You are here

Home ›Capitalism's Economic Foundations (Part III)

Introduction

Regular readers of Revolutionary Perspectives will know that we have been republishing, with minor additions, the article “The Economic Foundations of Capitalist Decadence”. Originally published in 1974 this was one of the founding documents of the Revolutionary Perspectives group which became part of the Communist Workers’ Organisation in 1975. Written half a century ago its central premises have stood the test of time, and in the first two parts we have only made light edits to the original.

However, in this part we enter the period through which, for all the turmoil and change of the last half a century, we are still living. Given that turmoil, we have naturally developed a longer perspective than that posed in the original. In fact, as early as 1976 we had already decided that the coming of the crisis and the revival of the working class resistance across the world to its consequences meant that though the question of “war or revolution” was now on the agenda, it was not necessarily in the immediate sense. The economic struggle of the 1970s (“money militancy” as we called it amongst ourselves) did not automatically give rise to a class consciousness of the need to get rid of the system, even if that system was exhibiting more and more contradictions. Our explanation of the causes of the crisis that emerged then has remained, but after half a century it would be an admission of sterility, if we did not take in subsequent events, as well as expand on those issues where we have since developed our analysis further. This, and the next part of the series, will thus be more heavily edited than the first two. This one will end in the period in which it was originally written, the end of the post-war boom. This was when the working class, faced with attacks on living standards, initially through a huge hike in inflation, responded with strikes and insurrections across the world. These led to the birth of new organisations of the Communist Left like the CWO, and the rejuvenation of already existing ones like the Internationalist Communist Party (Battaglia Comunista). For our new generation, it led us to Marx’s analysis to explain the material reality through which we were living. However, what we could not see in the early 1970s, was how the system would react both to the end of the cycle of accumulation. and to the resistance of the working class to the attempt to make it pay for that crisis. The next, and final, part of this series will summarise the articles we have written since about all the twists and turns of the subsequent capitalist response to the end of this cycle of accumulation – a cycle whose central problem, the need for massive devaluation of capital, still has not been resolved.

One other thing we have had to do over the years is define the term “decadence” against misinterpretations which suggested it meant that capitalism was bound to collapse in short order. Modes of production take centuries to rise and fall and their contradictions can lead to new developments, and sometimes even apparent expansion, before they finally fall. Even then economic contradictions alone do not end class rule. As we wrote in Internationalist Communist 23:

We are dramatically living through the decadence of capitalism, we can identify certain phenomena in which it can be seen but we obviously cannot foresee when this period will historically end. In the absence of an alternative capitalism could still carry on its mad course for centuries. The decadence of capitalism doesn’t mechanically lead to socialism. It is a methodological error to foresee the natural end of capitalism and the arrival of socialism without revolutionary action by the proletariat. Socialism isn’t the natural outcome of capitalist decadence but the fruit of the victorious struggle of the proletariat guided by its international, and internationalist, party.(1)

Decadence is thus only a useful shorthand term to describe all the features that characterise capitalism in the era of the tendency to monopoly, imperialism and state capitalism, but the basic goad of the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall remains the material driving force of the cycles of accumulation which remain in place, albeit in a different form. They remain critical for understanding where we are today, which is at the end of the third cycle of accumulation of capitalism’s decadent period. This one though poses a bigger threat than ever. The journalists of the ruling class talk of a “polycrisis”, with economic stagnation, pandemics, imperialist war, environmental degradation and global warming all threatening, not just the future of capitalism but potentially the future of humanity itself. There is no guaranteed outcome. We are entering one of the periods described by Marx in the Communist Manifesto where we will be faced with either the victory of the “contending” i.e. working class, or the common ruin of us all. Knowing where we are though is only the first step. Neither revolutionary minorities nor the wider working class can wait with folded arms to see what happens. The time to get organised, both collectively and politically, is already long overdue. This series is intended as a contribution to that effort.

The Age of Imperialism and State Capitalism

The Era of Capitalist Decadence

The outbreak of world war in 1914 was the decisive manifestation that capitalism was henceforward a decadent mode of production. But since we have already explained that the falling rate of profit is the basic motive force of capital accumulation, during both capitalism’s ascendancy and its decline, how are we able to assert categorically that world capitalism is now a decadent social system and has been since approximately 1914, although it has still managed to continue to accumulate and even “expand” the productive forces? Let us first emphasise that we say “approximately 1914” as the date for the beginning of capitalism’s decline. A mode of production does not suddenly become decadent overnight, and it can be argued that capitalism had fulfilled its historic task of creating the world economy and establishing the material foundations for communism some time before 1914. However, with the development of monopoly capital and the world economy, a point is reached where the strictly economic crisis of the cycle of accumulation is no longer sufficient to rejuvenate the accumulation process. Centralisation of capital has proceeded too far and there are now too few small, unproductive capitals to fall by the way side. Devaluation of capital as a result of the devastations of world-wide imperialist war is the only solution to the crisis of global capitalism.

In the previous parts of this study, we have seen how the counter-tendencies to the falling rate of profit prove to be ineffective or else lead to imperialism, and eventually world war, once capital is established as the dominant world mode of production. The rise of global capital means the end of laissez-faire or classical capitalism. The accumulation of capital after the First World War could only take place on the basis of constant and growing state intervention in each national economy and the gradual absorption of civil society by the state — hence the existence of the tendency towards state capitalism throughout the world. This, besides involving increasing state ownership and control of the means of production, fiscal policies which attempt to control the economy, also involves the stimulus of waste production (i.e. production which, from the viewpoint of global capital, cannot lead to further capital accumulation) of which the most pronounced expression has been arms production. With classical competition now subsumed under a situation of permanent inter-imperialist rivalry, the booms and busts now present themselves as world economic crises, often accompanied by growing arms production since ultimately the mammoth devaluation of capital needed to enable a new round of accumulation can only be resolved by war, itself a prelude to a new period of reconstruction. The history of capitalism since the start of the twentieth century has been the history of this cycle of crisis — war — reconstruction.

The two World Wars served as means of devaluing capital and permitted a realignment of the imperialist powers(2), but this in no way affected the relative position of the less advanced states who henceforth have been mere pawns in the manipulations of the inter-imperialist rivalry of the advanced states, since it is difficult for the so-called “developing” countries to compete on the world market independently of the imperialist powers.

From the viewpoint of the proletariat, on the other hand, the existence of global, decadent capitalism means also the existence of the material possibility of world revolution and the institution of communism as a higher mode of production. The world revolutionary wave of 1917-21, in spite of its defeat, proved that communism was no longer a utopian ideal, but a practical possibility. But more than this, the First World War proved that the continued existence of the capitalist mode of production was a “fetter” on the development of the productive forces and the institution of communism by the proletariat is essential if society is not to sink into barbarism.

Statification Immediately Before, During and After the First World War

We saw in the discussion of imperialism that state expenditure was increasing as a proportion of the total national income of the advanced states from about 1870 onwards. Armaments, as we saw above, comprised the largest single item of state spending, but other important items were education and public utilities (services with a high technical composition, such as gas and water supply). In 1909 the British Government indicated how far the needs of decadent capitalism were sustained by the State with the formation of British Petroleum (BP), with a government controlling share.

It was in the US however where the tendencies to monopoly of the “Gilded Age”, noted in the previous part(3), threatened not only to kill off the development of new capitals via monopoly pricing but even to distort the political process. In response to protests from organised labour, farmers in the “Granger Movement”, the founding of an Anti-Monopoly Party, the first anti-trust law, the Sherman Act, was passed in 1890. Under the laissez-faire (and Social Darwinist) regime of President McKinlay it remained largely unused. It was only after his assassination that his successor Theodore Roosevelt, an enthusiastic supporter of an American Empire, would apply the act to bring the likes of JP Morgan and Rockefeller to heel. It was bizarre that a government had to to act “to protect competition” (which capitalist claim comes naturally to the system) but it was the beginning of a process where even today markets are regulated and even “made” by the state.(4) Roosevelt though did not go so far as to nationalise actual industries but forged a relationship with them where government contracts became the main source of national planning and capital. The seeds of the post-Second World War “military-industrial-Congressional complex” had been sown, and by that time, and in the post-war boom, industry leaders would seamlessly pass in and out government service.(5)

The outbreak of war in 1914 accelerated this development towards statification in all the leading capitalist powers with central governments taking more or less direct control over production for war purposes. In Imperial Germany after 1916, Rathenau’s control of the economy was so great that it was called “state socialism”, whilst Lloyd George, describing the men who helped run his Ministry of Munitions, said,

... “All the means of production, distribution and exchange” were aggregately at their command.(6)

Many specific aspects of this state intervention were revoked after the war but others remained and state capitalism as a tendency of all capitals was firmly established. The tendency towards statification of the economy is not just the result of the need for production within national states to be geared to the military requirements of war, although this need accelerates and emphasises the trend. A more important reason can be traced to the chronic lack of surplus value as a result of the cripplingly high organic composition of capital. Faced with stagnating industries (whose surplus value is too low to provide for a further increase in constant capital) the state has been forced to try and avoid collapse of the economy by adopting what had hitherto been the function of the market, i.e. promoting the formation of an average rate of profit by redistributing surplus value throughout the economy.

In the course of capital concentration, more surplus-value comes to be divided among relatively fewer enterprises, a process by which the market loses some of its functions. When the market mechanism ceases to “square” supply and demand by way of capital expansion, it complicates the formation of an average rate of profit, which is needed to secure the simultaneous existence of all necessary industries regardless of their individual profit rates. The average rate of profit, ... implies the “pooling” of surplus value so as to satisfy the physical needs of social production which assert themselves by way of social demand. Capital stagnation, expressed as it is as defective demand, hinders an increasing number of capital entities from partaking of the social “pool” of surplus value. Control of surplus value becomes essential for the security of capitalism and the distribution of profits becomes a governmental concern.(7)

Hence the reason for the marked increase in state control over banking, credit, etc., government subsidies and outright nationalisation of many basic industries after the First World War, particularly with the onset of the 1929 crisis. Thus, for example, the French Government lent money to nearly all its shipping lines, to civil aviation companies, to insolvent banks and nationalised the railways. The British Government:

... achieved the amalgamation of the railways (1921), the concentration — indeed the partial nationalisation of electricity supply (1926), the creation of a government sponsored monopoly in iron and steel (1932) and a national coal cartel (1936)...(8)

In Nazi Germany, despite Hitler’s rantings against Bolshevism, state control of the economy proceeded apace. Capitalists were organised into the “Estate of Trade and Industry”, the workers into the Labour Front, whilst in February 1938 Goering was made economic dictator in order to realise the “Four Year Plan”.

The measures ... introduced were not the product of a specific Nazi ideology of economics. They were rather the type of scheme adopted, though with much less vigour, in many countries in the 1930’s nowadays summed up in the term ‘Keynesianism’. They were in part based on the ‘war socialism’ introduced in Germany during the First World War.(9)

In Italy in 1933 the Fascist Government set up the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (IRI):

... a permanent industrial holding-company to aid the government’s programmes of autarchy and rearmament, it continued to limit its operations to industries and services in which private enterprise was willing to invest sufficient funds.(10)

In both Italy and Germany economic recovery was based on armaments production and savage exploitation of the working class, though in fact total social output of both countries fell between 1929 and 1938.(11) We shall see below how this mechanism “aids” accumulation under decadent capitalism. However, statification (in the sense of state ownership of industry), although on the one hand assists the redistribution of surplus value and the general propping up of the economy, on the other, further reduces the profitability of the private sector, since it is mainly by directing surplus value from the latter that the state is able to finance its enterprises. The same process whereby the state attempts to equalise profit rates between industries with high rates of surplus value (which tend to be in Department II) and those with low rates of surplus value ( which tend to be in Department I) operates in fully state capitalist economies (so-called “communist” states), but here it is easier to transfer funds from one industry to another, since the state, acting as one huge entrepreneur, is in direct control of the total national capital. In all modern capitalist economies the unprofitable sectors which are maintained by the state represent an increase in the cost of production from the point of view of the economy as a whole, and thus contribute to further lowering the rate of profit.

The accelerated efforts to ‘rationalise’ production after the First World War by means of ‘scientific management’, ‘labour-saving’ devices, introduction of bonus systems, etc., were desperate attempts to offset the falling rate of profit by increasing the rate of exploitation in those industries which were still profitable. In Britain and France the decline in the standard of living of the workers is apparent by the fact that real wages fell to below the level at the beginning of the century, whilst in Germany, the “share of wages in the national economy dropped from 64% in 1932 (itself a significant drop from the 1928 level) to 57% in 1938.”(12)

Nevertheless, attempts to increase both relative and absolute surplus value helped to increase the growing numbers of the unemployed in all the advanced capitalist states, and central governments again stepped in with further nationalisations, social security schemes and public works to try and maintain production. F.D. Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States was the most ambitious of these. New Deal measures never actually “primed the pump” of capitalist accumulation despite the propaganda claims, but socially it helped to hold the system together through the Great Depression. By 1937 it was already clear that state spending alone would not be enough to end it. Instead imperialist tensions that had mounted during this economic crisis led to more “beggar my neighbour” policies as tariffs rose and “autarky” or “imperial preference” were proclaimed as national imperatives. Rearming in the face of these tensions may have raised profit rates for armaments manufacturers but only added to the drive to all out imperialist war in 1939 and 1941. It would be this which would ultimately destroy capital values in such massive quantities that would be the signal for the start of a new round of accumulation and the longest secular boom in capitalist history after 1945.

In the USSR the isolation of the 1917 revolution to a single country produced not socialism but a different variant of state capitalism. With world revolution now seen as years away, the New Economic Policy (NEP) was adopted in 1921. Lenin was perfectly frank that it was a step backwards to “state capitalism” but he always held the illusion that state capitalism would provide a halfway house to socialism. Even the Russian Left Communists, who had denounced any attempt to establish western-style (later to be called “the mixed economy”) state capitalism in Russia, did not see that total state ownership of the productive forces did not equal socialism (although Engels had warned of that). Throughout the 1920s the debate in the USSR was about what direction to take in accumulating capital. Bukharin emerged as the defender of continuing NEP (and building up agriculture first by concessions to the peasantry) whilst his former Left Communist colleague, Preobrazhensky, called for more rapid industrialisation (a policy supported by Trotsky). These “super-industrialisers” of the Left Opposition were defeated by Stalin through his control of the Party apparatus but that did not stop him stealing their policy in 1928. This was not, as Stalinists and most Trotskyists have maintained ever after, the start of the drive to socialism, but was in fact the initiation of another model of state capitalism. It was one which would later carry out a lot of appeal for states which had been under the yoke of colonialism and sought a way to accumulate without having to rely on the capital investments of their former imperial masters, especially after the Second World War. Stalin made it quite clear that the motive for the Five Year Plans was not to create a better life for Russian workers (whose exploitation would provide the surplus value for these plans) but to create a military machine which would be able to resist the attacks of the Western powers which, even in 1928, he was convinced were preparing to attack the USSR. It was, as the Nazis were to say a little later, “guns not butter”. During the 1930s though, when mass unemployment was ravaging the Western economies after the Wall St Crash, the Five Year Plans gave the impression that a fully planned command economy (wrongly dubbed “socialism” in the USSR and “communism” in the West) was superior to the traditional capitalist economies. Alongside of a strike wave and housing occupations in the immediate post-war period, it was to play some part in the adoption of welfare and social security measures in the so-called “free world” as the economic and ideological competition between the two dominant powers after the Second World War developed into the Cold War.

The Post-War Boom

Thus after the Second World War there was no relaxation of wartime control of the economy as had happened after the First World War. In fact, state capitalist tendencies became more and more emphatic. State expenditure as a percentage of GNP grew dramatically. (See the state expenditures and public debts table below). In the USSR, the fourth Five Year Plan was inaugurated in 1946; France adopted the “Monnet” Plan and nationalised Renault, coal, gas, electricity, the bank of France, the large commercial banks, Air France, and the largest insurance companies, whilst Britain’s list is no less extensive. Whilst state capitalism in the US has, as we have already noted, largely taken the form of government defence contracts, German, Italian and Japanese recovery in the post-war period of reconstruction was initiated by Marshall Aid from the US and maintained by making use of pre-war state control. In Italy, IRI (see above) grew enormously, producing 60% of the country’s steel, owning Alfa Romeo and employing 200,000 engineering workers, besides controlling most public utilities and works; whilst in Germany,

Far more than in any other capitalist country during this period the bourgeoisie ... made use of the state apparatus, and the monetary and fiscal system to force capital accumulation...(13)

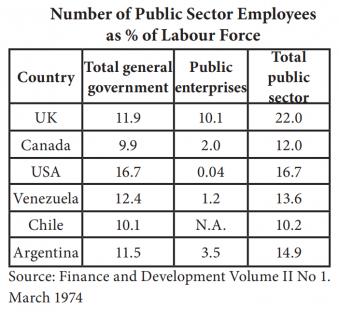

This growth of state capitalism meant that even in the supposedly free enterprise West, the public sector now universally emerged as incomparably the largest employer. (See the public sector employees table below). It should be noted that direct government control was largely in the basic industries which require a high mass of profits to maintain capital renewal and accumulation. The fact that the state was forced to take them over is indicative of the historic crisis itself where the tendency towards equalisation of the rate of profit was breaking down. This explains why the trend towards nationalisation initially intensified further when the post-war boom ended at the beginning of the 1970s. With the state controlling UCS and Rolls Royce, and further statification in the form of the National Enterprise Board, and the nationalisation of British Leyland and the shipbuilding industries imminent, Britain led the way in this universal development.

Inflation as a Permanent Feature of Decadent Capitalism

A large part of government spending which accompanies statification of the economy is in fact unproductive — i.e. expenditure which does not lead to a further accumulation of capital. The whole of the tertiary sector (social services, etc.) as well as arms production (see the following section) can be subsumed under the same heading of unproductive expenditure. Nevertheless, this increase in unproductive spending does not in itself lead to inflation (i.e. to rising prices). If we remember that at the level of the economy as a whole, total prices tend to equal total values, then it is clear that from the point of view of total social capital, such spending represents a drain on the ‘pool’ of surplus value and hence contributes to a further lowering of the rate of profit. Inflation, however is the result of an expansion of the money supply without a corresponding increase in the amount of value produced.

In other words, rising prices, which mean no more than the fact that a larger amount of currency must be exchanged to purchase any single commodity, are a reflection of the devaluation of money as it seeks to re-establish its own real value in the face of an expanding supply of money. The consequences of an increase in the money supply without a corresponding increase in the creation of value can be illustrated in terms of bourgeois classical economic theory, where M = volume of money, V = velocity of circulation, P = prices and T = output, and where, under equilibrium conditions, MV = PT. Clearly, any increase in M without an equivalent increase in T would lead to P (i.e. prices) rising. Unproductive expenditure as such does enter into the equation. The key factor in an inflationary situation is the expansion of the money supply at a rate faster than the increase in production of new value (or “output” in classical terms). Thus, no matter how unproductive capitalism was, there would not be inflation if there was no expansion of the money supply. There would, however, be a very big crisis of unemployment.

In the post-war period the state has been increasingly forced to resort to expanding the money supply partly in order to avoid direct attacks on the wages of the proletariat and attack them indirectly by undermining real purchasing power. Although direct attacks have been, and still are, an important source of government revenue, they are unable to provide the full amount of revenue necessary for the growing number of state responsibilities and deficit financing (i.e. a situation where the state spends more money than it receives from taxation) has been a common feature of all “mixed” economies since the First World War and particularly after the early 1930s when the gold standard was finally abandoned.

In order for the state to be able to control the supply of money it is necessary for each national economy to be free from the constraints of a metallic conversion standard. Throughout the nineteenth century the money supply of national economies had been closely tied to the amount of actual gold or silver (bullion) held within the state boundaries. Paper notes issued were legally convertible into metal coinage and the extent to which notes could be issued was limited by the obligation to ‘back’ paper money with metal coinage held in banks and convertible at a fixed legal rate. Thus the supply of money was limited by the stock of bullion held by the banks within each national state. The outbreak of the First World War saw the abandonment of the international gold standard as the belligerent states met the gigantic costs of financing the war largely by the simple method of printing money. Thus, by 1918, increases in the issues of paper money in Germany were five times the 1914 figure, in Britain, four and a half times the pre-war figure, and in France, almost four times the 1914 sum. Since this increased supply of money was financing the waste production of war and not leading to the production of new capital, prices soared — 245% in Germany, 230% in Britain and 353% in France.(14) The devaluation of currency which accompanied the abolition of the gold standard within the various national states provided a short-term increase in competitiveness for the commodities of the devaluing country sold on the world market, as prices were lowered in relation to commodities from other states. Such an effect could only be temporary, since it only encouraged competing states to go off the gold standard and devalue their currency. By 1936 all those ‘gold bloc’ countries which had previously tried to maintain the gold standard had abandoned it and devalued their currencies.

In the 1930s, just as during the First World War, going off the gold standard enabled central governments of the advanced capitalist states to increase the money supply and further expand their intervention in the economy. As we shall see below, the greatest increase in government spending was due to the massive increase in arms production, but the fear of “political unrest” by the proletariat in a situation of mass unemployment also led the state to extend existing welfare services and engage in the construction of public works.

This huge increase in waste production which was largely financed by deficit spending could only lead to increasing inflation and a growth in the public debt, as evidenced by the table above.

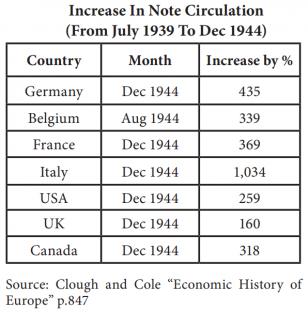

The tremendous cost of financing the Second World War was again met largely by central governments borrowing from banks in return for government bonds or treasury bills, thereby expanding the money supply. The table below clearly shows the increase in note circulation during the Second World War. This huge increase in the money supply in order to finance the war led to rampant inflation in all the belligerent states towards the end and immediately after the war as measures to fix prices became ineffective. The policies adopted to overcome inflation again could only be temporary solutions to the problem.

In the West the implementation of Keynesian measures saw the more or less conscious extension of policies which the state had been forced to adopt since the First World War. Keynes thought that the periodic crises of capitalism could be averted by manipulation of interest rates to encourage investment and by means of deficit spending and public works to maintain employment during times of depression — the resultant increase in the national debt would be repaid during the ‘boom’ period. In fact what has occurred is a permanent increase in the national debt of all the advanced states and inflation has proved to be a permanent feature of decadent capitalism. For instance,

Prices in Western Europe rose by 66 per cent between 1947 and 1957. This was a compound rate of increase of more than 5 per cent per year, a rate roughly equal to the yield of government bonds (before taxes).(15)

According to Keynesian theory, gradual inflation is a healthy rather than an unhealthy feature of national economies, since it encourages businessmen to invest and increases the competitiveness of exports on the world market. Nevertheless, if we remember the reason for the existence of inflation in the first place (expansion of the money supply at a faster rate than the production of new value), then it is obvious that inflation must become more than a ‘gradual’ process if the rate of expansion of the money supply continues to outstrip the rate of value production. As we shall see, this was the case in the 1970s, with the development of a world-wide “recession” which brought to an end the long boom of the “thirty glorious years” as it is dubbed by French bourgeois economists.

Imperialism and Underdevelopment

To Keynes the Second World War proved that any economic system could have full employment if it so wished and he was frightened that the end of the war would only bring back unemployment on the scale of the 1930s. However, in the immediate term he need not have worried. The massive destruction of the productive forces during the Second World War provided a new basis for economic recovery.

Throughout Europe railroad lines, marshalling yards, and port facilities lay in ruins. Machinery had been worn out through constant use and under-maintenance. Mines had been exploited so mercilessly that a super-human effort was needed to restore them to their pre-war efficiency. Agriculture had suffered from over-cropping... And the labour force of most countries had sustained substantial losses.(16)

Whilst Germany, Japan and Italy had been devastated by the war the same could be said of the economic basis of most of the “victorious” powers. The USSR had lost twelve million soldiers and a further 8 million civilians, the UK 11,800,000 tons of shipping, and France 45% of its entire wealth. The exception was the USA where the war had provided a massive boost to production but left its industrial base untouched. Although the war had produced a massive devaluation of US constant capital which had been unable to accumulate during the war, there had ben no physical destruction of means of production. This gave it the power to dictate the economic shape of the post-war new world order. It was to be a world divided between two very unequal imperialist blocs: the USSR and the Eastern European satellites it occupied on the one hand, and the USA with its Western European associates, eventually suitably stripped of their colonies, on the other. Even before Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin met to divide up the world at Yalta in February 1945, the US had strong-armed the other Western states at Bretton Woods (New Hampshire) into accepting the dollar as the new yardstick for international trade. In the new world order member states would peg their currencies to the US dollar, and to ensure no return to the “beggar my neighbour” currency devaluations of the inter-war years, the USA would peg the dollar to gold, at a price of $35 per ounce. Part and parcel of the arrangement was the setting up of the World Bank, charged with acting as creditor to the IMF with transactions inevitably in dollars.

The USSR did not ratify the final agreements and in 1947, at the UN General Assembly, the Russian delegate, Andrei Gromyko denounced the Bretton Woods institutions as “branches of Wall Street” and the World Bank as “subordinated to political purposes which make it the instrument of one great power”. Whilst the USSR and its satellites now controlled a territory spanning most of Europe and a huge part of Asia it was the weaker imperialism to emerge from the war. Its only way to escape from the hegemony of the US dollar was to ensure that the currencies of the territories it occupied remained non-convertible.

Whilst the USSR was reduced to dismantling and transporting to Russia all the constant capital it could lay its hands on from East Germany, the USA had a different problem. As the only power with its productive base intact, its problem was that its Allies were no longer in a position to buy US commodities, unless their economies recovered too. There was a threat of recession here too with all its consequences. From November 1945, through 1946, the biggest strike wave in the history of the USA, fuelled by a rapid rise in inflation and involving more than 5 million workers, largely outside of the trade unions, occurred. The challenge for US capital was to find a way to improve the situation of the working class by reviving both its own domestic economy, and the economies of its allies. Thus in 1947 the USA began to implement the Marshall Plan for its allies in Europe. Essentially this meant financial aid to countries like Italy and France where Communist Parties loyal to the USSR were rising in popularity but even in places like the UK, with no large Communist Party (in 1945 the CPGB had one MP), Marshall Aid was accepted by a Labour Government which used it to pay off some of the bankrupt British Empire’s war debts. New York now definitively replaced London as the financial centre of the world. The USSR to escape dollar domination refused the not entirely disinterested offer of aid, and would not allow its satellites to accept Marshall Aid either. Instead it founded the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) in 1949, not only to discourage countries in Eastern Europe from participating in the Marshall Plan but also to counteract trade boycotts imposed by the USA, Britain, and other Western European countries.

Such was the economic basis not only for the bi-polar imperialist division of the world but it would also lead to the “longest secular boom” in capitalist history. It was not the short-term aid of the Marshall Plan which created the conditions for this boom but the massive devaluation of capital brought about by the war itself. The whole world, especially the US, the USSR and Western European and East Asian countries, experienced unusually high and sustained growth, together with something that had seemed previously unachievable – virtually no unemployment. It was a dramatic contrast to the 1930s and given its length it posed the question as had the “Roaring Twenties” in their day – had capitalism escaped from the cycle of boom and bust which had characterised its history?

But reconstruction had its limits and by the 1970s the rise in the organic composition of capital had brought back the crisis, though not in the form of the nineteenth century business slump.

The business-cycle as an instrument of accumulation had apparently come to an end; or rather, the business-cycle became a “cycle” of world wars... Wars are not unique to capitalism; but the objectives for which capitalist wars are fought are. Aside from all imaginary reasons, the main objective, made patent by the policies of the victorious powers, is the destruction of the competitor nation or bloc of nations. In its results, then, war is a form of international competition. It is not so much a question of competition by “extra-economic” means as an unmasking of economic competition for a bloody and primitive struggle between men and men.(17)

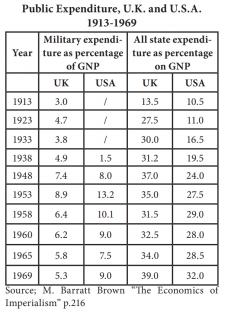

This explains why the method of regenerating accumulation under decadent capitalism has been inseparably linked to the growth in the production of the means of destruction. The table below merely indicates the growth of arms expenditure in Britain and the U.S.A., but by 1962, £43 billion was being spent annually on military budgets and arms expenditure “[c]orresponded to about one half of gross capital formation throughout the world”.(18) Arms production is waste production in that it does not lead to the production of new value for total social capital. True, one national capital can ease its economic problems by selling arms to another, but the money used in the transaction represents the crystallised form of value produced by the labour of the country’s workers. And what can it produce with the arms once it has got them?

Given that a sophisticated nuclear weaponry is not purchased for hunting, it can only be used for the purpose of destruction: that is, arms production destroys value rather than leads to its creation. Hence this imaginary “counter-tendency” to the falling rate of profit is no solution for global capital and in the end can result only in a further crisis, which, under decadent capitalism, ultimately means war.

We have already outlined the main features of capitalist imperialism in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Capitalist competition is now between nation states subordinated to imperialist blocs rather than individual firms. But, whereas under ascendant capitalism it was possible for individual firms to grow through a purely economic competitive struggle, in the age of imperialism the centralisation of the economy at the level of the nation state has taken this process to its ultimate limits under capitalism. Imperialism is the internecine struggle of each capitalist state to carve up as much of the globe as possible, whether as sources of raw materials, investments, markets, or as a strategic base from which to better secure these benefits. Imperialist competition has in its armoury all the tactics of diplomacy, trade wars, sanctions and favoured nation agreements, but ultimately these only have meaning when backed with sheer force of arms. Since the crisis of decadent capitalism has its ultimate expression in inter-imperialist war, it is therefore understandable why capitalists prefer “guns not butter!”, armaments expenditure rather than social benefits like education and housing, as the particular form of waste production.(19)

Since 1914 imperialist war has stretched in an almost unbroken chain, though the most striking example obviously remains the Second World War, which followed a period of massive expenditure on arms to prevent a renewal of the crisis of the early 30’s. Even leaving aside Britain, France and the USSR, arms expenditure rose by 144%, 142% and 103% respectively between 1937 and 1939.(20) Whilst the First World War completed the destruction of British capitalism as the most dominant world imperialism, the Second World War clearly established the USA as the leading capitalist state in the world, though faced with an increasingly dangerous rival in a USSR which had seized much of the industry and territory in Eastern Europe in order to fund its own post-war reconstruction.

The history of the post-war world was one in which both major imperialisms have attempted to gain greater control of the globe in an attempt to offset the decline in the rate of profit through an influx of a mass of profits from abroad. Hence, in the Cold War, imperialist conflict largely took the form of proxy wars from the Korean War, the war in Vietnam, the wars in Africa, and the various Middle East crises right up the USSR’s invasion of Afghanistan, all shattered the uneasy “peace” of decadent capitalism. Imperialism is the product of a world economy dominated by a few advanced capitals of a high organic composition. Before the First World War it was thought that this also meant the physical domination of territory – colonialism. The dominant powers at the time thought that they had to take direct control of territories in order to extract whatever value they could from them. Although Lenin correctly thought that the export of capital was the main driver of imperialism he also considered that anti-imperialist struggles of national liberation would cut off the imperialist powers access to super-profits in the colonies and would thus deliver a major economic blow to capitalism. He was wrong on two counts. Firstly, as anti-Marxist historians(21) have easily demonstrated, with the notable exception of India, colonies in general were not very profitable for imperialism. What they fail to note is that, at the time, the expectation was that they would become profitable, whilst the other motive for occupying lands in Africa, and elsewhere, was often a negative one – to deny rivals the use of a particular territory. Secondly, the administrative and military costs of colonialism were such that more subtle and vastly more profitable methods of dominating these countries after independence (soon to be dubbed “neo-colonialism”) came to be developed after the Second World War. Although nominally independent in a political sense the ex-colonies of the ‘new’ “developing” “Third World” state have found it difficult to break significantly onto the world market. After the Second World War the gap between the leading imperialist powers and the “developing” countries has widened. In 1952-54 US per capita output was $1,870, to India’s $60 and Egypt’s $120. In 1969 these figures were $4,240 for the USA, $110 for India and $160 for Egypt.(22) In 2022 the figures were $70,246.6 for the USA, $2,256.6 for India and $3,698.8 for Egypt.(23)

The failure of the developing world to follow the “take-off” path of the earlier capitalist states as this time cannot be divorced from the interests of the imperialist powers. Having failed to extract enough surplus value from their own labour force, the imperialist powers must attempt to extract surplus value from the underdeveloped regions, but by doing so they prevent that surplus from funding accumulation in the underdeveloped countries, and thus further destroy the basis of reproduction of capital in those areas. Thus, the imperialists are faced with a dilemma:

To keep on exploiting the backward areas will slowly destroy their exploitability. But not to exploit them means to reduce even further the already insufficient profitability of capital.(24)

“Aid” as an attempt by the advanced states to try and alter this situation has merely exacerbated it, given the dominance of the law of value. No “aid” is given unconditionally and, since it is capital, it therefore functions as capital, i.e. it is lent on the merits of its expected returns in terms of profits and interest. One calculation has reckoned that after payment of interest and debts on previous aid, all Latin American countries (excluding Cuba) made a net loss of $883 million in 1965.(25) Cuba, at this time, was favoured more than any other country in a world dependent upon imperialism and was the recipient of $3,000 million in “aid” from the USSR. Despite receiving better terms, Cuba’s economy continued to stagnate. Because the USSR was the weaker of the major imperialisms, it offered lower interest, longer term loans to undercut its competitor in the “aid” market. There was nothing munificent in this, as Cuban and other workers whose surplus value is used to pay off the interest on their countries debt already know. The other weakness of the USSR in the post-war imperialist game was that it could support national liberation struggles by supplying weapons but could do little to help them economically once they had achieved independence as the fate of Vietnam clearly demonstrated.

The most telling reason, however, for the difficulty of underdeveloped economies in the twentieth century to establish a firm industrial base is the domination of the world market by capitals of a high organic composition. As we explained earlier, because competition forces each capital to sell at roughly equivalent prices, there is a constant drain of value from capitals with a low organic composition to those with a high composition. Further, because profit rates have a tendency to equalisation, those states with a low organic composition find that they do not have a sufficient mass of profits to fund renewed accumulation. As Rosa Luxembourg saw quite clearly in her Social Reform or Revolution,

It is the threat of the constant fall in the rate of profit, resulting not from the contradiction between productivity and exchange, but from the growth of the productivity of labour itself... (which) has the extremely dangerous tendency of rendering impossible any new enterprise for small and middle sized capitals. It thus limits the new formation, and therefore the extension of placements of capital.(26)

Thus, it is not surprising that underdeveloped countries have fallen heavily into debt in an attempt to borrow the capital which they cannot produce, so that,

The external public debt of the developing countries rose by about 14% p.a. in the 1960’s. In June 1968 the recorded debt stood at $47.5 billion.(27)

Some saw the rise of command economy regimes in the less developed states modelled on the USSR as an alternative state capitalist solution to the problems of the chronic effect of the insufficiency of surplus value production in these areas.(28) However, its adoption in such places as Cuba and the much-vaunted China represented, not a solution to the problem, but a further indication of its existence. “Foreign capital” having failed, local bourgeoisies attempt to harness the centralising power of the state to concentrate sufficient surplus value for accumulation. Hence they hope to achieve “national liberation” from imperialist domination. Cuba we have already mentioned. China, however has a large population and large resources, it had developed an atomic bomb and launched satellites in the 1960s, but even Sinophiles recognised that:

In spite of exceptional advances, China is still far from a decisive economic take-off ... The supply of grain per head of population remains the same now as that which statistical calculations show obtained in the ‘belle époque’ of the Kuomintang ...(29)

The law of value operated here just as anywhere else. Not even the centralisation of a planned economy could direct enough surplus value into the independent development of capitalism. And just as the post-war boom was coming to an end in the “free world” in the early 1970s the indications are that the USSR and its satellites were also facing a downturn. We cannot of course calculate the rate of profit for those economies at that time, but we can infer from growth rates that all was not well. In the period 1951-5 growth rates throughout Comecon were twice what they were in the 1960s and none of the major targets set in in the Five Year Plan (1971-5) were met.(30) For both sides in the Cold War “détente” was not about taking real steps towards peace but came from a desire to reduce the arms race. Whilst the costs of the Vietnam War had contributed to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system by 1973, for Comecon arms production was taking up such a large portion of its slowing GDP growth that it was becoming unsustainable. This was the Brezhnev era in which corruption and low labour productivity were coupled with rising rates of alcoholism and a dearth of consumer goods. Attempts to alter course would have to wait until his death in 1982 by which time the USSR was embroiled in its own Vietnam after desperately invading Afghanistan in 1979.

Meanwhile the economic problems of both China and the USA had brought about the first steps in their rapprochement after Nixon’s visit to China in 1971. The new approach was a result of the failure of Chinese attempts at autonomous development such the Great Leap Forward in 1958 and the subsequent stagnation after the break with the USSR in the mid-60s. However, by the end of the 1970s (Mao died in 1976) and the start of the 1980s both the Chinese Communist Party and Western leaders and businesses stumbled on a mutually beneficial way to deal with their separate problems. For Western capitalism it provided a way to defeat a working class which had stubbornly resisted attempts to make them pay for the crisis throughout the 70s without producing a solution of their own. Restructuring of industry in the West (often taking the simple form of capital right-offs) would be accompanied by massive investment by Japan, South Korea and Western finance capital in China (and smaller places like Mexico) where millions of workers on very low wages could be put to work. It is to the economic consequences of deregulated currencies, financialisation and globalisation, plus the simultaneous collapse of the USSR, that we turn in our next issue.

ERCommunist Workers’ Organisation

Notes:

(1) See Refining the Concept of Decadence

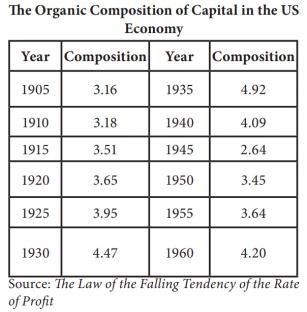

(2) See, for example, this table of The Organic Composition of Capital in the US Economy

(3) See Capitalism's Economic Foundations (Part II)

(4) For a more detailed account of this change in US Government action see Tim Wu The Curse of Bigness – Antitrust in the New Gilded Age

(5) The most famous being the boss of General Motors, Charles Wilson who entered the Eisenhower Administration in 1953. At his Senate hearing it is alleged that he could see no conflict of interest between his huge shareholding in General Motors and the interests of US imperialism. Journalists reduced this to the famous phrase “What’s good for GM is good for America”. Wilson did, in the end, sell his shares to get confirmed.

(6) War Memories of Lloyd George Volume I, p.147

(7) P. Mattick Marx and Keynes, pp.115-6

(8) E. Hobsbawm Industry and Empire, p.242

(9) D. Childs Germany Since 1918, p.59

(10) E. Tannenbaum Fascism in Italy, p.112

(11) Clough and Cole An Economic History of Europe, p.764

(12) See “On the analysis of Imperialism in the Metropolitan Countries: the West German Example” by E Altvater et.al. in the Bulletin of the Conference of Socialist Economists, Spring 1974, p.6. A useful explanation of the German “economic miracle”, though we do not share the author’s view that Eastern Europe and the USSR are anything but capitalist.

(13) ibid. p.9

(14) Figures taken from Clough and Cole, op.cit. p.734

(15) Quoted in Mattick op.cit. p.147. From J. O. Coppock Europe’s Needs and Resources

(16) Clough and Cole op.cit. p.851

(17) Mattick op.cit. p.135

(18) M. Kidron Western Capitalism Since the War, p.49

(19) Despite the realisation by at least a section of the world bourgeoisie of the obvious

political advantages to be gained by keeping the workers happy.

(20) Figures from Clough and Cole op.cit. p.818

(21) The classical example is D.K. Fieldhouse The Theory of Capitalist Imperialism (Longman 1967)

(22) Key Issues in Applied Economics, 1947-1997 Economist Intelligence Unit

(24) Mattick op.cit. p.262

(25) T. Hayter Aid as Imperialism, p.174

(26) R. Looker (ed.) Political Writings of Rosa Luxemburg, p.69 Though later Luxembourg was to abandon value theory. See The Accumulation of Contradictions or The Economic Consequences of Rosa Luxemburg

(27) Partners in Development (Pearson Report) (Pall Mall Press) p.72

(28) Including Mattick, who, despite his erudition, fails to fully comprehend the law of value and has no concept of decadence. Thus he sees state capitalism as progressive. See Revolutionary Perspectives (Second Series) No. 19 which can be found online at libcom.org

(29) G. Padoul “China, 1974” in New Left Review No.89 p.74 & 76

(30) See “The Crisis of Comecon” in _Revolutionary Perspectives 7) (First Series) which can also be found online at libcom.org

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #22

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.