You are here

Home ›Marx is Back

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

Marx, Theses on Feuerbach, 1845, Thesis XI

When Radio 4 recently held a poll to find the 'nation's favourite philosopher', the winner by a landslide was Karl Marx. This, despite a campaign by The Economist to get their readers to vote for David Hume, under the argument that although Marx was already historically irrelevant, it was important to vote against him anyway. Likewise the Church ran an anti-Marxist campaign urging people to support Aquinas. When Marx won there was an outcry by the Daily Mail which ran a two page diatribe against Marx and its version of Marxism, entitled "Marx the Monster". Perhaps this is no surprise, but the real surprise is that Marx himself considered he had finished with philosophy as such by 1845. By this time he had discovered the working class and its particular role in the production of society's wealth. From this time on his thinking was "to revolt against the rule of thoughts" and to recognise that

The production of ideas, of conceptions, of consciousness, is at first directly interwoven with the material activity and the material intercourse of human beings, the language of real life.

The German Ideology

Radio 4's In Our Time programme gave itself the task of analysing Marx and his relevance to the world today but did not even address his fundamental materialist conception of history. Francis Wheen started by saying: "Now is a very good time to go back to Marx himself and what he said and thought and did rather than what was claimed on his behalf". Predictably, over the next forty minutes the panel of experts did the exact opposite. The programme, chaired by Lord Bragg of Blairism, a card-carrying member of the Church of England, prides itself on its intellectual depth and impartiality yet managed to churn up many of the old wooden caricatures about Marx and Marxism. During the frenzy of gob-smackingly wild statements about Marxism they ended up even surprising each other.

The panel consisted of Gareth Steadman Jones, Professor of Political Science at Cambridge, (who, given his lack of any understanding of Marx, has terrifyingly edited The Communist Manifesto and is writing a biography on Marx), AC Grayling, Professor of Philosophy at Birkbeck College and the Guardian's favourite liberal philosopher, and Francis Wheen, journalist and author of Karl Marx (which is reviewed in RP 19). Melvin Bragg chaired proceedings and occasionally interjected with comments like: "There's a lot of anti-semitism in Marx but I don't think you have time to talk about that".

In his lifetime, Marx was no stranger to personal attacks by the bourgeoisie, who have done everything within their power since to discredit him and the methodology, theory and programme for socialism he left the working class. This programme started as it meant to go on by expressing surprise that Marx had won, since most of the commentators saw the collapse of the Eastern Bloc as synonymous with the collapse of Marxism, but more on this later. They went on to discuss Marx's youth and the development of his theories, his study of Hegel (from which they concluded Marx was a determinist and not a dialectician at all) and of Feuerbach. For Gareth Steadman Jones, Marx was 'stuck in the 1840's'. According to him, Marx seized on the importance of the Industrial Revolution (its existence was apparently pointed out to him by Engels, he himself hadn't noticed it), and from this drew the conclusion it could lead to the end of scarcity for mankind. Revolution was never mentioned. He went on to say that Marx set himself two tasks, one to show capitalism was a mode of production like any other which came and went, and the other to show there was something afterwards which could work (which given Marx's supposed determinism would somehow come about automatically), but he failed in both. At this stage, all the commentators were eager to show that Marx's economic theories were deeply flawed and no longer applied to modern capitalism, and that there was no possibility capitalism could ever be superseded by a more advanced society, so therefore there was no point discussing communism itself.

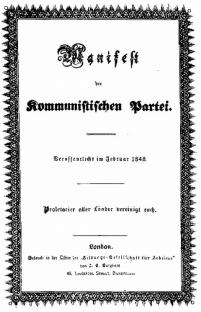

Setting aside the fact that some of the commentators confused a mode of production with 'a mode of property', all felt that Marx's Capital was a deeply flawed work which failed to recognise 'the adaptability or ingenuity' of the capitalist system. For them, Marx failed to understand capitalism because he believed what motored it was the market, and that his central contradiction was that the society of the future wouldn't have a market. Francis Wheen went on to say that Marx himself was hugely in praise of capitalism, that the Communist Manifesto was none other than a hymn of praise for capitalism (the examples he gives are where Marx states the bourgeoisie has accomplished wonders far surpassing the Egyptian pyramids). However, nobody mentioned that Marx went on to say this same dynamic with which capitalism swept away feudalism would in turn destroy capitalism, since it created the material means for a communist society to exist, and a potentially revolutionary class to bring communism into existence through revolution. All agreed that the notion of a communist revolution was clearly absurd and Francis Wheen went on to state that Marx himself realised the error of his ways when writing Volume 2 of Capital which ends with an economic model of a capitalist economy of steady growth without any boom/bust cycles. He went on to state that for capitalism: "...this is how it came to pass. Well, actually, we have had boom/bust cycles..." (In any case Marx shows no such thing in Volume 2. What he demonstrates is the reproduction of the aggregate social capital. He deals with the economy as a whole and divides the entire social production into two major departments: 1) production of means of production and 2) production of articles of consumption. He analyses the circulation of the aggregate social capital, both in the case of reproduction in its former dimensions and in the case of accumulation).

Since it is virtually impossible to unravel this mess, it is probably best to do what Wheen suggested in the first place and actually look at what Marx himself said in Capital. In the preface Marx states: "It is the ultimate aim of this work, to lay bare the economic law of motion of modern society". For Marx, capitalist society - where the production of commodities dominates - is a historically specific mode of production whose peculiar dynamic lies in the perpetual necessity to accumulate capital. Marx, along with early bourgeois political economists like David Ricardo and Adam Smith, recognised that the only source of value is human labour power. The owner of capital buys labour power at a value determined by the socially necessary labour time necessary for its production (i.e., the cost of maintaining a worker and their family). Once the labour power has been bought, the capitalist uses it to bring in over and above the amount paid back in wages. As a result workers produce surplus value for which the capitalist hasn't paid. For Marx this is the root of the exploitation of the working class and the source of capitalism's wealth.

The bourgeois apologists of course argue otherwise but Marx destroyed their arguments which basically assert that money or capital is the source of all wealth. Marx demonstrated that surplus value does not come from commodity circulation, since this is only the exchange of equivalents. Nor does it come from a rise in price, since the mutual losses and gains of buyers and sellers would just equalise one another.

In capitalist production there are two distinct parts; constant capital (machinery, tools, raw materials etc.), the value of which is transferred (either all at once or in part) to the finished product; and variable capital, i.e., labour power. The accumulation of capital involves the transformation of a part of the surplus value expropriated from the working class to be used for new production. As accumulation continues, capitalists, pushed by their competition with each other, are increasingly forced to invest in constant capital at the expense of variable capital, but since it is only living labour that can produce surplus value, profits fall, leading to economic crises. When the weaker capitals find they have insufficient surplus value to recapitalise their investments, they are taken over or collapse. As Marx says, one capitalist kills many.

Such crises led in the nineteenth century to a devaluation of capital and to a decrease in the organic composition of capital which allowed the surviving capitals to start again. This whole process continued beyond Marx's death and with it, an increased centralisation of capital. The search for cheap raw materials and investment in less well developed areas (i.e., places with cheap labour) offset the fall in the rate of profit and expand the world market until capitalism covers the globe. The contradictions in the system, however, only exacerbate themselves. As monopolies emerge, so, too, does misery on a mass scale. The monopoly of capital becomes a fetter on the mode of production. As Marx realised, only the revolutionary working class can end this cycle and the 'expropriators are expropriated', once the working class, the exploited class creates the revolution. For Marx, the dynamism of capitalism, the falling rate of profit, led it revolutionise its means of production, but it was this dynamism which was central to its internal contradictions and meant that ultimately it is incompatible with the interests of humanity as a whole.

However, none of this concerned our panel. When they went on to discuss the Russian Revolution they asked whether Marx had got it completely wrong or whether the Russian Revolution just called itself Marxist. Although we would agree that communism never existed in Russia, this was not because Marx somehow 'got it wrong' or because the revolution was imposed from 'top down'. We have written extensively elsewhere on the Russian Revolution, on the growth of the soviets run not by a handful of putschists but by the Russian working class themselves. The soviets did not lead to communism because the revolution remained isolated in one country where the working class formed a minority and was severely weakened by the civil war caused by the invasion of foreign bourgeois powers. Although private property was abolished, it was not turned into socialised property, rather it was nationalised. Wage labour, money and exploitation all continued to exist. For Marx, and for all subsequent Marxists, communism is a society of freely associated producers, a classless, moneyless society without states or national boundaries, where, as Marx said, the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all. The Russian Revolution was a heroic attempt to start this process. For the bourgeoisie in general, and for this panel of experts in particular, every coup d'etat and murderous regime which massacred workers under the name of communism, from Stalin to Pol Pot to Mao is lumped together with the Russian Revolution.

The programme ended with a spectacular piece of nonsense attacking Marx's materialism. As we stated at the start, Marx's whole "philosophy was a materialist one. For him, just as ideas are a reflection of the real world, social knowledge (i.e. views and doctrines, including religion, politics etc.) reflect the economic system of society, in other words: "It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary it is their social being that determines their consciousness". For him, the dominant ideas in society were the ideas of the dominant class, this was why it was essential for revolutionaries to organise within the class, since the revolution would not automatically emerge just because workers were exploited. This is why Marx was an active revolutionary and not just a philosopher. However, Gareth Steadman Jones ended his contribution with: "Marx's legacy... is that... it isn't economic conditions that determine things but ideologies". AC Grayling agreed by asking the question: "Who was the biggest Marxist in the twentieth century? Mrs Thatcher". This baffling piece of utter absurdity required further explanation, and when it came it muddied the waters further. Thatcher's pronouncement that "there is no such thing as society", argued Grayling, was Marxism because for Marx individuals stood in relation to one another on the basis of their economic relations. When he stated: "That is a very distinctive Marxist idea". what he meant was it's a very classical bourgeois idea. Grayling's fatuous comment seems to show, if we may be allowed to bowdlerise Marx himself, that the philosophers have only misinterpreted the world simply to avoid changing it. For Marx, individuals do not change society, the struggle between classes does.

There is no doubt that, with the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, the majority of the bourgeoisie thought they had buried "Marxism", which they deliberately identified with Stalinist state capitalism, for good. Like their pronouncements that the working class has disappeared, this is more wishful thinking on their part than reality. Groups like ours, and the continuing resistance of working people all over the world to the barbarism of capitalism today, are proof that Marxism lives, that his scientific analysis of capitalism ever more proves to be true, and that his revolutionary theory is the only alternative to the growing barbarism with which capitalism threatens to engulf humanity.

The working class, and its Marxist "philosophy", is a spectre that haunts the bourgeoisie still.

RTRevolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #36

Autumn 2005 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.