You are here

Home ›Re-Reading Marx in the Light of the Sub-Prime Crisis

From Prometeo 16 Series VI - 2007

Despite the central banks literally bleeding themselves white to satisfy the financial markets’ demands for liquidity, the financial crisis which exploded last August has now engulfed the world economic system.

Previously optimistic forecasts for the future of the global economy have been replaced by pessimism. One and half points have already been written off global GDP next year, with the year after dropping a further percentage point. However, in the light of the few statistics available, even these predictions are riddled with problems.

Indeed, at the beginning of the crisis Bernanke - head of the Federal Reserve - predicted losses in the sub-prime market of around $100 billion. It now appears that the loss has already reached $400 billion but even this figure isn’t final because it was calculated on the basis of projected losses by a few of the big banks, such as Bank of America ($4 billion), Citygroup ($2.2 billion), Morgan Stanley ($750 million), Merryl Lynch ($2.24 billion), etc.

In reality, there is no-one on the face of the earth, not even amongst the bankers and fund managers, who is really capable of saying how much these losses amount to.

In fact, the way these so-called CDOs (collateralised debt obligations) operate is like a chain letter. CDOs are derived from mortgages issued by the banks at interest rates well above the market rate to house owners who have no secure income, even if they are in debt up to their necks. Once issued they give life to a self-sustaining circuit which is passed on by one bank to another, and from them to high-risk investment funds to end up in the share portfolios of pension funds and savers (especially small savers), growing bigger, like an avalanche, at every step of the process. We are therefore dealing with what are really only bits of paper which for most of the time cannot even be sold before their date of maturity. Thus their value cannot be determined on the market, except as an approximation, from which it is almost impossible to determine the total amount or the eventual connected losses (1).

Given the almost fraudulent and ambiguous nature of financial derivatives, which are precisely what CDOs are, the vast majority of economists maintain that their creation is an anomaly in the system rather than a peculiar characteristic of modern-day monopoly capitalism. Thus, they maintain that the crises which originate from them are simply the result of an excessive production of that particular form of financial capital, something which in itself can be overcome and reabsorbed in the short to medium term assuming the right decision on lowering or raising interest rates. This time, however, the overproduction of these derivatives has reached such a size that the world economic system could only absorb it by passing under the Caudine yoke (2) of at least a reduction in economic growth. The danger is that the sub-prime crisis will have repercussions both for the domestic market and on overall US demand which would then affect the entire world aggregate demand. A considerable number of these mortgages have been granted to finance the consumption of families who, led on by the continuous increase in the value of their homes, have signed up for higher mortgages based on that increase or else to increasing the length of the repayment term linked to the new value of their homes. American families have been historically amongst those with the greatest propensity to take on debts. They have not hesitated, therefore, to get themselves up to their necks in debt under the illusion that the debt would wipe itself out. In the league table of the most indebted families in the world, with a debt to disposable income ratio of 128%, the USA is now second only to the UK (148%) whilst the Italian ratio is only 50%. (3) Once the US Federal Reserve was forced to raise interest rates again, in order to restrict inflation following the devaluation of the dollar, the illusion that mortgages could pay for themselves vanished. At this point many mortgage holders were no longer able to honour their debts or else they were declared bankrupt (in the US (4) even private individuals can be declared bankrupt) and their houses were sold at auction. Others, in order to avoid bankruptcy, sold their houses at knock down prices. As a consequence, not only has the housing market collapsed but so also has the entire system of consumer credit finance based on the speculative revaluation of domestic property values. In spite of this, the majority of economists, though recognising that a very dangerous situation has been created, assume that the fundamentals of the so-called “real economy” are sound and maintain that even this crisis of the international financial system is going to be reabsorbed without a great cataclysm.

For example, Alan Sinai, prominent exponent of the monetarist school of Milton Friedman, who was consulted in the 1980s by the Federal Reserve and then by Bush Senior and Clinton, although very alarmed at the possible repercussions of the sub-prime crisis, in an interview granted to La Repubblica (5) (29.10.07), to the question “So, will there be a recession?” , replied:

Not necessarily. In a period which could last from 6-9 months we will find ourselves in a semi-recession: but the economy might not end up in the red or at the most it will last only one quarter, and then proceed to slow to an annualised rate of growth of 1% or a bit more.

And to the question,

But all this stems from the housing crisis?

he replied,

Yes, though it is difficult to believe it, the importance of this sector in America has no equal. We could end up in a recession even though the manufacturing sector is not in crisis.

It is worth the effort to examine the gigantic contradiction of neo-liberal economic policy here, or what is the same thing, the political economy of the big financial capitals and the banks. On the one hand it claims that the capital which Marx defined as “moneyed capital in the sense of interestbearing capital” (6) is capital - still sticking with Marx - “par excellence” (7), and demands for it the free production and circulation of goods as so many inexhaustible productive sources of wealth.

On the other, as the riddle of the crisis is unravelled, it admits that we are dealing with a form of capital that is clearly distinct, again following Marx, “of productive capital (i.e., of surplus value - editor) and of commodity-capital” so that they can maintain that a deep crisis of the financial system does not affect the manufacturing sector. Now, either it is one or the other.

Either the policymakers’ claim that the untrammelled production of interestbearing capital is a source of new wealth is a lie, or else, they are lying when they claim that it has no influence on the real economy even in the present period of imperialism.

At this point however it is worthwhile digressing a little on this particular form of financial capital.

The Production of Fictitious Capital in General

The production of fictitious capital isn’t an invention of the modern capitalist system. Marx had already identified this particular form of financial capital amongst all the others when he was examining the specific elements of banking capital. In Capital Volume Three he wrote:

Bank capital consists of 1) cash money, gold or notes; 2) securities. The latter can be subdivided into two parts: commercial paper or bills of exchange, which run for a period, become due from time to time, and whose discounting constitutes the essential business of the banker; and the public securities, such as government bonds, treasury notes, stocks of all kinds, in short interest-bearing paper which is however significantly different from bills of exchange. (8)

And in relation to government bonds he gives an immediate clarification:

Let us take the national debt ... as illustration.

The state has to pay annually to its creditors a certain amount of interest for the capital borrowed from them. In this case , the creditor cannot recall his investment from his debtor, but can only sell his claim, or his title of ownership.

The capital itself has been consumed, i.e. expended by the state. It no longer exists. (9)

The bond which this credit represents is therefore only capital in appearance, in the sense that its self-valorisation has not taken place as capital invested in the production of commodities. Nonetheless, because these bonds have - as producers of interest - their own autonomous market they can be re-sold and in the eyes of those who invest their own capital to acquire them, the value of these capitals appears to be independent of the real process of production of surplus value, and thus...

the conception of capital as something with automatic self-expansion properties is thereby strengthened (10)

but in reality:

No matter how often this transaction is repeated, the capital of the state debt remains purely fictitious, and, as soon as the promissory notes become unsaleable, the illusion of this capital disappears11 Despite significant differences, this is equally valid for shares because even these are bonds representing capital which has already been spent, or is about to be spent.

Marx wrote:

Even when the promissory note - the security - does not represent a purely fictitious capital, as it does in the case of state debts, the capital-value of such paper is nevertheless wholly illusory. We have previously seen in what manner the credit system creates associated capital. The paper serves as title of ownership which represents this capital. The stocks of railways, mines, navigation companies, and the like, represent actual capital, namely, the capital invested and functioning in such enterprises, or the amount of money advanced by the stockholders for the purpose of being used as capital in such enterprises. This does not preclude the possibility that these may represent pure swindle. But this capital does not exist twice, once as the capital-value of titles of ownership (stocks) on the one hand and on the other hand as the actual capital invested, or to be invested, in those enterprises. It exists only in the latter form, and a share of stock is merely a title of ownership to a corresponding portion of the surplusvalue to be realised by it. A may sell this title to B, and B may sell it to C. These transactions do not alter anything in the nature of the problem. A or B then has his title in the form of capital, but C has transformed his capital into a mere title of ownership to the anticipated surplus value from the stock capital. (12)

Superficially it seems that capital has tripled itself, but in reality it is always the same capital, the initial capital is already spent and what appears as an accumulation of real capital ex nihilo (13) is in reality the accumulation of legal title to an income somewhere in the future. Now, because these bits of paper are not calculated on the basis of a real income, but on the expectation of a future return, there is always a certain guesswork and therefore also a speculative component: whether of losses in bad periods or gains under favourable conditions. So, for example, as far as government bonds to cover the national debt, or more generally, promissory notes are concerned, it would only need the money market to hit some problem that provoked a rise in interest rates for them to be devalued. It’s the same for shares, should there be a change in the situation for whatever extra-economic reason, it would alter the expectations of any future realisation of surplus value which these stocks represent. In treating of the oscillations in value Marx concluded:

To the extent that the depreciation or increase in value of this paper is independent of the movement of value of the actual capital that it represents, the wealth of the nation is just as great before as after its depreciation or increase in value... Unless this depreciation reflected an actual stoppage of production and of traffic on canals and railways, or a suspension of already initiated enterprises, or squandering capital in positively worthless ventures, the nation did not grow one cent poorer by the bursting of this soap-bubble of nominal money-capital. (14)

But this was valid for the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century when the production of fictitious capital was greatly limited in time and space.

The Limits of the Transformation of Fictitious Capital into Real Capital - Yesterday

We have seen that, in so far as they represent the right to a future return, stocks and bonds representing fictitious capital open up their own market and are transferable at any moment into money - or rather into dollar, euro, yen, etc., banknotes, - which in turn can be transformed either into commodity capital or surplus value-producing capital. It is possible therefore - through the simple metamorphosis of one form of monetary capital into another - to bring forward the production of value which in reality has not yet taken place. The time gap that divides the two moments can only be filled in two ways: either by substituting the advance by a deferment of equivalent value or by realising a past production accumulated in the form of commodity-money.

In the expansion phase of the cycle of accumulation and within the limits of a monetary system in which the circulation of monetary capital is regulated, and/or limited by, national boundaries, and in which international transactions are regulated by commodity-money (in general gold or silver), this happens daily. When the real cycle of capital reproduction - which takes place on an enlarged basis - is expanding, indeed in any productive cycle, the discrepancy between advances and deferments that the growing quantity of commodities eventually brings about is easily compensated for and thus it can be kept within the confines of the financial markets. Furthermore, the process of production of fictitious capital on the part of the banks and the various financial institutions is severely limited by the regulations which presuppose the obligation to establish reserves of various types, so that even in periods of difficulties on the money markets the sudden oscillations between rising and falling returns tend to compensate for one another without interfering with the process of the production of real capital. In such a system even the benefits of importing commodities from abroad come within well-defined limits. In a system of international payments based on commodity money imports cannot exceed - except through the opening of credits on the part of the exporting countries - the reserves of commodity money which the country in question has accumulated and which in the first instance represent nothing but the past production of value converted into commodity money and used in the system of international payments, generally gold and/or silver. Thus, in a system where the production of monetary capital in all its forms is regulated, and international payments are in proportion to commodity money the production of fictitious capital is in its turn strictly limited so that the crises which speculative excesses can generate are destined to be reabsorbed through the devaluation of the excess fictitious capital produced within the limits of the money markets.

But today this is no longer the case, and the boundary between the process of accumulation of real and fictitious capital has become much narrower, creating a potentially highly explosive mixture.

Today

Starting at the end of the Second World War, in July 1944 to be exact, changes were brought in to the system of international payments and subsequently also to domestic monetary systems. In the course of time these changes have radically altered the macroeconomic relations between the production of fictitious capital and the process of real capital accumulation.

As is well known, at that time in the small US town of Bretton Woods, the delegates of the various countries which had won the Second World War met to form the so-called Western Bloc. On the agenda of the meeting was the reconstruction of the international monetary system which until then had been based on the gold standard and which in the 1929 crisis had already shown quite a few failings and was no longer considered by the USA to correspond to its interests.

This was the origin of the international monetary system called the dollar exchange standard based on paper money, as if it were commodity money. The issue of the paper money was however to be guaranteed by the convertibility of dollars for gold and the compulsion of the US Federal Reserve to accumulate gold reserves to support an exchange rate which oscillated around 35 dollars to an ounce of gold. With these elements, the system was passed off as simply a more flexible variant of the old gold standard. It wasn’t perfect but it was a lot safer. In fact, however, even if the Agreement aimed to prevent it, by putting paper money (the dollar) at the centre of the system in place of commodity money, this safety clause was defeated because it allowed the creation of credit and fictitious capital on an international scale to be controlled exclusively by the central bank of the country which initiated the production of paper money - the USA. (15)

Paolo G. Conti and E Fazi, in their latest book entitled Euroil, wrote:

For about twenty five years the USA maintained its role of unquestioned leadership and throughout this time the dollar exchange standard functioned very well. The international economy and trade went through a long period of growth. And almost every country, especially those which had come out of the Second World War with devastated economies, like Germany, Italy and Japan, benefited from the stability of the system. (16)

But with the explosion of the crisis of the fall in the average rate of industrial profit - which, beginning in the USA, hit the world economy and remains still unresolved today - the conversion of the dollar into gold could no longer be maintained. In reality the USA continued to print dollars though it had stopped accumulating the quantity of gold reserves prescribed by the Bretton Woods Agreement. Thus, in the summer of 1971, it renounced the agreements and declared the non-convertibility of the dollar.

This imposed de facto a system of international payments based on the production of fictitious capital. What else in fact were these dollars, issued without a cover of gold, but a debt of the USA to the rest of the world in a disguised form? The most immediate and important consequence of the renunciation of the Bretton Woods Agreement, which was the equivalent of the USA refusing to honour its debts, was a ferocious devaluation of the dollar and the explosion of a violent inflationary process during which the USA succeeded in unloading its crisis onto the rest of the world. From a more general standpoint, the declaration of the inconvertibility of the dollar constituted de facto for the USA a new Bretton Woods, in the sense that in so doing the US sanctioned a new system of international payments, entirely based on the issuing of inconvertible bills and their compulsory circulation on an international scale based on fictitious capital. Despite the declaration of non-convertibility, the dollar remained the international means of payment par excellence both in the market for primary products, in particular oil, and as the reserve currency of diverse central banks. Consequently, a situation arose which was simply not imaginable in Marx’s time: variations in value of a circulating monetary capital expressed in a fixed currency, in this case the dollar, were no longer the expression of the real value of a nation issuing that currency - in our example the real ability of the USA to produce wealth - but of the prices of a commodity, or rather commodities, produced abroad, such as oil, and almost all the primary products of strategic importance.

The mechanism functions like this: a nation, lets say Japan, needs oil and buys it from OPEC. In order to do this it must get dollars from the United States for which it exchanges some goods, Toyota cars, for example. The Americans issue the greenbacks and sell them to Japan obtaining in exchange the cars. OPEC instead receives those dollars as payment for oil, thus they become petrodollars: a term which is used to identify the transaction of American value, fruit of the sale of oil in the world. And we are talking of an enormous amount of money. According to a study carried out by the Unicredit Bank in 2006 oil exports have passed $840 billion. Part of these dollars are invested in the economies of the oil producers ... but another part, the most significant is invested abroad, And in dealing with dollars the most natural thing is to choose the USA as the destination for such investments. This represents for the USA the squaring of the circle. The petrodollars are invested in housing, shares, Treasury bonds, mortgages and credit, massively increasing US debt: growing perennially it now has reached $3,000 billion - a figure equivalent to 27% of entire US GDP which is bigger than the sum of the debts of the rest of the world. (17)

The Triumph of Wildcat Banking

And it doesn’t end there. A large number of these dollars continue to return to the USA to be re-invested in Treasury bonds, debentures, shares etc., that is, in securities representing fictitious capital. The wellknown deregulation which has liberalised the production of monetary capital has created the conditions for the new securities which have sprouted like mushrooms. As a result so-called financial derivative products don’t now start, as happened in the past, from a public or private debt or from the formation of a new company through a share issue, as with Treasury bonds, debentures and shares, but from the securities, and bonds themselves, or directly from speculation over variations in their prices, over interest rates and/or those of other commodities, above all oil.

This has given birth to an unending array of financial securities based on fictitious capital. In so far as they are convertible into money, they can be offered in exchange, not only for Toyotas as in our example, but for an enormous quantity of commodities produced abroad. In this way the limits which used to prevent the value of imports exceeding the value of the reserves of commodity money of the importing country (except on a small scale and for a short time), and which were in the past inviolable, have now been broken. And not only that. With the complete deregulation and liberalisation of the use of fictitious capital as the starting point to produce further fictitious capital, Gresham’s Law - by which bad money chases out good - has been confirmed and fictitious capital has rapidly taken over the domestic circulation of the classic greenback.

Thus in many ways we have gone back to the period between the 1830s and 1863, when the National Banking Act was adopted, in which so-called wildcat banking dominated. This was a system in which banks were founded just to issue valueless paper money exactly like the CDOs of our own time or the shares of Cirio, Parmalat and Enron.18 To have an idea of the huge size of the phenomenon lets take 1959-2003, when the production of virtual money which initially grew at the same rate as the number of dollars issued on the basis of the effective value of the commodities produced and sold, progressively grew from a ratio of I to 10. (19) And since 2003 the Federal Reserve has stopped, at least officially, calculating it, claiming that one of the indices used:

Doesn’t seem to contain any useful information on economic activity... Consequently the Board [of the Federal Reserve - ed] has judged that the costs linked to collecting the figures outweigh the benefits. (20)

With the possibility of paying for imports with simple bits of paper denominated in dollars or with a credit card issued on the basis of a mortgage which, as we have seen with housing mortgages, is supposed to pay for itself, the disproportion between US imports and exports over the last three decades has grown in exponential terms and the deficit in the balance of payments In 2006 reached the exact figure of $862 billion which is almost ten times Spain the second country in the list of countries with deficits in the balance of payments. (21)

But perhaps we can make the size of the phenomenon clearer by quoting F.Rampini in La Repubblica on 15 August 2007:

When an American journalist tried to live for a year without the label “made in China” he realised that it was impossible without regressing to the archaic existence of Robinson Crusoe.

“The idea that capital represents something which valorises itself automatically by itself” has assumed such a material, concrete form that what still remains a simple abstraction of value has penetrated the veins of the system to the point where it has taken over the entire process of capitalist accumulation on a world scale and the interpenetration between the two spheres, abstract and real, has permeated the system so much that it has become almost impossible to delimit where one begins and the other ends.

In reality it wouldn’t be able to survive beyond a morning if it did not have behind it the biggest army on the face of the planet ready to run with aid every time this deceit threatens to be unmasked.

Thus, if you want to understand the real effect of the sub-prime crisis and its possible consequences it is necessary to locate it within the entire process of global capital accumulation and relate it to the changed shape of modern imperialist domination.

In a speech delivered to Congress on the 15th February 2006, the Republican Senator Ron Paul declared

When a country equipped with a powerful army and huge gold reserves begins to dedicate itself to the construction of easy money empires with which they sustain their own domestic well-being this is an inevitable signal of its own decline... Today the principle still holds. It’s the process which is different. Gold is no longer the valued currency of the “kingdom”. In its place we have paper.

Today the rule is “he who prints the money makes the law”, at least for the moment. Though gold is no longer used the mechanism remains the same, to induce and oblige foreign countries through our military superiority and the control of the printing of money to produce and therefore to finance our own country. (22)

Now, because the sub-prime crisis has flowed out of the fact that this control of the printing of money is really wavering it is obvious that we are not just talking about the bursting of a bubble but of a crisis of the entire command mechanism of the whole process of capital accumulation on a world scale. For this reason the idea that it can all be readjusted though the simple injection of more fictitious capital into the system’s veins is an illusion at least as far as “the conception of capital as something with automatic self-expansion properties” is concerned.

In reality a crisis of really planetary dimensions is in the offing, one which at the end of the day could make 1929 seem like a mere hiccup.

Giorgio Paolucci(1) For a further deepening of this technical aspect of subprime mortgages see the articles The Subprime Crisis Makes the World Economy Tremble and The Effects of Speculative Finance, both appearong in Battaglia Comunista 9/2007.

(2) The yoke which the ancient Romans used to make the defeated armies of their opponents walk under so that they had to bend their necks to Rome (translator’s note).

(3) The data is from Anatomia di una crisi by E. Della Porta in Il Manifesto 16.11.2007.

(4) And in the UK - translator’s note.

(5) Milan-based daily owned by Silvio Berlusconi (translator’s note).

(6) K. Marx Capital Volume 3 Chapter 29 p.463 (Lawrence and Wishart 1974).

(7) _Ibid/./ (8) _Ibid/./ (9) Ibid, p464.

(10) Ibid, p466.

(11) Ibid, p465.

(12) Ibid, pp466-7.

(13) Literally “out of nothing”.

(14) Ibid, p468.

(15) For a further deepening of this point see the article see the article Il dominio della finanza in Prometeo 14 Serie V 1997.

(16) Paolo G. Conti and E Fazi Euroil Fazi editore p35.

(17) Op. cit., pp63-4.

(18) CDOs are collateralised debt obligations (see Revolutionary Perspectives 43 for a further explanation). For the Parmalat Scandal see Revolutionary Perspectives 31.

The Enron Crisis is dealt with in Revolutionary Perspectives 24.

(19) Op. cit., p58.

(20) _Ibid/./ (21) Op. cit., p60.

(22) Op. cit., p41.

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

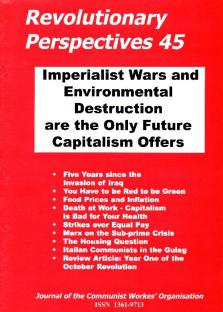

Revolutionary Perspectives #45

Spring 2008 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.