You are here

Home ›In Austerity Britain

The First Step Forward is to Unite and Fight

The Crisis is Global

Now the election is over nobody is denying that capitalism faces a global crisis. In fact we are now being prepared by our rulers for an “era of austerity”. There was an initial shiver of panic amongst the ranks of the capitalist class as the financial meltdown of two years ago dramatically revealed the prospect of complete economic collapse. We’ve all heard the comparisons with 1929 and the Great Depression. Suddenly media pundits began to wonder if, after all, there was something in what Karl Marx had said about capitalism’s inherent tendency to crisis and self-destruction. Yet, despite the occasional expression of fear at the prospect of more widespread ‘social unrest’ and even the possibility of governments collapsing and political parties being forced out of government, the capitalists are generally far more nervous about what the financial markets have in store than about facing the sort of unified and determined working class resistance which could threaten their system altogether. Take the massive protests by workers in Greece to the austerity programme the government has announced at the behest of the IMF and the EU. As our tendency commented during the heat of the protests:

The Greek episode is a prime example of this phase of the crisis of international capital. The consequence of the financial “aid” of the European countries and the IMF, which have made available €110 billion over three years, are that the Athens government accepts a drastic austerity plan. The plan provides for the ending of the thirteenth and fourteenth month (where they exist) for public sector workers. A straight cut of 30% in wages and an avalanche of taxes on consumers. For the ECB (European Central Bank) the principal worry is to prevent speculation on the Euro, to support the countries most at risk of failure, to always hold up the value of the Euro, to eventually issue bonds which risk default. It has no worries about the world of labour other than to heap onto it all the sacrifices needed to revive the capitalist machine in such a way as to clear the debts produced by inept and corrupt speculative capitalists. (1)

== Sovereign Debt

If the Greek state was more incompetent than most at protecting its own finances from the ravages of financial speculation (the UK Treasury, for example, has been careful to issue long-dated bonds to try and avert a repayment of debt crisis), the fact remains that every state in Europe, along with the United States and virtually the whole of the ‘advanced capitalist world’ is becoming increasingly mired in debt as a result of the financial bail-outs and now the reduction in revenue from taxation as the recession bites. The state which had supposedly been rolled back for ever has been obliged to wade in and, one way or another, provide some form of ‘quantitative easing’ for a financial setup which would otherwise have collapsed. In the time-honoured capitalist crisis way, states have resorted to issuing government bonds and by so doing have compounded the debt crisis itself which is far from over. Now, not only are the pundits warning of a ‘double dip recession’ the financial markets are getting the jitters about the mounting pile of state or ‘sovereign’ debt. Quite simply, the fear that states themselves may be unable to pay back even the interest on their loans is pushing up the cost of borrowing for governments which, in turn, are obliged to offer higher rates of interest when they try to raise money by issuing bonds. This is what happened to Greece which found that the cost of borrowing on the financial markets had gone beyond its reach [see article Financial Crisis Engulfs the Eurozone in this issue]. Sometimes, as has happened recently with Germany, governments have been unable to raise a loan because there were not enough takers for their bonds. Meanwhile, every state is subject to the vetting of the credit rating agencies which grade companies and governments alike according to the state of their balance sheets as an indication of how likely they are or not to default on loans.

Just as with your credit card, the lower the credit rating of a country, the more difficult and expensive it is to borrow.

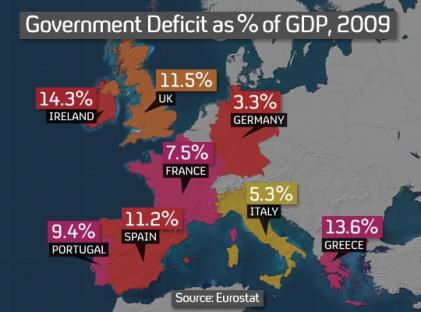

In the EU, apart from Greece, Spain and Ireland have already been downgraded by the likes of Fitch and Standard and Poor’s. Hence the overriding concern of governments everywhere to reduce the deficit as quickly as possible regardless, or despite, the social consequences for its citizens (or subjects in the case of the UK).

Before the general election the biggest worry for UK capital was that a hung parliament would cause ‘uncertainty’ – i.e. delay – in imposing measures to cut a deficit which currently stands at approximately 8 per cent of GDP. Why the hurry? Why not wait, in Keynesian fashion, for the economic upturn? The answer is that the Treasury and Bank of England are running to the call of the financial ratings agencies and the fear that UK capital might lose its ‘triple A’ credit rating which would also have the knock-on effect of undermining confidence in sterling. (The flimsiness of any upturn is another matter.) Predictably, therefore, the markets were reassured by the easy way UK politicians organised a cosy coalition government ready to get down to the onerous task of ‘reducing the deficit’.

On 12 May the Financial Times cheerfully recorded the markets’ reaction with the headline ‘Sterling and Gilts Soar’.

The Cuts

So, having reassured the markets for now, the task only remains for the politicians to determine where the axe is going to fall. So far Osborne’s announcement of an ‘immediate’ £6.2bn cut in government spending is going to mean between 30,000-50,000 jobs lost, much of this simply by not rehiring short-term contract workers.

(The UK’s workers are nothing if not flexible.) Everyone knows, however, that this is the tip of the iceberg. There are certainly more draconian cuts in jobs and services as well as taxation increases waiting to be announced in this month’s emergency budget, and probably still more in the autumn spending review. On the prospect for public sector job cuts, the Financial Times has yet again totted up the figures and concludes that

After the recession of the early 1990s, when the deficit was £50bn, rather than the current £156bn, almost 600,000 jobs went, as public sector employment fell from just under 5.4bn in 1991 to 4.8bn in 1998 before growing again. (2)

But this is no ‘ordinary’ downturn.

Capital is facing the deepest crisis in its history and the outlook for the working class is bleak both in the short and long term. As we pointed out in an earlier issue,

Both main political parties are looking to cut £35 billion off government spending in 2011. They can only do this by hitting at services to the most vulnerable. One straw in the wind is that the 2.6 million on disability benefit will be forced to make themselves available for some work or lose their benefit. (3)

Sure enough Iain Duncan Smith, Work and Pensions Secretary, has already promised to press ahead in the autumn with a review of the work capability of all people claiming any sort of invalidity benefit. This, combined with promises to apply sanctions on claimants who refuse ‘job opportunities’ is a clear message of what is immediately in the offing. However, even if Duncan Smith himself is not sure where his review is going to take him, it is clear that the whole principle and framework of a universal benefits system that has gradually been eroded over the years is due to be replaced by what he describes as a single withdrawal rate for all benefits. Above all, the government wants to ensure that it is no longer ‘worthwhile’ for anyone to claim benefits rather than accept the lowest paid work. Inch by inch the principle of ‘less eligibility’ which underpinned the New Poor Law of the nineteenth century (i.e. the principle that workhouse conditions should be made less preferable than those of the lowest paid labourer) is replacing the principle of universal welfare. As it is the full annual basic state pension stands today at £5,078, an impossible sum on its own to live on. The announcement that after 2016 for men and 2010 for women the state pension age will be sixty-six is an irrelevance for most people who will have to work longer in any case in the increasingly vain hope of building themselves a pension pot large enough to live on.

The fact is that wage workers are facing not just a period of temporary cuts and a little belt tightening, they are up against a system which is now decades into a severe crisis, whose driving force of accumulating new value based on the unpaid labour of the working class is being paralysed by the inexorable process of capitalism’s intrinsic law of the falling rate of profit. As the Financial Times recently bemoaned in an editorial,

In fact it can often feel as though there is no longer anywhere in the world for investors to safely and profitably sink their money. (4)

Of course this does not stop capitalists from seeking new ways of making a profit –when push comes to shove it does not matter to them whether this means transferring production to areas with rock bottom wages. And when it is more profitable, in money terms, (because capitalists themselves do not distinguish between value expropriated from wage workers and nominal financial values based on bits of paper) to simply ‘invest’ in the financial markets than to employ workers in productive labour financial speculation comes to the fore as it has done with a vengeance today. Yet the more capital is directed to financial speculation which does not generate new value but which, on the contrary, creates a massive virtual world of parasitic fictitious capital representing nothing at all except the overblown value of an initial real asset (such as a house), the more the system as a whole is weighed down by its burden of debt. This is a situation which is wholly due to capitalism. It is not the responsibility of the working class. Yet, it is workers who are paying and - so long as this system exists - are expected to paythe price.

Capitalists Smell Danger Ahead

Perhaps, though, the capitalists themselves are sensing danger ahead.

This particular stage of the crisis is by no means over. (The capitalist world as a whole still has $30,000bn of outstanding credit default swaps waiting to implode; in the UK the pundits are worried about the £50bn of commercial property loans which are in trouble, 70 per cent of them due to mature in the next five years.) However, there are only so many attacks that can be made without provoking widespread anger and resistance; without the myth that ‘we are all in this together’ breaking down.

Already capital is sensing the need to call on the unions to control the working class, to divide and limit any resistance. For instance, the Court of Appeal’s overturning of the previous injunction against the BA strike has reversed a five year trend of bosses calling on the courts to stop a strike (43 cases, 90 per cent of them won by the bosses).

At the same time there are growing calls to limit the astronomical personal incomes as well as the speculative activities of the financial sector (as if this would make the cuts more bearable).

In Germany Angela Merkel has already brought in rules against ‘short selling’ and here, despite Cameron’s own instinct not to increase the rate of capital gains tax, even the FT is arguing that bankers’ bonuses should be taxed ‘as normal income’. - Even the FT is balking at a situation where (in 2008) the top 10% of City bankers got 30% of total national wages. One writer, John Kay, bluntly admitted in his column on 2nd June,

It is shaming when hedge fund managers pay a lower rate of tax than the people who clean their offices.

This followed a comment in the Lex Column of the previous day’s issue which is worth quoting at length:

A year ago, as political leaders sought intellectual support for stimulus spending, John Maynard Keynes, the great economist, returned to fashion. It may now be time to brush off those dusty copies of Karl Marx as well. The bail-out of the financial system and the need to appease bond markets are largely problems of capital. Labour, meanwhile, bears the brunt of unemployment, depressed wages and, eventually, higher taxes. As the reaction of workers in Greece to that country’s ferocious austerity measures has shown, attempts to deal with public debt loads can cause tempers to fray.

There could hardly be a more striking illustration of how class conscious these spokesmen for capital are.

Apart from putting down workers’ legitimate anger at the threat to their livelihoods as a bout of bad temper, this shows that the advisers and opinion shapers of the ruling class are well aware that the class struggle is by no means a thing of the past. They know that a certain amount of resistance is inevitable. However, in the spirit of the one- nation Tory, they want to believe that there is a national interest that everyone shares above class interests; that capitalism, if managed properly, can provide prosperity for all.

So, in the next breath, the piece continues,

The split between capital and labour may well be a false distinction. Imploding banks are bad for everyone and businesses need funding to expand and hire. … Bans on short selling and measures to curb speculative trading already suggest a mood of anger at unfair profiteering. There are legitimate arguments both for and against taxing capital at a higher rate, largely revolving around what encourages entrepreneurship. Taxes have to rise, though, and capital has a fight on its hands.

In other words, the mainstream spokesmen of capital are - albeit reluctantly - joining in the calls of the capitalist left to tax the rich and clampdown on financial capital. It is part of the growing argument that there are good capitalists and bad capitalists, the good ones being the ‘entrepreneurs’ who create real value.

This not only ducks the question of why financial speculation has taken over in the first place, calling for laws against speculators could be a dangerous diversion for any incipient resistance movement by the working class. This will not be the only pitfall workers face in the months and years ahead. One thing is certain, though, to paraphrase the words of David Cameron, workers’ living standards and whole way of life are under attack as never before. The battles which lie ahead will not be worth fighting if they do not lead to the creation and strengthening of a strong political vanguard which illuminates the way forward for workers, not just here in Britain but throughout the world.

The first step on that road will be for workers to recognise once again that their own interests cannot be reconciled with those of capital.

ER(1) Statement by the Internationalist Communist Tendency issued May 2010, available on our website.

(2) 25.5.10 ‘30,000 Job Losses Seen As Tip of Iceberg’.

(3) ‘Time to Turn the Spectre into Reality’, Revolutionary Perspectives 49.

(4) Editorial, 5-6 June this year. In fact the piece went on to recommend investors to sink their money in Brazil.

Revolutionary Perspectives

Journal of the Communist Workers’ Organisation -- Why not subscribe to get the articles whilst they are still current and help the struggle for a society free from exploitation, war and misery? Joint subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (our agitational bulletin - 4 issues) are £15 in the UK, €24 in Europe and $30 in the rest of the World.

Revolutionary Perspectives #54

Summer 2010 (Series 3)

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Anti-CPE movement in France

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.