You are here

Home ›Radek on the "Defeat" of Brest-Litovsk

With this translation we begin the second volume of our series of translations from the review Kommunist, using the French version published by the Collectif d’édition smolny (collectif-smolny.org). As many will know the review Kommunist was the brainchild of the “proletarian communists”, or “left communists” as Lenin dubbed them, inside the Bolshevik Party in the spring of 1918. The original issue around which they were formed was opposition to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) but as readers of our earlier translations will know they also highlighted their disquiet with certain developments inside Russia.

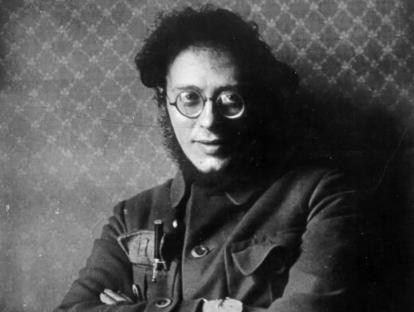

In this article however Karl Radek returns to the theme of Brest-Litovsk which he labels from the beginning not as a setback, or a retreat, but a “defeat”. From this all kinds of disasters were predicted to fall upon the young Soviet republic. Disasters did lie ahead and the “left communists” were right to point to the fact that the introduction of capitalist methods of management would undermine revolutionary initiative in the working class.

However they were on weaker ground when it came to opposition to Brest-Litovsk. Radek had been part of the delegations who had attempted to delay the negotiations and even after an armistice with Germany was signed at Brest-Litovsk the Bolsheviks tried to balance the shame of negotiating with imperialism with the need to spread revolutionary propaganda. Not only did they get the Germans to agree to halt the transfer of troops to the Western Front during the period of the armistice (the German General Staff had been gradually doing so since the collapse of the Provisional Government’s June Offensive) but also to agree to fraternisation between the two armies and to allow revolutionary literature into German-held territory. Radek had already begun organising German and Austrian prisoners of war and even produced a newspaper for them (Die Fackel — The Torch) which was also provocatively distributed to German troops at the Brest-Litovsk station by the Bolshevik delegation!

Radek however took no part in the final negotiations and became a spokesman of the Left (which was the biggest faction but lacked a majority) against the Treaty. Lenin had little difficulty in demonstrating that the Left’s idea of a guerrilla war was pure romanticism. Their own writings where they talked of dying heroically “sword in hand” were a gift to Lenin who compared them to “szlachta”, the old Polish nobility. The irony is that for all the bitter opposition of Radek and others put up to the signing of Brest-Litovsk within a few months they would be accepting that it had been a necessary step and, even later, both Radek and Bukharin came to defend one or other aspect of the counter-revolution they so feared in the spring of 1918. In Radek’s case he would stoop to defending national-bolshevism (and an alliance with the Nazis) in the so-called Schlageter Line in 1923. His career is in itself a salutary lesson for would-be revolutionaries today.

The Foreign Policy of the Soviet Republic

THE DEFEAT OF BREST-LITOVSK marked the end the first period of history of the Soviet Republic and its foreign policy. Throughout its brief course, the Russian Revolution was, militarily speaking, much more fragile than its adversaries. During the October Revolution, only the final scraps of the Russian army remained, worn out, demoralised, incapable of military resistance. Yet, in spite of this, the soviet government embarked upon an audacious assault on international imperialism: it nullified the old Tsarist treaties with its allies and published them (1); through a series of political acts, it attempted to stir up the workers of France and England into a revolt against their governments; it offered the German imperialists a flagrantly unacceptable treaty and, at the same time, began a campaign of revolutionary propaganda on the front to reawaken the forces susceptible to oblige the capitalist governments to take notice of the Russian Revolution and its aspiration of general democratic peace. It is obvious that not one of the representatives nor the intelligent defenders of the Soviet power could have envisaged a specific start date for the European revolution. Everyone understood that, inevitable though it might have been, the timing of its maturation remained unknown.

Nevertheless, the Soviet power pursued a policy of exerting pressure on international imperialism because it knew that the acceleration of the pulse of the European Revolution was a question of life or death for the Russian Revolution. Only the merciless attack on international imperialism and the daily revelation of its politics – which a revolutionary politic had to oppose – could have permitted the Soviet power to sound the alarm bell and call the proletariat of all nations to struggle. If, despite all its efforts, it did not succeed in stirring up the European working masses, even if it was obliged to negotiate with the executioners of the German working class, with its military clique, the Soviet power never sought compromise with this imperialism; faced with the German militarist party at Brest-Litovsk, it unmasked the politics of banditry of Berlin. The Soviet power fully understood the tremendous risks of such a policy, it knew that it could have obtained concessions in refusing to unmask German imperialism; it knew that these revelations of German imperialism were sure to provoke their anger. Nevertheless, it made its choice consciously, knowing full well the need to be magnanimous in great causes, that the initiator of an international revolution must dare, dare again and always continue to dare.

This audacious policy failed. The moment it succeeded in stirring up an initial German and Austrian mass revolutionary movement (2), German imperialism pointed its revolver at the breast of the Soviet power, and the Soviet power surrendered to it. It signed the conditions of peace that mutilated the revolutionary country and economically bled it dry. But this is not the whole story of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Convinced that the Russian Revolution did not have the forces to stand up to the German imperialist offensive, the Soviet power decided to put an end to its policy of exerting pressure against imperialist powers. It resolved to await the European revolution by manœuvering, in the short term, between imperialist states and by accumulating forces for the purpose of a struggle against them later. It would have been absurd to refuse this treaty, to turn our back on a done deal and not to take notice of the current situation with regard to future policy. If, when German imperialism forcefully proposed a “bandit treaty”, it would have been possible not to sign it (every worker in Europe would have understood and approved this decision), the provocative sabotage of the peace, after it had been signed, would be not only incomprehensible for the European working masses, but would have permitted the German imperialists to present the Russian Revolution as a blind instrument in the hands of the Allies. If, at the beginning of the German assault, it had been possible to send troops of revolutionary workers into combat, explaining to them that the revolution was in mortal danger, now, since the Soviet power and the Bolshevik party have done everything to persuade the working masses that they were unable to combat German imperialism and that they had to preserve their forces, the offensive would have been impossible.

The opposition to the treaty of Brest-Litovsk from the Left SR (3) was but an echo of the individual combat tactic of the terrorist intelligentsia, whose audacious heroes substituted themselves for the passive masses. The communist proletarians did not have the luxury of playing at heroism: they had to prepare for a new mass insurrection in the conditions they had inherited from the Brest-Litovsk treaty.

The struggle of the Russian proletarian masses against foreign imperialism depended not only on the objective conditions in Russia, but on the whole international situation. What were the characteristics of that situation? Above all, the total lack of social equilibrium. It would be no exaggeration to say that the cannons that had massacred humanity for four years now stood on the edge of a precipice.

Not one government knew what the following day would hold. They were all demanding enormous sacrifices from the popular masses, none of them knew the limits of their strengths, nor their breaking points. The political realists of the Russian bourgeoisie’s politicians derided our hopes of European revolution as absurd dreams. But we were more persuaded than ever of its inevitability. While the war continued, claiming more victims every day, it increasingly drained the productive forces of all countries involved and imperialist breakdown became ever more inevitable. It was obvious that nobody knew the magnitude of the strength they would need for the whole endeavour to prevail. In February 1918, the revolutionary forces of Europe were insufficient to protect the Russian Revolution from the violent banditry of German imperialism. But afterwards, in ceasing to bet on the European Revolution, the Russian Revolution signed its death warrant. Socialism cannot be realised in one country alone; certainly not in a country so backwards. Capitalist countries are bound tightly together, purely by their chosen economic policies; the Russian Revolution threatened the interests of global capital, which could not remain indifferent to it, every day. The Russian Revolution and global capitalism are in a state of permanent war, declared or otherwise. If the position of imperialism is not unstable everywhere, our own desperate situation and Soviet diplomacy cannot save us. But we have already said that this is not the case, and we can quote one of Marx’s letters to Ruge from 1842: “The desperate nature of the situation: that’s where my hope lies.” (4)

But today, after the signing of the treaty, what are the chances for the European Revolution now? The right wing of the Communist Party (5) declared: “Yes, we hoped and we continue to hope for a European Revolution, but, it has not as yet taken place, hence we are obliged to do business with imperialist camps. We are forced to manoeuvre between them.” Let us examine the theory of this manoeuvre. It is based on the correct idea that, between the Austro-German and Franco-Anglo-American coalitions, in short, between German and English imperialisms, compromise is impossible. That is true. But the tactical and strategic conclusions deduced from this situation by the right wing of the Communist Party are completely false. We cannot clearly deduce from the furious battle that brought the English and German imperialisms to the front in Flanders, that we have an assured guarantee of their incapacity to crush us; as the imperialist trusts continue to fight each other. The defeats on the Eastern Front, the prolongation of the battle, the danger of America’s considerable forces mobilising against Germany (6) – all of this could lead its leaders to struggle against Russia in order to secure the necessary resources to continue the war. These same realities liberated Japan from its dependence on its allies, allowing them to blackmail us and, contrary to their interests, to begin their own offensive against Russia. The more desperate the situation in France became, the more investing billions in Russia became vital for their finance capitalists. In order to recuperate them, the French financial oligarchy was prepared to support Japan in its attack on Russia; worse still, it was ready to renounce its claim to Alsace-Lorraine on the condition that it would receive the support of German capital to get its hands on the dividends of Russian loans. The French rentiers would write off all their financial losses in the military debacles and the futility of war if they could still lay their hands on the cash of a part of the Russian securities they are so scared of losing. As a consequence, despite the depth of the chasm that currently separates the two imperialist camps, we cannot count on a period of any length of peaceful coexistence with European imperialism. At any moment, we could become the object of a more brutal attack launched by imperialist forces.

All foreign policy that relies on a long period of respite and is not prepared to daily resist with the forces at its disposal is a policy of capitulation and not of manoeuvre. Such was the historic example of Kuropatkin (7), who knew only one manoeuvre: to retreat. This policy that does not clearly put a limit on its concessions, and is not ready to fight with weapons, was precisely that of Kuropatkin. Some partisans on the right wing of our party tell us that this policy is identical to that of Kutuzov, who sacrificed territory to buy time. But these representatives of the right wing abandoned Kutuzov’s (8) policy. They signed the peace treaty to safeguard the territory of the Northern Russia. However, Kutuzov bought his time with weapons still on the battlefield.

There are well defined boundaries that must remain uncrossed with regards to manoeuvres that aim to create Soviet power. If it were the State or a bourgeois commander performing the manoeuvre, they may only follow the rules of military art. For them, no possible course of action would be ruled out. They could terminate alliances with all possible adversaries of their enemy. We, on the other hand, have but one ally: the international proletariat, which has begun to mobilise its forces. All of the States between which we are forced to manoeuvre are enemies of our class. It is this that defines the limits of our manoeuvres. If belief in the European Revolution is not a maxim, an icon before which we pray morning and night, and that does not influence our everyday behaviour, then let us not engage in manoeuvres that would weaken the rising forces of the European Revolution. International proletarian solidarity is the indispensable condition of the European Revolution. Every manoeuvre that undermines the faith of the European proletariat in international proletarian solidarity delays the development of the European Revolution and drains the sense out of our policy, whose goal is precisely to maintain ourselves until the European Revolution, and thus to precipitate it.

Every act that links us politically or militarily to any of the imperialist camps is an obstacle to the rising European Revolution.

It is clear that the signing of the treaty at Brest-Litovsk put an end to the political and economic isolation of Russia following the October Insurrection. Between the capitalist world and the Russian Revolution, relationships were forming that we could not renounce. The economic relations with Germany, the immense engagements that we were obliged to uphold, we strove to maintain those relations with the Allies as we did not want to fall into total dependence on Germany. In the first place, we would form commercial relationships with the United States. We would have to borrow foreign currency, which would call into question our position on our older existing loans. If, in building these relations with the capitalist world, we conducted skilful politics, if in making the necessary concessions we controlled them so well that they did not harm our transition to socialism, these relationships would not contradict the anti-capitalist nature of our politics and would help us to resolve the atrocious economic distress of our country, to reinforce the Russian Revolution and, consequently, to precipitate the European Revolution. But by allowing economic concessions to foreign capital to penetrate the economic organism of Russia, we shall save our lives by sacrificing their meaning. If, in order to gain economic profit or to repel a threat, we would call for help from one of the imperialist bandits against another one, if we asked for help from the German troops against the Japanese or vice versa, we would become a stakeholder in the imperialist system, in contradiction with the objectives of our politics. The idea of duping our temporary Allies would demonstrate great aplomb, but alas, would in reality be nothing but a ridiculous utopia. The rest of us, those who have been defeated, whose military force has barely begun forming, instead of manoeuvring the imperialists, we would only become their victims. We would be constrained to helping the imperialists of other countries realise their plans, as was the case for Kerensky. By conducting a relationship with an imperialist coalition, we would be presenting to the proletariat a coalition adverse to their interests, that we are allied with their enemies, and that we would destroy their solidarity with the Russian Revolution. The latter, constrained to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which reinforced German imperialism, has not lost its influence on the European proletariat; it has not become an ally of the bandits of Berlin in their eyes because every worker of Western Europe sees very well that the German imperialists forced it to sign the Treaty at gunpoint. If the Russian Revolution, concealed in the cabinets of diplomacy, had voluntarily formed a relationship with one or the other of the imperialist coalitions, it would have become complicit in imperialism. The call for military help from an imperialist camp, for example, or an invitation to foreign military instructors, would provoke the same reaction from the European proletariat. Given the current state of things, we could not reach out to our old allies. What is more, our allies of yesterday could always become our enemies tomorrow (see the intervention of Japan) and we do not know what the major preoccupations of these instructors would be: helping us in constructing our new army, or espionage. Even the appearance of French, English or American officers in the ranks of our revolutionary army would give the German imperialists a pretext to tell their workers that the Russian Revolution had become a toy of the imperialist allies, undermining the trust of the German working class.

Our manoeuvres do not mean that we have the privilege to operate freely between the two imperialist coalitions. In the impossibility of extracting ourselves from the links of the global capitalist market – since we are obliged to import products – we must reach it in a way that works for us. What is more, we are politically linked. Linked by the socialist nature of our State, linked by the objectives that our current politics aim to pursue. The defeat of Brest-Litovsk brought an end to the period of our first foreign policy, that of our open offensive against global imperialism. Until the revolutionary movement in Europe gains strength, until the Russian proletariat re-establishes itself and feels strong once again, we must conduct a policy to rebuild our forces. This policy excludes the manoeuvres of politicians, plainly revealing conciliation with this or that imperialist camp, for these manoeuvres would not signify the accumulation of revolutionary forces, but the dilapidation of belief in the Russian Revolution. Nevertheless, this does not entirely solve the question of the character of our foreign policy in this current era of transition. If at any given moment we did not use our forces to go on the offensive, that would not mean that we would have to take up a policy of passive defence. Passive defence is always doomed to fail. It would kill any belief in our own forces and allow the initiative to be taken up by the enemy. Instead of passive defence, the correct strategy requires that we prepare an active defence, that is, the weakest monitors their opponent’s moments of weakness so that they can switch to the offensive, albeit partially. The active defence that we could conduct demands that the revolutionary parties of the Russian working class do the work that the Soviet government has renounced in light of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and that they aid the revolutionary movements of other countries.

Active defence requires the workers’ government to take up henceforth a policy of denouncing the two imperialist camps, clearly imposed by the inextricable international situation. We have suffered a terrible defeat, but we have not ceased to be the only home in the world to free propaganda. We shall remain the one light that illuminates the darkness. And we must concentrate our efforts on accelerating the pulse of the European Revolution and not simply await it with folded arms.

The objectives of our foreign policy are clear. It is not military revenge for the debacle of Brest-Litovsk. If in marching with our allies we had reconquered the lost regions of Russia, they would have been rendered not to a socialist but to a capitalist Russia. The same chord that links us to the Allies would strangle our socialist endeavours. Our revenge shall be the European Revolution which will liberate the stolen Russian regions and ensure the future development of the Russian Revolution. The only direction compatible with the interests of the Russian Revolution is that of the European Revolution. Foreign policy and domestic policy are very closely linked. This is why we cannot suppress these characteristics of the foreign policy of the Russian Revolution without emphasising this: insofar as surrender to foreign capitalism leads to an arrangement with Russian capitalism, “wheeler-dealer politics” based on this agreement will undermine the influence of the Russian Revolution on the international proletariat. The Russian Revolution can only stir up the European proletariat as a workers’ revolution. Every act of domestic policy that constitutes a return to the capitalist order weakens the strength of the magnetism of the Russian Revolution, faith in the European Revolution and thus surrenders the Soviet Republic to foreign imperialism, that is to say, to suicide.

The Russian Revolution is suffering a serious crisis. We must not ignore the questions to which this era of transition has given rise, hide them or pretend not to have seen them. But the history of the workers’ movement has known two ways of facing the existing realities during transitional eras: faced with a new situation, the opportunists conform to it, that is, they submit to triumphing capital in order to gain something from it; the partisans of the socialist revolution only take the facts into consideration in order to overcome them. In the current situation, this second approach means an intensification of the construction of socialism in Russia and an internationalist foreign policy of active defence of the revolution.

Viator [K. Radek]

Translation: Tinkotka

Notes

(1) From 23rd (10th) November 1917, Pravda and Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee published the Russian secret diplomacy documents, in conformity with the Decree on Peace of 8th November (26th October) which stipulated that all of the secret treaties of the autocratic regime were null and void. From December 1917, they were compiled under the title Collection of Secret Documents pulled from the Archives of the Former Minister of Foreign Affairs. Between December 1917 and February 1918, seven of these collections were published, unmasking the secret agreements of the past by the Tsarist government, then of the provisional government of Russia with those of the UK, France, Germany, Japan and other imperialist states. The publicity afforded the most scandalous of them, the Sykes-Picot Agreement, provoked indignation and fury amongst the great powers. This agreement establishing the division of the Middle East had been finalised between France and the UK, between the diplomats Sir Mark Sykes (1879-1919) and François Georges-Picot (1870-1951) in complete contradiction with what was promised to Sharif Hussein of Mecca in 1915 by the British in a series of exchanges with Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Cairo. The Franco-Russian Alliance Pact of 1894, under the reign of Tsar Alexander III, was also published.

(2) On 15 January workers in Vienna struck and demonstrated for a peace without annexations at Brest-Litovsk. On 28 January workers in the German munitions industries launched a powerful strike for a peace without annexations and better provisions. Seen as the forerunner of the German Revolution by the Spartakists and revolutionary shop stewards, they were denounced by Ebert’s Social Democratic Party and its unions. As the strike movement began to spread Kaiser Wilhelm II introduced martial law and from 3 February onwards they fizzled out.

(3) The acronym “SR” refers to the party of the Socialist Revolutionaries. The most significant of the Russian socialist parties for a long time, it reclaimed populism and terrorist action. But during the course of 1917, its leaders who were within the closest reach associated themselves with the provisional government and with the policy of alliance with the Convention. An important fraction split for this reason and took the name “Left SR”, and defended positions very similar to those of the Bolsheviks. From December, they participated in the Soviet government for a few short months. Opposed to the signature of all peace negotiated with Germany, they left the Sovnarkom on the 15th March after the ratification of the treaty by the Fourth Congress, a decision enshrined by their Second Congress in April 1918.

(4) This idea can actually be found in Marx’s letter to Arnold Ruge (1802-1880) from May 1843: “You will hardly suggest that my opinion of the present is too exalted and if I do not despair about it, this is only because its desperate position fills me with hope.” Available at: marxists.org

(5) This refers to Lenin and his supporters.

(6) The USA entered the war against Germany on 6 April 1917. The first troops arrived in France in October 1917, and engaged in combat from November. This contribution from America was especially effective from Spring 1918, in particular in combating the great German offensive. The first American army would be officially constituted on the 10th August 1918. At the time of the Armistice, two million American soldiers stood on European ground.

(7) Alexey Nikolayevich Kuropatkin (1848-1925): Russian general and politician, Minister of War from 1898 to 1905. Although reticent towards the idea of a battle with Japan, he was still head of the forces in the conflict that arose between the two powers. His leadership was characterised by excessive prudence, indecision and a chronic hesitancy that led the Russian army from defeat to retreat. He was relieved of his post after the decisive battle of Mukden (10 March 1905). Nicholas II, against the advice of the most competent military experts, judged it a good idea to give him a position again in 1915, and even a command on the Northern Front in February 1916, before relieving him of his duties in July of the same year, following repeated failures.

(8) Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov (1745-1813): general, commander in chief of the Russian forces in 1812, he applied a policy of scorched earth and defended the idea of a controlled retreat until enough forces were concentrated for a decisive battle.

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.