although banks, brokers and investment advisers no doubt still serve a useful function in the garnering of surplus value for investment in a new round of accumulation, this ‘service’ comes at the price of a financial rake-off (interest) from expected profits. In short, the vast panoply of ‘financial services’ from banking, investing (including stock broking and derivative trading), real estate, insurance, accounting, to ‘debt resolution’ and credit payment ‘providers’ (the likes of Visa or PayPal): they are all a drain on the new value produced in any given round of the capital accumulation process. Of course, this is not how the of the representatives of the financial services industry describe their role. Let’s allow one of them to present their case.

The financial services industry is worth $20.49 trillion worldwide. This was true as of 2020, and it was estimated that the industry would reach $22.52 trillion in value in 2021.

If these numbers sound massive, they are because this sector makes up approximately 20-25% of the global economy as a whole. It’s hard to nail down an exact percentage, but most experts agree that financial services account for about one-fifth to one-quarter of the world’s economy.

The industry is only expected to continue growing at a CAGR [compound annual growth rate, CWO] of 6% from 2020 to 2025, reaching $28.53 trillion in value at the end of that time period. ...

Western Europe accounts for the largest share of the global financial services market at 40%.

North America comes in second place, making up 27% of the world’s financial services market.

The market capitalization of the global banking sector is €7.5 trillion as of Q3 2021.

Meanwhile, despite the interruption of the Covid lockdowns, “The number of Americans employed by the U.S. financial industry grew from 6.09 million in 2016 to 6.55 million in 2022.” (10)

What’s not to like about this miraculous ability of financial services to conjure up more money from money (M-M1) simply by buying and selling “promissory notes which were issued for a capital originally borrowed but long since spent … paper duplicates of annihilated capital”(11) ad infinitum, without the need for any effort from the owners of the certificates (whether actual or virtual, they are all a fiction).

With the blossoming of an inter-continental ‘financial services’ sector since the early days of capitalism’s crisis in the 1970s the frequency, intensity and scope of financial crashes has increased. Here we must mention three of the most significant prior to the great global financial crash of 2007/8. The first is the deflating of Japan’s stock market bubble which occurred between 1986 and 1992, largely a consequence of speculation in real estate, itself a consequence of a low rate of profit on capital invested in manufacturing. Not only was the eventual Nikkei crash the biggest in post-war history, Japanese stocks never regained anywhere near their previous values (and fell even more dramatically after the great global crash). The once pace making economy stagnated despite the Bank of Japan implementing a 0% interest rate policy from the late 1990s until very recently.

The second notable crash occurred on Monday 19 October 1987 and is remembered as Black Monday — the day when a 20% or so drop in Standard & Poor’s 500 Index and the Dow Jones Industrial Average in the United States triggered a plunge in world markets which lost them the previous year’s gains more or less overnight. However, it is not the losses that are of significance. It is the reaction of the US Federal Reserve which, under Republican appointee, Alan Greenspan, delivered its first public promise of support for financial markets, proceeded to cut interest rates and called upon banks to flood the system with liquidity. Over the next decade the Fed continued with its constant stimulus project, including interest rate cuts to aid recovery.

The third sign of things to come was the bursting of what came to be known as the dot.com bubble: the spectacular crash of the New York based NASDAQ stock exchange dealing mainly in internet company shares which lost 95% of their nominal value when the bubble burst in September 2002. Inevitably bankruptcies ensued and the US economy went into recession.

Overall, the financial consequence of these stock market explosions was a net loss of more than $2.5 trillion. Then came the big one: the so-called ‘subprime mortgage crisis’, the biggest financial crash so far in capitalism’s history that was triggered by the first run on a British bank in 150 years. The repercussions of this worldwide crash extended far beyond the financial domain and way beyond mortgages and housing. The US itself entered a deep recession, with nearly 9 million jobs lost during 2008 and 2009, roughly 6% of the workforce. The plight of homeless people sleeping on the streets was one of the triggers of the ‘Occupy’ movement, an amorphous political protest movement of ‘tent cities’ in and beyond the United States. Meanwhile, the US’s ‘stand on your own feet’ approach to manufacturing industry gave way to a state $25bn bailout for General Motors: still only a tiny fraction of the $1.7+ trillion doled out to the likes of Bear Stearns, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, Citi Group, AIG, Bank of America and TARP (the Troubled Asset Relief Programme).

Europe also felt the effects with a slowdown in industrial production, increased unemployment and banking losses running to an estimated €940 billion between 2008 and 2012. In the UK the crash provoked a five year recession and a whole series of state spending cuts, primarily impacting working class lives and whose effects are still with us today. At the time, however, they were pedalled by the then PM David Cameron as the necessary sacrifices everyone must make because “we’re all in this together”.

As for China, it was not immune from the effects of the crash. While it was a surprise to some that China held $8 billion of US subprime loans on which it took a ‘haircut’, the initial impact on the economy, not least due to loss of markets for the manufactured goods it exports, was huge. As elsewhere, the Chinese state resorted to a massive monetary stimulus and tax reductions for businesses. A spectacular building boom ensued. The local governments who had largely funded it became mired in debt while China’s GDP growth rate plummeted from 13% in 2007 to 9.7% a year later and 9.4% in 2009. It has never again got near to 13%.(12)

In the wider world, the economic recession triggered the uprisings and anti-government protests of the Arab Spring, unforgettably inspired by Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit vendor who burned himself to death in January 2011 as a protest against unemployment and the difficulties of even surviving. After several weeks of protests the 24 year rule of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali came to an abrupt end. From Tunisia, the protests spread to Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Bahrain. Rulers were deposed, civil wars have occurred, millions more have become seriously impoverished. Capitalism remained standing.

Since the crash the spectacular interest rates which encouraged the working class to speculate with their own houses and allowed them to get up to their necks in debt have disappeared and the financial services sector is more tightly regulated. Yet this has only given way to an increase in ‘shadow banking’ — that ‘complex adventure playground’ whose share of global financial assets rose from 25% after the 2007-08 crisis to 47.2% in 2022, higher than the 39.7% of conventional banks.(13) Finance capital still dominates the world economy. By far the most part of the trillions of dollars which were pumped into the financial system remain ... in the financial system, whose chief purpose is to refinance existing debts! Moreover,

Including equity and debt, the size of financial markets grew from slightly larger than the global economy in 1980 to almost four times larger today.(14)

Since the IMF’s estimate for global GDP at the end of 2023 was $105 trillion this means that the nominal value of global financial capital = approximately $420 trillion. This, despite the inestimable losses incurred by the global financial crash of 2008. Those losses eclipsed all previous financial crises, including the 1929 Wall St. Crash. The multi-trillion dollar cost of propping up the global financial architecture was far more than its estimated $20.49 trillion value by our financial spokesperson above. Yet this is the shape of things to come. A capitalist world, where the fragility of the world’s enormous financial services industry is a reflection of its insuperable crisis of low profit rates in the ‘real economy’: insuperable, that is without colossal devaluation of real capital values.

What About the Real, or is it the Surreal, Economy?

The 2007/8 crash appears to have briefly spurred a sense of “we’re all in this together” on the part of the representatives of national capitalist states. At any rate Russia was finally accepted into the WTO in 2011, almost twenty years since it applied to join. It had taken until the mid-1970s for the volume of world trade to pass its mid-19th century peak but import and export and other restrictions remained. Now, though, nearly all the world’s large economies (with the inauspicious exception of Iran) shared the same access to each other’s markets.

Significantly too, by 2007 China had overtaken the United States to become the world’s largest producer of manufactured goods. Even despite the great financial crash, China’s huge manufacturing capacity helped double the country’s GDP per capita between 2003-2013. Meanwhile the manufacturing capacity (machinery and plant) of the United States has become progressively under-utilised. Not counting the 2008 slump, the average utilisation rate over the last twenty years is 75%, ten per cent lower than in the three post-war decades.(15)

Nevertheless,

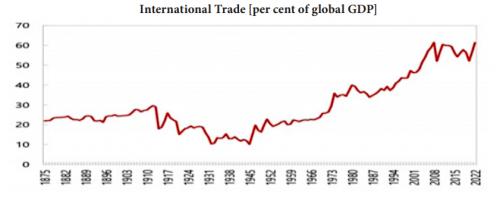

According to the WTO, the volume of world trade today is roughly 45 times the level recorded in the early days of the GATT (4500% growth from 1950 to 2022).

World trade values, as a percentage of GDP, have ballooned by almost 400 times from 1950 levels. [See graph](16)

The overall global picture is that merchandise trade increased steadily as a proportion of world GDP until 2008 (financial crash), diminished until 2016 and then began to increase again. By 2022 merchandise trade as a portion of global GDP had just about returned to the pre-crash level. (Global average = 45.22% in 1992; 62.08% in 2008; dropped to 50.56% in 2016 and latest, 2022 figure is 61.86% of global GDP is accounted for by trade in goods.) This seems straightforward enough and is borne out by the above graph.

And yet ... the actual movement of global merchandise is anything but straightforward. More often than not, the production of commodities today notoriously involves the toing and froing of partially finished goods, often from country to country, with firms at every step in the chain claiming their share of ‘added value’ until the final finishing step can claim the profit on the finished good. Without the development of container shipping in the 1980s, and the subsequent expansion of freight rail networks, the explosion of cheap consumer goods imports from China which offset the impact of the economic crisis on the working class in the old capitalist heartlands would not have occurred. The enormous cheapening of the cost of freight transport since then has dramatically changed the shape of manufacturing industry and supply chains so that not only the component parts but the manufacture of any single commodity is more than likely to have taken place in more than one country. And, if it is true that:

Most of the world’s manufacturing takes place in one of three cross-border manufacturing networks centered on the United States, Germany and China (previously Japan until about 2007) while cross-border trade of finished goods and services accounts for only one third ...(17)

it is also true that the complexity of supply chains makes national trade figures something of a fiction.

Gadgets assembled in China (or, nowadays, Vietnam) and shipped to North America or Europe are filled with imported components, including components made in the United States, just as German cars are built with East European parts and American trucks are filled with Mexican content. Yet the statistics produced by customs officers attribute all of the value of the imported inputs to whichever country happens to ship the finished product.(18)

With this qualifying situation in mind we can consider the evolution of world trade patterns. Thus, China remains the top merchandise exporter but by 2022 its share in world exports had declined to 14%. The United States, in second place, accounted for 8% of world merchandise trade and third ranked Germany, 7%.

Meanwhile, the percentage of China’s GDP stemming from trade in goods has fluctuated during the same two decades, from 31.61% in 1992, to a peak of 63.97% in 2006 prior to the global financial crash, then declining steadily to 35.13% of GDP in 2022. As for the United States, merchandise trade since the early 1990s has not significantly grown (15.3% in 1992) and, financial crash notwithstanding, has remained at around 21% of GDP since 2007. In other words, the more ‘advanced’ an economy becomes, the less it is reliant on commodity manufacture and trade.

Which brings us back full circle to the fact that the global manufacturing workforce now accounts for not much more than 11% of the overall number of wage workers. It is the surplus value produced by the sweat of these workers that will increasingly provide the cheap consumer items for workers in the ‘advanced countries’ that have been the bedrock of capitalism’s survival mechanism ever since the 1970s: workers, for example who toil in the garment industry in Bangladesh making clothes that are shipped across the world. The sector employs as many as four million people, but the average worker earns less in a month than a U.S. worker earns in a day.

Coincidentally, the world’s fifty largest companies by ‘market capitalisation’ employ slightly more workers (approximately 25,600,000, about 11.7% of the global workforce). Apart from Saudi Aramco, they all happen to be based in the United States. Seven of the top ten companies are currently ‘cash hoarders’, i.e. they are not ploughing profits back into production. They are all based in the United States and have been dubbed the Magnificent Seven: the technology giants that have driven the rise in US equities over the past year or so — Amazon, Alphabet, Nvidia, Tesla, Meta, Apple and Microsoft.

Their savings in 2023 are reckoned to have exceeded $300bn. The ultimate owners of these savings are the rich households that, directly or indirectly, hold shares in such companies. The share of disposable income going to the very rich has been rising consistently since 1980, increasing inequality within many of the world’s largest countries. Since the rich save more of their income, this has led to the accumulation of a large savings surplus among wealthy individuals which has risen in tandem with corporate earnings.(19)

So there it is: the fruit of capitalist globalisation. Not a peaceful world of plenty where everyone can enjoy the bounties of the wealth they help to create but an increasingly fractured world where the rich are squabbling over how to get a bigger slice of the pie. For sure it is a pie of dubious value but one they are already telling us it is worth our fighting over.

ERCommunist Workers’ Organisation

Notes:

(1) Three works in particular have been consulted for this section on the falling rate of profit: World in Crisis, A Global Analysis of Marx’s Law of Profitability, a collection of essays edited by Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts (pub. Haymarket Books); The Long Depression, Michael Roberts (also Haymarket Books) and Andrew Kliman, The Failure of Capitalist Production (pub.Pluto Press).

(2) The Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall Since the Nineteenth Century and a World Rate of Profit, Esteban Ezequiel Maito in Carchedi and Roberts loc cit.

(3) Kliman, op.cit. p.84

(4) Maito op.cit. p.147

(5) The so-called McKinsey Global Institute, Manufacturing the Future, The Next Era of Global Growth and Innovation, 2012

(7) data.worldbank.org

(8) See International Labour Organization World Employment and Social Outlook, Trends 2024

(9) For a more extensive analysis of service work see our five part series on Capitalism’s New Economy, notably on our website, notably Part 3: The Booming Financial Sector

(10) Abby McCain, 25+ trending financial services industry statistics (2023) zippia.com

(11) Karl Marx, Capital Vol 3 Penguin edition, p.608, part of the illuminating chapter on money capital and real capital.

(12) See for example, China’s Policy Responses to the 2008 Financial Crisis, Jiawen Yang, available online.

(13) John Plender, The overlooked threats to the global financial system in the Financial Times, 16.4.24

(14) Ruchir Sharma, What Went Wrong With Capitalism, article in the Financial Times 25.5.24 [Sharma has just published a book under the same name.]

(15) Matthew C Klein and Michael Pettis, Trade Wars Are Class Wars (Yale University Press), p.77

(16) Edward Price in Financial Times 21.2.23

(17). op.cit. p.27-8. ibid p.29

(18) See, for example, Bangladesh: Workers Struggle for a Living Wage (2011) or Garment Workers Struggle Against Vicious Exploitation (2006) on our website

(19) John Plender loc cit

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #24

Out now!

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.