You are here

Home ›The Party Question

The translation which follows is the greater part of an article from Prometeo, theoretical review of the Internationalist Communist Party in 1984-5. It should be read alongside the document which appeared in RP08 on The Role and Structure of the Revolutionary Organisation.

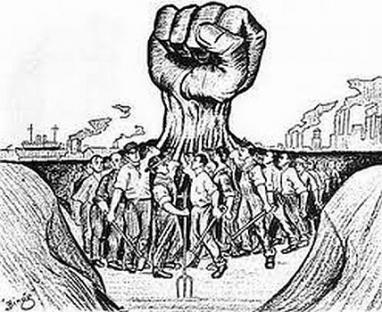

This document looks at various conceptions of the party (and not just those held in the Communist Left) but concentrates on three issues above all. The first is to explain why we reject the notion of a mass party and links it both to Social Democracy and the counter-revolutionary degeneration of the Comintern (which abandoned the model of 1917 where the Bolsheviks were formed into a cadre party of the class in the heat of the class struggle). Instead the Third International imposed social democratic notions of the party on the new communist parties which sprang up after 1917. As mass parties they were in a better position in order to act in defence of the Russian Soviet Republic rather than carry on the work of extending the world revolution.

Another central issue of the document is the need for revolutionaries at all times to work towards the formation of the party even when the social conditions for it to come into existence within the class are weak. Theorising the non-existence of revolutionaries and reducing their tasks to just theoretical elaboration breaks the dialectical link between theory and practice, between the class and its revolutionary minority. Such a view reduces the appearance of the party to the last minute and perhaps to its failure to arrive on time as happened in so many places in the post-war revolutionary wave.

Underpinning it all is the fact that the party does not come from outer space, or wherever, but comes from within the working class and its struggles, and its rise is parallel with that of the general combative consciousness of the class which no amount of voluntarism or short-term tactical shifts can accelerate.

CWO13 October 2016

The Approach to the Question of the Party

Even today it is still an issue; not, as in the past, a debate between Marxists and anarchists, or between councilists, syndicalists, and Bolsheviks; but in a more subtle almost obscure but no less dangerous way. Within the "communist left" the party question is still on the agenda.

In the dark tunnel of the counter-revolution, by which we mean not only the triumph of Stalinism in Russia, but also the distortion of the basic framework of revolutionary ideas, the role and function of the class party has also undergone much revision.

At issue is not the party as such, but its relationship with the class, the uniqueness of its political function in the class struggle, the ever open question of consciousness and its permanence in a so-called counter-revolutionary phase, and finally its tactics as a concrete expression of its political being.

Like many other issues the party notion has suffered heavy criticism from both right and left, in both mechanistic or idealistic ways, not so much as a single object of study and rethinking, but more as an appendix to a counter-revolutionary process that affected the foundations of the newly born proletarian state after Russia’s October Revolution.

Many political elements, in trying to understand a posteriori the main causes that brought about the defeat of the Russian Revolution latch on to what the Bolshevik Party did during, and especially after, the taking and management of power.

Some have seen in the lack of centrality of the party, too influenced by "external factors" such as the Soviets, especially those of non-workers, as one of the fundamental causes that favoured revisionist ideology first and counter-revolution later. Others look at the issue from the opposite point of view, seeing the inevitable preconditions for the process of degeneration in the same party structure, through its decidedly totalitarian centralism and its supposed substitutionism.

These concerns are valid even if their conclusions aren’t. In the twenties and thirties (for latecomers there are no time limits) an analysis of the route Russia was taking was an absolute priority from both the internal socio-economic aspect, as well as, from a revolutionary point of view, the role that the Soviet Republic might possibly still play on an international level.

The first great revolutionary experience, which had allowed the Russian proletariat to create the political conditions for the transition to socialism through the indispensable form of rule of its dictatorship, as the first step in an international revolutionary process, was showing signs of a gradual attrition.

Then as now, a correct interpretation of what happened was, and is, the condition for creating the conditions of a future victory of the world proletariat, even after such a severe defeat. Instead people very often fall into the error of confusing the manner and the timing of the degenerative process with the causes that brought it about.

The first big rock on which the Bolshevik revolutionary experience ran aground was its international isolation, exacerbated by a particularly backward domestic economic situation. The impossibility of creating the basis of the new society within the confines of one nation, the pressing concern to somehow solve the most basic issues of physical survival, and the opportunist aspects of the resistance to international capitalist encirclement came at the cost of increasingly giving up the demands of the revolution itself. All of which provided fertile ground for counter-revolutionary ideology and practice.

The more isolation and encirclement tightened its grip around the Bolshevik experience, the more the worm of counter-revolution was nourished in the revolutionary power structure itself, in the management of state bodies, in the relationship between the party and the class and within the Party itself.

The contradiction between a revolutionary superstructure aiming towards a socialist solution and an economic structure still based on capitalist economic categories was fatal, especially within an international framework that was moving rapidly in a totally negative direction. The second condition clearly had to prevail over the first thus halting the revolution on the threshold of the first step and preventing it from going on to the next, that of socialist construction. Especially fatal was its continuing isolation, so that the consolidation of the productive base on capitalist economic categories, even at the level of state management, would eventually erode, and finally overwhelm, the very political superstructure that emerged from the victorious revolution.

The party was also overwhelmed. Indeed, the start of the political defeat really began with it, as an inevitable reflection of an unfavourable and infinitely impossible situation both at home and abroad. Those who believe that things could have been different if only there was a different kind of party, either an even more centralised one, less influenced by “non-class” factors or, conversely, one more open to the demands of different social components, depending on their analysis and inclinations, would be taking the bull by its tail rather than by the horns. Those who simply see the key to the defeat of the Russian Revolution in the Leninist conception of the party have taken the road to political confusion and are revising one of the fundamental cornerstones of the class struggle.

It is not in the extreme idealism of a pure and uncontaminated party, nor in that of a vulgarly pragmatic party open to all sorts of tactical compromise, that the success of a revolution can be guaranteed. But these roads have been disastrously taken even within the "communist left".

Once again the poor understanding of events in Russia after the revolution, has led to confusion between the causes and the nature of the counter-revolutionary process, triggering the dangerous presumption that the solution to the most important, if not all, the evils that have plagued the international workers’ movement, can be found in a redefinition of what the party is, as well as its role and its relationship with the class in the management of power.

What is the Party?

In the Theses on the tasks of the Communist Party in the Proletarian Revolution approved by the Second Congress of the Communist International, theses truly and deeply inspired by Marxist doctrine, the starting point is the definition of the relationship between party and class. It starts by establishing that the class party can only be a part of the class, never all, perhaps never even the majority of it.

A party lives when it has a theory and a method of action. A party is a school of political thought and then a fighting organisation. The first is a fact of consciousness, the second is a fact of will, more precisely a tendency towards a precise goal.

We repeat these two short, concise, but extremely clear passages by Bordiga on the party issue as essential starting points, even if we do not share all of their implications, especially those he expressed later.

The question: what is the party, before it even constitutes a political-programmatic question, refers, in its content, to the relationship with the class. In other words must the party, precisely because it is the political organisation of the class struggle, the supreme guardian of the immediate but, above all, the historic interests, of the working class, contain the vast majority, or only a part, of the class? Is it possible that the party can represent the interests of the whole, or is the opposite formula true?

Coming out of the byzantine political maze, the question of the distinction between a party of cadres and a mass party was posed historically.

Almost all the communist parties that sprang up in the late teens and early twenties did so under the political inspiration of the Bolshevik experience and the Third International as revolutionary vanguards of the working class, or rather as narrower cadre parties representing the proletarian world. Apart from the purely genetic fact that the vast majority of new parties came out of the old Social-Democratic organisations of the Second International who saw themselves as mass organisations, the revolutionary "minorities" set themselves up as a kind of political opposition to the reformist "majority". The idea of a body of cadres was better suited to the dialectic of the facts than any idealistic ambitions and inclinations, and above all, fitted the only genuinely revolutionary episode: the Bolshevik Revolution.

Theory and a method of action, as preconditions of consciousness and will, can only be carried by a minority, of a part of the class. It is thus idealistic praxis to conceive of the possibility of the acquisition of total consciousness by the entirety of the class, like the gradual conquest of the "spirit".

History has shown often enough how consciousness, doctrine and method derive from the experience of the class struggle, but the class can only adhere to a political programme at certain times and under certain conditions.

The economic and political domination of the bourgeoisie is always such as to inhibit the possibilities of the growth of consciousness within the totality of the class. There are too many factors getting in the way of the development of consciousness. Lenin’s sentence that the dominant ideology is the ideology of the ruling class(1) is not just a clever-sounding abstraction, but a very effective summary of reality both then and now. For him consciousness and the programme, despite being the historical acquisition of the whole class, as the sum and synthesis of occasional and partial episodes, are a political heritage of only a part of it. Precisely for this reason the party is the most advanced and conscious part of the class that unifies its experiences, channels its efforts, and at the same time, overcomes its limitations.

The idealistic conception that claims to identify the political formation of the class as an autonomous process of acquisition of consciousness, ends up by giving the party only marginal and secondary tasks such as from time to time accelerating the class struggle or organising economic struggles. Some see it as a sort of "headquarters" of the proletarian army, denying its primary role, that of an irreplaceable political tool of the class struggle, as a synthesis of theory, method, consciousness and determination to struggle.

It is true that these factors can be identified in the class, but only partially and intermittently. They emerge in ascending phases of the struggle, but are practically non-existent or distorted in periods of complete subjugation or defeat. These elements can only be expressed in a joined-up way and have continuity over time in the party. Only within the political vanguard can all demands arising from the tumult of the class struggle be distilled and tactically and strategically ordered, very often over and above economistic spontaneity, sectionalism and corporatism.

The basic pretext, to which those old and new idealists cling in order not to retreat from their position on the question of consciousness and of self-emancipation of the proletariat, is provided by this simple syllogism: how is it possible to build a new economic and social order, the realisation of a political project based on the disappearance of classes, if the subject of this revolutionary change, the proletariat, is not conscious of its aims? Either the proletarian revolution, like the building of communism, is the result of a historical accident, as improbable as it is random, or the political consciousness for this act has to belong to the class, the whole class and not something that is outside it.

First it should be noted how the idealistic world-view obstinately considers the class and the party as two different categories that are even strangers to each other. The first is the object which the second relates to, but only as a political complement outside the class, as the bearer "from the outside" of something that does not belong to the entire class, consciousness, and so is different from it. According to this view, if first the revolution and then socialism are the products of consciousness and will, either they are the patrimony of the class or they are nothing. The moment they become attributes of the party, would lead in their eyes to some sort of process where the factor of consciousness did not exist or would be outside of the revolutionary subject.

But, in any dialectical conception, the party is a part of the class, not a more or less important appendage, or even a body external to it. They are the same class elements. The more conscious, more politically-equipped and determined make up the party cadres, alongside deserters from the other class, provided they make the revolutionary programme of the proletariat their own. It is from the heart of the class itself that its vanguard emerges. This is due to the nature of the class-party relationship, which can be seen in the very question of consciousness as a strict dialectical relationship between two forms of existence which express themselves in the same class. Otherwise you get lost in the subtle problems of one above another, one internal and the other external, in romantic Hegelian ideas about the maturation of a class ego. That's why it is only through its vanguard, or rather its party, that the class can, and is, able to express itself in a conscious and unified manner.

The class is changeable due to its economic and political subjection to the bourgeoisie. It attacks and retreats, makes gains and is defeated, and gives rise to countless demands, which are always partial and limited and often contradictory. In some historical phases of its existence it bursts with force and violence onto the social stage driven by its objective conditions, and certainly not by a definite programme.

The dialectical conception has never peddled the illusion that consciousness ripens automatically within the class and we just have to wait for a revolutionary movement. If the Bolshevik Party and Lenin had expected this to happen, not only would they have encountered a lot of difficulties, but the October Revolution would never have come about, neither in 1917 nor in the decades that followed.

The real problem has always been different. How can the spontaneity of individual sections or the vast majority of the class be connected to the programme of its political minority? In other words it is only with the presence of the party that sectional demands can become general, that the economic grievances can come out of their rudimentary form to take on political shape, that the immediate content of one struggle, of a section of the class, can be framed within a strategic vision.

The party of cadres, and its quantitative limitations, does not depend on any elite selection process, but on the actual unfolding of the class struggle, which, until the decisive revolutionary event, has to submit to the economic and political domination of the bourgeoisie. This breaks up and isolates struggles and opposes the interests of one category to another. Above all it obscures class consciousness to the point of making the historic goal ever more confused and remote.

It is utopian, as well as politically foolish to think that the class party can, in a particularly favourable situation, such as in a revolution, unify in its structure the whole class or its numerically more consistent part. This will never happen other than in the mental masturbation of idealist thought, but what will happen is that the party, in periods of direct confrontation, will have behind it, though not in it, very broad masses, in order for there to be any hope of a revolutionary outcome.

The conception of the mass party, instead of, or in opposition to, the party of cadres, began to make inroads in the political perspectives of the Third International, and consequently in the tactics of the Communist Parties at the same time as the beginning of the process of political retreat that took place in an increasingly isolated Russia after 1921. It is possible at this time to identify the same logic in the theoretical development of the mass party as that which accepted united fronts and the workers’ and peasants’ government. This was the first step in the rehabilitation of Social Democracy as part of a progressive abandonment, and not just verbally, of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

If the "tactical" goal was not the proletarian revolution for the overthrow of the bourgeois governments, but a kind of "tactical alliance" with the Social Democrats for a hybrid coalition government with the, as yet, undeclared aim of rallying around Russia those governments that were not hostile to its internal "achievements", it followed that little or no purpose would be served by having politically combative communist parties well known for holding revolutionary positions, but incapable of having any influence in fighting bourgeois institutions. Mass parties would be much better and get more rapid results in line with the new objective. They would be more flexible in tactics, more articulate and attentive to cross-class demands, or rather they would be mass parties that could make their voices heard not only in the streets but also in the traditional institutions of bourgeois power. It followed that, this greater political weight was a condition of the wider social groups that entered the party organisation. If there was no sign of an international revolution, it might as well consolidate the revolution that already existed in Russia. It counted little with the future "gravediggers" of the Revolution, that the October conquests themselves would be safeguarded and strengthened only on condition of supporting other revolutionary episodes. Either Russia had to emerge from isolation or it would collapse in on itself with no possibility of escape.

But now the new road had been mapped out and there was nothing to be done but follow it to the end, and on this road there was absolutely no place for those same cadre parties that were created by the perspective of revolution a few years before.

The transformation of cadre parties into mass parties was not a result of a different tactical approach in response to the difficulties of the time, very dangerous though they were although not irreversibly so, but to the change in strategic objective.

The possibility of building socialism in one country, once accepted, despite the demands of proletarian internationalism became the strategy which the Third International tended towards in order to create a sort of security zone around Russia. In other words, when the prospect of international revolution was declining the level of support for the needs of a "domestic socialism" increased. The less the need for revolutionary vanguards and the more the need for mass parties was invoked.

With its aims radically changed, it was also necessary to alter the way the Third International operated. It was not possible to pursue the creation of leftist governments that functioned as a political buffer for the weak Russian state structure without equipping the Third International with the right tools.

The Idealist Approach to the Party Question

It is the question of consciousness which really decides the various positions on the role and function of the party.

According to the purest idealist interpretation, consciousness being an internal phenomenon of the totality of the class, as a purely spiritual category, is an irreversible factor of self-consciousness superior to all forms of social conditioning, so there is automatically no, or a very limited, need for a party.

If it were possible for the entire class to come together as events developed, to overcome from time to time, in the course of the struggle, its internal divisions, its mere immediate demands, become more united and add increasingly advanced political perspectives to its demands but above all if it was able to develop a revolutionary programme and the tactics which flow from it, the party would not only not help, but it would become a structure whose awkward presence, in the course of the class struggle, would ultimately adversely affect, or worse, inhibit the progressive evolution of consciousness and its possible political gains.

So the only bodies that can fulfil the organisational and political tasks are those that arise spontaneously in the course of the struggle as a conscious act encapsulating both immediate tactical demands and strategic aims. The presence of a party organisation, within these institutions would distort their class nature, it would affect the political situation, above all by carrying the germs of the counter-revolution.

Councilists and anarchists of all persuasions, have made this setting a kind of dogma, not only rolling their eyes whenever they hear mention of the party, but with the "wisdom" of history, attribute to it the responsibility for the failure of the Russian revolution.

Without going to this extreme, and without taking on board in toto the method and conditions which effectively place the anarchist movements and councilists outside and against the revolutionary Marxist positions, very often the idealism, while remaining in support of the so-called party system, can be kicked out the door only to reappear at the window. An example is provided by those groups who swear by the irreplaceable necessity for the class party, but in fact they mediate the task, sidelining its function to the more theoretical and abstract rather than being operationally effective. Or as a mere bearer of ideologies, provider of armchair tactics, jealous guardian of "sacred principles", and as such incapable of taking part in the actual class struggle that, in spite of the metaphysical expectations of idealists, is always so complex, contradictory, sometimes treacherous, never linear, and certainly never pure.

History has on many occasions demonstrated that the class can spontaneously go beyond the messianic wait-and-seeism of maximalist political positions, better suited to the observation of social phenomena than in developing them into political objectives.(2)

In the first case the party is seen as the provider of slogans as generic as they are irrelevant such as “the generalisation of the struggle”, “the transformation of economic struggles into political struggles”, or invoke the need for of radicalisation without intervening in the "nitty gritty" of the struggle itself, and especially in not equipping itself with tools to link it with the class. Beyond a few slogans every political statement remains a dead letter. Such an unreal position, which deliberately remains on the sidelines of the rocky road of class struggle, is the inevitable result of the idealistic assumption that revolutionary class consciousness develops on its own anyway, choosing its own tactics and establishing its own programmatic strategies. Thus there is nothing left for the party to do other than promote these developments whilst remaining at a safe distance. There is no alternative and there is nothing more to do.

In such a framework the role of the political vanguard is debased to that of accelerator of struggles, more by definition than as a real reference point, a headquarters of the class rather than its political synthesis. The result is the inability to grow with subsequent demands of the struggle, to give themselves the appropriate tools from an operational point of view in order to establish a dialectical relationship between the spontaneity of the struggle and its political goals. In other words these conceptions of the party compel the vanguard to work at the edge of the class struggle where it's easier to be overwhelmed than to politically influence its course.

In the second case the party gives the appearance of a mummified structure sustained only by the codification of its inner workings. It survives, if it succeeds at all, by alternating this with "external" periods, based more on its internal needs than on any political life blood coming from the class struggle. If it is true that we cannot talk of a revolutionary party unless it has acquired an enormous political experience by refining and practising a method of analysis, and succeeded in establishing tactical lines in accordance with its strategic perspective, it is also true that if all this remains mere potential without expressing itself in "deeds", or postpones them to an objectively more favourable situation, then what we are faced with is a purely fictional organisation.

A first effect that hit all of those organisations that have a “wait-and-see” model of the party, as a knee-jerk reaction to a long counter-revolutionary period on the international stage, was reflected in the fact that the more they have theorised and practiced non-intervention because it is pointless, or even counter-productive given the situation, the more they have cultivated a conception of the party bordering on the metaphysical.

The more the party is estranged and isolated from the class struggle, the more its peculiar characteristics suffer the distorting effects of its self-image as omniscient. Paradoxically, just as in the first idealist theory the party ends up as an appendix, an external accessory to the evolution of the class struggle, so in the latter the party ends up becoming like a "first unmoved mover" whose main features are absolute infallibility, a mechanical and deadening centralism, and an underlying idea which denies that internal disagreements are a prefiguration of socialism.

Both idealistic approaches, both of underestimation and overestimation of the party form, before, during and after the revolution are the product of an incorrect method of approach, from half-digested lessons at the end of the Russian revolution, and the politically harsh decades of counter-revolution. The puny efforts of the vanguards that somehow resisted by swimming against the tide, in their effort to revise or safeguard the fundamental structures of revolutionary theory, have suffered, in part or in whole, under the weight of this counter-revolution.

The rest comes from isolation and the difficulties of establishing significant and lasting relationships with the class.

Very often isolation, whether voluntary or imposed by objective conditions, has accentuated both the extremes of passivity and its opposite: activism.

Although it may seem absurd and contradictory, idealism has many different faces, and different ways of expressing itself, but the method remains the same. The passive wait-and-see attitude which counts exclusively on the external situation to solve all our problems, is balanced out by blind voluntarism and wishful thinking which wants everything quickly and immediately. Both attitudes fall within the idealistic matrix, but at opposite ends.

If the party is a synthesis of doctrine and action, then the activist version puts the accent on the second. In this version idealism goes beyond the normal boundaries of activity which is appropriate to the demands of the situation, culminating in voluntarism, "whenever and wherever". By abstracting from the objective conditions, this voluntarism points to the party as the factor triggering economic and political demands. As such sees it as the "inventor" of struggles, as a subjective consciousness capable of undermining the existing social framework, regardless, or even against, the most basic laws which produce it.

Such an attitude, in addition to its lack of common sense, distorts how we interpret the dialectic between the economic situation and the class struggle, between the masses and the avant-garde, and eventually it opens the doors to opportunistic practices when expectations are regularly undermined by reality which, like it or not, is much stronger than any idealistic approach to the class struggle. The greater the external opposition, the more bone-headed activism insists on banging its head against the wall. The more organisational efforts are frustrated in a doomed attempt to revitalise struggles, the more these vanguards adopt the perspective of making political concessions in order to pursue a goal that is doomed to all round failure by the negative power of the situation.

How many times, especially in stagnant periods of the class struggle, have we seen so-called vanguards make hasty political retreats, both in tactics and by redefining "new" strategic objectives, in order to satisfy their activists by making "concrete" links with the world of work. Just as they thought they could find revolutionary solutions round every corner, they now discovered "revolutionary reforms" in new, why not, bourgeois areas for intervention, making the alleged and misunderstood "absence" of the working class a justification for all sorts of opportunistic ideological contortions.

In this sense, the bait is always ready to be taken. If the nature of the struggle and class consciousness are low, or almost non-existent, that's when voluntarist activists, rather than give up their anti-dialectical schemes, politically work at that low level of consciousness which they should, on the contrary, be trying to raise. As a last resort, they retrace their steps, but go off at a complete tangent, trying to do violence at all costs to the reality of the outside world.

Opportunism, in the economistic version tail-ends the obtuse wishful thinking of the terrorist version. They have opposite effects, but again share the same roots, seen lately(3) both in Italy and Europe with only minor differences in appearance and timing.

In conclusion, the idealistic approach, in all three versions looked at here, indifferentist, external or voluntarist, restricts or distorts the role of political vanguards, or reduces them to an appendage of the class struggle. Either it is seen as cultural factor, mythical and still outside the needs of the proletariat, or by exaggerated activism, with all its risks of opportunism, becoming in its voluntarist version, reformist.

The Mechanistic Approach to the Question of the Party

In its analysis and consequent intervention the mechanist approach always reduces the laws of the dialectic to a banal relationship between cause and effect. It removes the filter between a given economic situation and subjective human will. As the first takes shape, the latter will eventually submit to it, but the time and method are mediated by an infinity of other factors. Otherwise the classic relationship between structure and superstructure appears to be a mechanical relationship between cause and effect much closer to the laws of chemical experiments in the laboratory than to dialectical determinism.

In the mechanistic approach if a historically determined situation A is not present then situation B cannot exist, or, by inverting the terms of this mechanical interpretation of social development, outcome B occurs only if A is already present.

From a methodological point of view, this approach owes more to the Aristotelian than the Marxist school of thought. Nevertheless several times in the history of the workers’ movement this mechanistic interpretation has overtaken or even replaced the dialectical interpretation, claiming to represent its spirit in the most correct way.

In Marxist terms it is obvious that revolutionary events, class struggles, civil wars or other social events involving a movement of millions, do not fall down from the sky, but are the result of economic situations which are all the more crucial the greater their intensity and extension.

One of the pillars of Marxist revolutionary theory, which at one stroke rid the field of the ambitions of utopian socialism as the unrealistic demands of obtuse activism, demonstrates how every great social movement is simultaneously conditioning and conditioned by an economic "prius"(4) whose contradictory mechanisms end up, sooner or later, setting in motion irreconcilable interests that are the basis of every superstructural settlement or upheaval.

Maybe not all economic crises have triggered civil war or class struggle, but certainly there has never been social upheaval that did not originate from an increase in the contradictions in the world of the structure. In addition dialectical analysis has always taken account, always within the laws of economic determinism, the importance of the starting conditions, the initial political level of the class struggle, the acquired capacity of the bourgeoisie to manage, and then water down over time the depth and consequences of their own crises and the subjective responsive of workers, whether expressed with or without its political vanguard.

This is exactly the opposite of what happens in the analyses of both voluntarist and mechanistic idealism. In the first, the class struggle and the role of its vanguard are not linked to objective conditions but are arbitrary inflated by activist expectations, as if phenomena such as the readiness to the struggle, the raising of anti-capitalist demands, the awareness of means and ends, are more the consequences of an act of autonomous will, above or even outside "crude economic factors", rather than reflections of the latter.

For voluntarists it is enough just to have or at least to create conditions conducive to the class struggle. Economic demands as well the political demands, always exist everywhere in capitalist relations of production so that, regardless of the level of maturation of economic contradictions the role of the party can always be seen essentially as a promoter of fights, as an example of a practical consciousness, as a subjective condition, even when the system is not in a devastating crisis, or even when the level of the class struggle is very low. Indeed, the more unfavourable objective conditions become, the more voluntarism is forced to radicalise its demands to the point where they bear no relation to reality. It thus inevitably appears as a detached revolutionary tendency which does not know how to translate the acquisitions of social struggles into a concrete political programme.

In the second case, everything is down to the evolution of objective conditions. The crisis itself provides a favourable terrain for the birth or the intensification of the class struggle. This combination of the two phenomena, and only this, is the signal for the intervention of the party or even its birth, which otherwise would be unrealistic, dangerous, if not directly counter-productive.

Albeit at different levels, the mechanistic approach, in counter-revolutionary phase, denies the existence of any political space for a vanguard to operate in unless the latter does not act politically but merely becomes a circle of observers and commentators on social events without attempting to intervene in the limited places offered by the class struggle. Until the world of economic determination does not show signs of stress, there is nothing to that can be done. The slogan is "everyone go home and wait for better times."

It is obvious that the theoretical assumptions of both the "all at once" of the hyper-activists and "there's nothing to be done" of the “wait and see” tendency are respectively the result of too broad or too narrow a view of the correct dialectical interpretation of how the party functions in the course of the class struggle. It is equally obvious that the two tendencies, precisely because they are derived from the same original setting, contain the elements of truth, but not when they unilaterally emphasise either the subjective or objective conditions.

The mechanistic approach, to the party issue, limits its appearance and its intervention only to the time when the level of determination and consciousness of the class struggle, following the economic crisis, is at such a high level that it effectively poses the question of the final assault, or the conquest of power. This implicitly denies its vanguard role as the political product of the many partial and sectional impulses of the working class. Either it is the objective conditions that trigger the class struggle and determine, sooner or later, even it tactical-strategic aims, and push it to the threshold of power (at the most this suggests the party is a secondary accelerator and mere accessory to what occurs spontaneously, or if you prefer, is determined mechanically), or the crisis and the consequent revival of the class struggle, are necessary but not sufficient conditions for a revolutionary solution.

It is precisely the political presence of the party, that allows the spontaneity of the class to articulate its political aims, to transform a movement of revolt into a revolution. Otherwise, as has happened many times, the workers' struggles, originating in one sector and operating in no particular order, can only collapse in on themselves without shifting the balance of power against the class enemy by a single centimetre. The essential condition is that the party must co-exist and grow with the objective conditions and the consequent evolution of the class struggle. Otherwise it becomes a party of the last minute, which sets to work, or even worse, only appears after the right objective economic and subjective political conditions are openly expressed. At the very least it would risk being overtaken by events, always assuming that its wait-and see approach would give it enough time in the "ad hoc" situation to make itself known as the vanguard.

There is no shortage of deep and devastating economic crises in the history of class struggle, nor has the proletariat ever ceased to be the potential revolutionary subject; what it has often lacked was precisely the party either because it had been previously defeated by the forces of counter-revolution, or because it was not mature enough from a political point of view, or because it was told to wait for a more favourable time in the future. And when this came along it was taken by surprise. It was unprepared to play a leading role, and especially unable to establish in the space of "twenty-four hours" those essential ties with the class which allow it to play its political part.

Just as the class needs its party to express itself politically in a revolutionary sense, so the party needs its class content to exist and act. A proletariat that would go into a confrontation with the class enemy without political leadership would be doomed to defeat. Similarly a party unconnected to the class, or detached from its social content, might be a better guardian of revolutionary theory, might be the most perfect political machine, but it inevitably would have no bearing on a final solution. In order not to run into the latter situation, the vanguard should strive to establish contacts with the class even in less favourable phases. Put simply, we could say that the proletariat and the party will, in favourable situations, suffer the fate that they create for themselves in the counter-revolutionary period.

The mechanistic approach, on the contrary treats the party-class relationship in the same way as a physical phenomenon, underpinned by the laws of chance. This not only inhibits the party developing its slow and difficult organisational life in the stages preceding the onset of revolution, but also denies the proletariat its irreplaceable political weapon.

The schema: crisis – resumption of the class struggle – birth of the party, is both very limited from the dialectical point of view and dangerously impotent in tying together those endless threads that arise from the class struggle. If it were not put forward theoretically, as an abstract axiom, it would simply be discovered only when the situation allowed, in that brief, and often difficult to detect, space of time when the whole series of relations between class and party that are the basis for a revolutionary outcome, become clear.

The Role of the Party in the Class Struggle

First of all revolutionaries, the vanguard, and more specifically the class party can choose neither the time nor the conditions for intervention. Both are determined by the evolution of economic contradictions and their social repercussions. It is obviously bourgeois society in all its manifestations that determines and imposes on the class and its vanguard, not only the terrain, but also the manner of the confrontation. Just think of today’s systematic, scientific attack by the international bourgeoisie on the proletariat, on the basis of technological restructuring in all important fields of production. The fight against layoffs, dismissals, the reduction of labour costs in various ways, the super-exploitation of those who remain in the factory is: even the struggle to reduce working hours, started on the terrain imposed by the bourgeoisie. The economic crisis, the “shrinking” of the market, trade and financial wars, highlight this period. Just as in the previous period of economic and "wider" market expansion compatible marginal demands, within the framework of the "crumbs" of the growing capitalist accumulation process were possible.

Only the revival of class consciousness, assisted by the active presence of the class party, allows us to first stem and later overcome the conditioning of the bourgeoisie.

But to refuse a particular battleground because it is risky, difficult to work in politically, because it is better administered by capital, means the creation of assumptions which, in theoretically more favourable situations, will lead to the squandering of the chance to engage with the real evolving situation.

In the second place, the party is not just a factor of theory and will, but also the political instrument of the class struggle. Although the third connotation is implied in the first two, idealistic and mechanistic deformation don’t always take this into account.

When defining the political party as a weapon of the class struggle, we mean as a necessity and a tendency throughout the historic arc characterised by the permanence of capitalist relations of production, and not related to one particular aspect or moment of the class struggle. The term class struggle expresses a concept that has its material source in the antagonistic and irreconcilable conditions between bourgeoisie and proletariat, on the basis of the equally irreconcilable and antagonistic relationship between capital and labour, and not on any particular aspect or moment. From this the level of class struggle can obviously vary depending on the degree of development of economic contradictions, on the presence of the crisis, on the capacity of the bourgeoisie to manage it, on the consciousness of the working class, on its spirit of combativity, but the class struggle never ceases, so its political reference point should not fail either.

Even if the bourgeoisie is able to hold the upper hand against the proletariat, either through the mystifying role of social democracy, or through open political repression, by establishing emergency laws limiting or eliminating so-called civil and democratic rights, and by decapitating the proletariat of its most representative expressions, this does not mean that the class struggle no longer exists or is expressed at so low a level that there is no need to start some sort of opposition, albeit clandestinely. At this time all it means is that the bourgeoisie has made a successful offensive, and the proletariat a momentary retreat

The tiny minorities that were eventually able to escape from the strait-jacket of repression, don’t therefore have the right to theorise and practice their self-elimination due to the simple fact that the class struggle "is not there", and that therefore "there's nothing to do". Indeed, we could say that the future recovery of the class struggle will also be conditioned by what the tiny minorities have been able to accomplish politically in the openly counter-revolutionary periods.

It is the bourgeoisie’s task to squeeze the working class, both economically and politically, by cutting off its thinking head, by separating it from its party, and in its opposition to every political and economic demand. Revolutionaries, however few or many they are, however much or little impact they have on the course of the class struggle, must not give the bourgeoisie a hand in its task of wiping us out. By politically eliminating themselves, they finish off the task that state repression has only partially been able to carry out. Giving up even the task of slowly rebuilding, of infiltrating those small spaces which even the most repressive states allow, is the indispensable condition (but certainly not sufficient, we say this to the credulous of every stripe) for the speedier resumption of the class struggle in more mature times.

Where there are, even if minimal, possibilities of organisation and political work, it is necessary for the vanguard to work against the current, not only to renew the red thread, not only to keep immaculate “sacred principles” from degeneration, but also to strive to be a political reference point, however weak for however long, with respect to a class struggle that never ceases to exist even if only at low or very low levels.

The party, precisely because it is not different from the class, but is the most advanced and conscious part of it, and represents its political perspective at every stage of the confrontation with the class enemy, must not cease to play its role, on pain of self-elimination.

The parties and the vanguard can also disappear, as the period in which revisionism and counter-revolution decimated the revolutionary field in the second half of the twenties clearly demonstrated. It is one thing to succumb, fighting in the class struggle against the forces of counter-revolution, with all the negative consequences that follow, but its entirely another to bend to the situation by putting forward the notion that there is no need for a political reference point for the defeated class as it would be unnecessary or even harmful.

Such an approach would lead to a revision and correction of the slogan: “Proletarians of all countries, unite”, but only at times when the revolutionary assault is on the agenda whilst in normal day to day circumstance it’s “every man for himself, God for all”.

To the question on who or what can the class count when the explosion of capitalist contradictions pushes it onto the streets looking for some solution to its pressing problems as well as political leadership, which has not yet appeared or has been eclipsed, the stock answer is: the crisis itself! It’s a repeat of the mechanistic equation: crisis-recovery of the class struggle-birth of the party, as a spontaneous, natural phenomenon in the structure-superstructure relationship.

To make an initial conclusion, the anti-dialectical approach, whether in the idealistic or in the mechanistic version, does nothing but go beyond the upper and lower limits of the correct party-class ratio in the continuation of the capitalist relations of production.

It either does violence to the objective condition with all sorts of unrealistic activism, or it succumbs to them with an attitude of messianic waiting. The practical result of both is the impossibility of the creation or maintenance of organic relations with the class.

The dialectical approach that sees in the party elements of theory, method, of will, but is also the political creator in the evolution of the class struggle, independently of its historical or contextual levels, does not try to ignore reality, but submits tactically to it. It does not downgrade itself saying “there's nothing to be done”, but develops a line of action commensurate with the needs of the specific situation. It is not the usual happy medium between two extreme positions, but the dialectical overcoming of both.

FDPrometeo, 1985

Notes:

(1) Quoting Marx of The German Ideology

(2) In Italian the word we have translated as “wait-and-seeism” is “attendisti” (literally “sitters”). This was/is the position of Vercesi, Bordiga and most of the groups which take Bordiga as their starting point. “Maximalist” here refers to the fact that they just repeat the self-evident mantra of the need for a communist revolution and invite the class to join them.

(3) This document was written in 1984 when the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhof were still operative. Although not proletarian organisations their model of the elitist terrorist organisation claiming to speak on behalf of the class instead of the patient work of building a class conscious party has surfaced several times in proletarian history.

(4) Latin meaning “first” (“instigating cause” in this case)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

This whole article printed to 15 sides of A4, which I have read carefully all through, marking particular paragraphs, sentences, names of competing concepts, such as 'idealist', mechanistic' 'dialectical' as I went along. Trying to organise appropriately and effectively whilst in capitalist society dominated by bourgeois ideology is a challenging task, not forgetting the Boy Scouts motto, 'Be Prepared'! What worries me is that even when a necessary party is accepted by workers already convinced of its aims, the problem remains of convincing the mass of the proletarian public that, when made responsible for taking economic political power, they will have not just sufficient confidence, but enouogh initial knowledge to know what they are going to do, and be held responsible for doing it by working class, where they actually live. Socialism then communism won't just be somewhere else, but right here, in town or city. The notion of world wide plans for world communism are a long way down the red road, whereas as soon as the capitalists are overthrown 'here', workers and their children will need food, electricity and so on. Workers need to know that communist-led workers can and will produce and distribute all necessities at least as well as capitalist firms (though of course those don't do that so well anyway!) and soon better. Already workers do the production and distribution anyway, but managing it all is big step for many. I suspect that blaming the problems of post 1917 Russia on a lack of international supporting revolutions, whilst with some validity, is to disregard what was probably a more significant factor, that of insufficient knowledge of management, management of a new system of organising their own economy. I don't see how class struggle can become victorious in and from 2016 unless and until its intended local practical outcomes are clarified, not just in hyped ideological terms.

The reality is that today the CWO and the ICT are merely a few people who have correctly identified the need for a much more significant proletarian organisation. Until the class returns to a profound level of combativity and the revolutionary organisation becomes a powerful entity roted in the fighting class, then we are stuck with the task of patiently arguing for revolution, not actually building it. The construction of socialism is the task of the majority, not a few revolutionaries more than likely years away from any succesful outcome.

The key to local, and beyond, solutions is a social organisation gathering all members of the working class willing to participate - the soviet or council structure. When this arises, then we will be able to take stock of the resources available and begin the task of using them for society's benefit. This cannot be done years in advance. The terrain will change beyond recognition.

The immediate task is build the revolutionary organisation. Without which there will be no revolutionary class.

Or you could put it the other way round. when a minority of the class (but much wider than our reach now) starts to take up the agenda put before it (however feebly) by the revolutionaries then betwen them they create the revolutionary organisation.

Thank you, Stevein7 and Cleishbotham, for your perceptive responses of 17 & 18 Oct 2016. Frequently recently I see groups of 2 or 3 JWs standing by a mass of free pamphlets and booklets. I tell them that every word is a generalisation. I say that I do not want an after-life, but if I had to have one, what would I be doing and where would I be doing it ? ! They are organised, have both immediate and long-term perspectives and manage to bring some people together socially. Is any of that of any exemplary relevance to CWO , patiently arguing, more than likely years away from a successful outcome, when a minority starts to take up the agenda put before it ?. I once heard that there are two lessons from Auschwitz - The first chance is the best, and look after your feet ! (Useful for non-bourgeois voting !). On a bombsite in Manchester, at the end of WW2, a man stood selling a rationalist paper. In his hat band was a card with the words 'Atheism is the truth'. That sort of individual ideological activity will tend to be regarded as a cross between voices crying in the wilderness, irrelevant and or barmy or profoundly important, sooner or later or later, still, depending upon what sort of military or political apocalypse awaits 'their' (capitalist) and, someday, 'our' workers' planet, fit for children.

Broadly, but succinctly, the article says to me that those who wish to be revolutionaries, to contribute to changing, rather than an isolated comprehension of, the world ( to semi - plagiarise Marx) have to communicate with the working class, even when those elements willing to listen are soaked in ideology at odds with Marxist theory.

There is little point in a relationship where the theoretical aspect is ignored, equally there is little point to a debate restricted to the converted.

This is difficult. The presentation of theory to the wider class has to take into account the negative conditions which mentally restrict all but a few.

We are not here pursuing academic prestige, masters degrees, phds etc. We are not producing materials for professors to judge. We are making the case for revolution within a framework accessible to the non-specialists.

It may well prove to be beyond the capacity of many, However a balance of forces favouring the advanced pole of the class may be possible.

I've noted Steivin7's points of 2016-10-19,09:30. When occasion seems to provide scope for a chat with someone I happen to meet, as distinct from within an organised political meeting, after a few words it sometimes seems that much more could and should be made clear, but that it doesn't seem immediately feasible to get into deep and maybe long conversation, so it would be handy to have one or two leaflets in a pocket, so that something both manually and politically tangible could be imparted. (I have previously argued that it would be advantageous if leaflets could show the date when they are issued, which would aid sorting the amount of paperwork which tends to pile up). Leaflets, it seems to me, would be more readily used than the larger items, for instance Aurora and Revolutionary Perspectives. Printing off articles from CWO website is another answer, but those are not always of an introductory sort. Also, some instantly available reading matter gives the reader the chance to judge CWO by its text, rather than by how he or she might view the person issuing it.