You are here

Home ›NWBCW and the "Real International Bureau" of 1915

The International Socialist Commission was created in 1916 after Zimmerwald, after the existence of a “real international bureau”(1) created in 1915 by the Italian Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland.

The war raging anew in Europe between the great imperialist powers – Russia on the one side and NATO, the USA and Ukraine on the other – leads us to recall the action of the internationalists during the First World War.

It seems pertinent to note some of the revolutionaries’ points of action.

- We are faced with impatient people who accuse us of not doing much and of not responding to the current situation with the required seriousness. We hear these recriminations, but the current proletarian milieu is even tinier and more splintered than in August 1914. What’s more, it took a year of travelling, discussion and dithering back then before an international conference was finally convened at Zimmerwald followed by a supplementary one for a radical “left” to emerge at Kienthal posing real political challenges. What can we tell them now but to get to work?

- We are faced with tight-lipped curmudgeons carefully selecting the few real internationalists in the word without any clear political criteria. This is not the time for picking and choosing among those who oppose the war on the basis of a revolutionary programme. In the first place, just as before Zimmerwald, all revolutionary and internationalist energies are worth the effort of regroupment. But more than this, the example of France was significant with the Committee for the Resumption of International Relations (Comité pour la Reprise des Relations internationales - CRRI), which led the most activity and was the heart of the workers’ opposition to the war. From its inception it regrouped revolutionary syndicalists, as well as militants of the Socialist Party, the section of the International which had failed. Indeed, the raison d'être of the CRRI was its opposition to the war and to the Sacred Union, to bring together different opponents of them, having come from syndicalism, socialism and anarchism.

This is also the raison d'être of the NWBCW committees. We will see as time goes by who will be the most determined and who will provide the appropriate answers for the future. Can we draw any useful lessons from the Zimmerwald movement? - The lessons of history are one thing, the reality is always different. We have often observed that imperialist wars are great accelerators of history. 1914 was a huge break in the evolution of the world and the labour movement. This is why, even today, we must remain very open.

Looking at the labour movement itself two facts immediately jump out:

a) In 1914 there was a mass movement in some countries such as Germany, Russia, Italy, the Balkans and Great Britain. The working class was very militant.

b) Today we are emerging from 45 years of decline in the class struggle and the recomposition of the working class. The bourgeoisie had been on the offensive since Reaganomics and globalisation.

It is in the face of these difficulties that we must know how to use the consequences of the war to bring together the political and the economic in order to provide a spark for a more conscious struggle of the working class in the widest sense. This fight is important if we don't want it to fall into reformism.

We are therefore at the very start of the recomposition of the labour movement. If we want to repeat historical analogies, we must emphasise that we are therefore well ahead of Zimmerwald with our proposal for NWBCW committees. It is only when we have clearly highlighted the consequences of the war that the road to discussions between the most conscious militants (that is to say, revolutionaries) will be open, in order to prepare the ground for the International.

A Few Lessons of the Zimmerwald Movement

The declaration of war in August 1914, and the betrayal of the International, stunned socialists, syndicalists and anarchists alike. It would be some time before the first reactions against the World War would emerge

1. The Beginnings of Socialists’ Actions against the War

a) After September 1914, all the socialist parties of the neutral countries attempted to renew international links interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. The very first initiative came from the Socialist Party of America, but it was left unanswered due to its relative weakness and the party’s isolated geographic position.

It was in Lugano that the first international socialist conference was organised on 27 September 1914, which declared itself explicitly against the war. Naturally, it was a mere bilateral meeting of the socialist parties of the two neighbouring neutral countries, but already this “Southern Group” formed the first core of what was to become the Zimmerwald movement.

Morgari proposed the creation of a "real international bureau, but a temporary one, which would take up action immediately and which would be based in Switzerland."(2) The international actions of the Swiss and Italian socialists quickly took on a more radical dynamic. This was especially the case after Italy entered the war in May 1915. Unlike the socialist parties of other large countries in Western Europe, the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) remained opposed to Italy entering the war, and continued its efforts for a revival of socialist internationalism.

b) The International Socialist Congress of Copenhagen held 17-18 January 1915 was the first attempt to regroup socialists, at which the socialists of the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands participated but the Italians refused to participate, as they thought it was a German initiative. This first congress was still full of illusions in regrouping the socialists of all countries to defend peace. It began on Sunday 17 January 1915. The Swedish delegates were Branting and Ström for the SAP(3), Herman Lindvist and Ernst Södeberg for the LO.(4) The Danish delegation consisted of TH Stauning, F Borgbjerg, Sigvald Olsen and Carl F Madsen, the Norwegian one of Magnus Nielsen, J Vidnes, Ole C Lian and Sverre Iversen. Last but not least, the Social Democratic Workers’ Party in the Netherlands sent P Troelstra, H van Jol, Vliegen and Wibaut. Apart from these 16 delegates, there were a few more Danish socialists, as well as de Roode, the editor of the Dutch socialist journal Het Volk, and Anna Leepa, a representative of the Bund. On the Sunday, Stauning, who welcomed the delegates on behalf of the Danish Party, declared that the American and Swiss representatives “were not able to attend”, nor Morgari, the secretary of the Italian Socialist Party.(5) Lenin, for his part, had written to Shlyapnikov(6), then in Copenhagen, telling him “not to attend the Congress”, informing him that “the Swiss comrades would not be going either”.

The agenda was as follows:

- Action in favour of peace

a) Request to governments

b) Peace programme of Social Democracy - Propositions from Switzerland and the USA

a) Plans for conferences of the neutral states

b) Plans for convening a congress of the socialist parties of the neutral states

This first conference reminded socialists to work for peace; as yet there was no revolutionary position although the global imperialist war posed the question of communist revolution.

A commission composed of Branting, Nielsen, Stauning and Troelstra was given the task of composing the three resolutions. The first reminded social democratic workers “and particularly those in the belligerent countries” of the principles of the International that had already been declared at its own Copenhagen Congress in 1910, and decried “the violation of international law to the detriment of Belgium”. For the second, the Congress demanded that the social democratic parties of the neutral states invite their governments to mediate, separately or together, for peace between the belligerents (our own emphasis; we see here the pacifist position of the delegates of the Congress). Finally, in the third resolution, the Congress denounced the arrest of the five members of the Russian Duma who had written a report for that Congress.

These efforts to reconstitute the International were in vain. So on 26 April, the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland invited all the representatives from the neutral countries to a large conference set to take place in Zürich on 30 May. They still hoped that the International Socialist Bureau (BSI) would take up the task there of convening the delegates; however, they declared that in light of the latter’s failure to do so, they would take the initiative themselves.

For several socialist leaders, it was the task of the BSI to call a conference of the neutral elements. Moreover, during the Copenhagen Congress, the Scandinavian and Dutch attendees also came out in favour of the EC of the BSI calling a socialist conference for peace.

c) Other Actions and International Conferences. A “House of the People” had existed in Bern since 1893, and it was here that the Third International Socialist Women's Conference (25-27 March 1915) and the International Socialist Youth Conference (5-7 April 1915) took place, both of which took explicit anti-war positions.(7) The initiative of the PSI, the SDP of Switzerland and Morgari gained momentum after these two conferences.

In April 1915, Morgari, following consultation with the Swiss socialists, travelled to France on behalf of the PSI. Morgari was part of the right wing of the party, but was a pacifist. He met with the Belgian socialist leader Émile Vandervelde, the president of the EC of the BSI. His proposals for an international reunion were categorically rejected by Vandervelde. In Paris, Morgari discussed with the Menshevik Julius Martov, who convinced him of the necessity of a conference of anti-war socialists independent of the BSI. This idea was reinforced by the fact that at the same time as these discussions were taking place, a manifesto was written by the anti-war opposition of the SPD. This manifesto made its way to France and inspired the French opposition to the war. It also found audiences in Trotsky, Victor Chernov, and among other French anti-war socialists around Merrheim and Pierre Monatte. From Paris, Morgari went to London, where the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the British Socialist Party (BSP) expressed their interest in a conference of anti-war socialists. At a conference of the party on 15-16 May, the PSI finally approved a conference of all the socialist parties and groups opposed to the war.

d) Preparatory Work for Zimmerwald. This time, the “House of the People” in Bern housed the preparatory meeting for the Zimmerwald Conference on 11 July 1915.(8) Initially the Bolsheviks and other groups of the left were not invited to the preparatory conference in Bern which was limited to parties that were members of the BSI. Then, seven delegates met at the organisational meeting: the Bolshevik Grigory Zinoviev; the Menshevik Pavel Axelrod; Angelica Balabanoff and Oddino Morgari from the PSI; Adolf Warski from the SDKPiL, Maksymilian Horwitz from the PPS-L; and Robert Grimm from the SDP of Switzerland. Only the Italians came from abroad – the other participants all lived in Switzerland.

The meeting opened with discussions on whom to invite to the meeting. Grimm proposed that all socialists opposed to the war and in favour of a revival of class struggle should be welcome. Zinoviev demanded that participation be limited to the revolutionary left. Ultimately, the meeting decided to invite all socialists explicitly opposed to the war, including the French and German anti-war centrists such as Haase and Kautsky. Zinoviev also called for various groups on the left to participate, but the proposal was rejected again. The meeting decided to limit participation to members of the Second International, but fortunately this restriction was not applied in the end since the syndicalists also participated.

Robert Grimm and others ended up convincing key socialists opposed to the war to participate in the secret international conference which was to take place on 5-9 September in Zimmerwald. As well as the Swiss delegates Fritz Platten, Charles Naine and Carl Vital Moor, the delegates from twelve countries included Lenin, Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek, Georg Lebedour (from Germany), Alphonse Merrheim (France) and Giacinto Menotti Serrati (Italy). Grimm benefited from the fact that he had prematurely opened the columns of the Berner Tagwacht(9) to contributions from all dissident socialist currents and that as a citizen of a neutral country, he could act on both sides of the front.

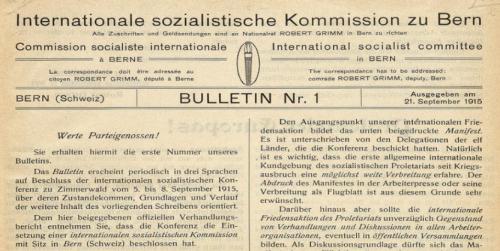

The participants adopted a manifesto which, criticising the support that the official socialist parties had given to the war, called for a struggle against the war and a break from the Sacred Union. This text, notably because it held the signatures of the German, French, Italian and Russian socialists, had a great impact. The conference created an International Socialist Commission (ISC). For the majority of its supporters, the Zimmerwald movement was to coordinate the activities of the socialist opponents of the war with a bulletin (see Issue 1 above).

2. The Anarchists

So where were the anarchists in this general debacle? Had the disarray that had hit all revolutionaries spared the anarchists? It would be vain and false to claim that they had entirely escaped.

In France, Sébastien Faure (who refused to add his signature to those of his comrades – such as Kropotkin and Jean Grave – to the Manifesto of the Sixteen which supported the Sacred Union) composed, with the militants who had remained anti-war, a counter-manifesto, which would be whitewashed by censors.

To the international conferences of leaders who dispose of peoples as docile herds according to their fancy, we believe we must oppose an international conference of workers of the whole world. Already in September 1915, in Zimmerwald, a first attempt was made at this, and at the time we applauded this preliminary effort. But this was but a first draft. This effort will be renewed, and must reach the magnitude that the gravity of the circumstances demands. The organisations of workers of all countries should henceforth make haste to convene a global congress of the proletariat, whose aim first and foremost must be to demand an end to hostilities and the immediate and definitive disarmament of the nations.

He continued to clandestinely distribute leaflets that would reach as far as the trenches. Malatesta wrote:

The line of conduct for Anarchists is clearly marked out by the very logic of their aspirations. The war ought to have been prevented by bringing about the Revolution, or at least by making the Government afraid of the Revolution. Either the strength or the skill necessary for this has been lacking. Peace ought to be imposed by bringing about the Revolution, or at least by threatening to do so. To the present time, the strength or the skill is wanting.(10)

This position resembled that of the revolutionary Marxists, who understood that only a revolution could bring peace.

In addition, the Swiss anarchist journal Il Risveglio(11) wrote on Zimmerwald and the divergences between its participants:

Hence the socialists themselves are not all satisfied by Zimmerwald. How could we be, without renouncing all the richness of our ideas, without adopting a tactic which has reduced socialism and syndicalism to total impotence? The International has risen

It goes on to specify that there were two main attitudes among the anarchists: those who supported Zimmerwald, and those who didn’t. Il Risveglio was among the latter. In a later article, it stated that “the group Libertario in Italy and the group Temps Nouveaux in Paris have joined. We continue to believe that they simply wanted to celebrate the moral significance of the conference, in spite of everything, men of various opposing countries.”(12). For Il Risveglio, Zimmerwald remained a conference of statists and parliamentarians…

Notwithstanding the position of Il Risveglio, it is clear that revolutionaries of all sorts of political positions were forced to either join the Zimmerwald movement or take a position in relation to it. The situation was too serious not to join the only important international initiative. We believe that the NWBCW initiative conforms to the principles of the Zimmerwald Left. It's up to us to keep the spirit of them in order to make them bear fruit in today's world.

3. Insufficient Results at Zimmerwald, Overtures to the Future…

Naturally, all the participants had to make concessions, and the results were weak in relation to the ongoing massacre on the battlefields, the desperation of families and the gravity of the global situation. However, after the collapse of the main workers’ organisations in the world, Zimmerwald was a step forward, a window of hope in the bloody imperialist butchery.

We know how the conference ultimately united on a text of compromise, the “Zimmerwald Manifesto”. This is why Lenin, Zinoviev, Radek, Höglund and Nerman signed the declaration of the Zimmerwald Left: “We accept the Manifesto because we see it as a call to struggle, and in this struggle, we wish to march hand in hand with other groups of the International”, declared the signatures of the minority, but “the accepted Manifesto does not satisfy us completely”.(13) Despite vehement protests against the war “the Centre triumphed once more at Zimmerwald” and the Conference “yielded no revolutionary slogan”.(14) On behalf of the social democratic youth organisations of Sweden and Norway, Höglund and Nerman therefore promised the Zimmerwald Left (created by Lenin at the end of the Conference) financial aid(15) equal to that which the ISC set up at Bern would receive.

Bern was designated at Zimmerwald as the seat of the ISC. Robert Grimm was the president of the latter. Balabanoff functioned within it as an interpreter and secretary, Morgari represented the PSI within it, and Naine the RSDLP. It was also at Bern’s “House of the People” that the meetings of the expanded ISC took place between February and May 1916. At the end of April 1916, the ISC organised the second conference at Kienthal. Grimm declared that the role of the ISC would confine itself to the publication of an international bulletin and the coordination of propaganda against the war, and that it would cease its activity so that the BSI would take it up. It was still under the illusion that the International would resume its normal activities.

These results were already a success. They would bear fruit in time; without them what followed would certainly not have been possible. The organisations still contained right wings, centres and left wings. The left would develop until Kienthal and beyond. Its action would accompany the Russian and German Revolutions, the end of the war and the creation of a new International.

The time has now come to acknowledge our responsibilities in the face of a world that has been transformed profoundly by the entry of the great imperialist powers into a war in Europe, which has as its ultimate aim the isolation and suffocation of China. We are entering into a new and long sequence of events; our efforts against the war and, on the other hand, for class war will have to endure for many years. Consequently:

- No discouragement, our fight will be difficult. We will have to fight to convince as many comrades as possible to join us and to spread our ideas to destroy capitalism once and for all and with it all states which sow death and misery;

- In this herculean struggle we cannot afford to divide ourselves from those who are internationalists and revolutionaries, and who would like to join with us.

We have a better world to win.

M.O.Bilan & Perspectives

July 2022

Notes:

Image: Issue 1 of the Bulletin of the ISC, 21 September 1915, which contained the French, German and English versions of the manifesto adopted by the delegates at the Zimmerwald Conference.

(1) Morgari's proposal, see minutes of the meeting. Obviously this proposal was made due to the bankruptcy of the BSI of the Second International – Source: Jules Humbert-Droz: L’origine de l’Internationale Communiste – De Zimmerwald à Moscou. Éditions la Baconnière, Neuchâtel, 1968. Pages 91-99.

(2) A transcript of the conference can be found at: Conférence des deux partis suisses et italiens: Procès-verbal des discussions – [Fragments d'Histoire de la gauche radicale] (archivesautonomies.org)

(3) Social Democratic Workers' Party of Sweden, founded in 1889 (Sveriges Socialdemokratiska Arbetareparti or SAP).

(4) Confederation of Swedish Unions (Landsorganisationen – LO).

(5) See, Le parti social-démocrate suédois et la politique étrangère de la Suède, 1914-1918, chapitre: Le conflit à l’intérieur du parti, p. 152-169 (by Jean-Pierre Mousson-Lestang, Editions de la Sorbonne, 1989).

(6) He had returned to Russia clandestinely in April 1914 under a French identity (Jacob Noé); at the start of the war he had to leave Russia because all able-bodied French were engaged in the army. At the end of September 1914, he therefore left for Scandinavia with a mandate provided by the St. Petersburg Committee and by the Bolshevik fraction of the Duma, which indicated that he was their official representative abroad. At that time Shlyapnikov did not entirely agree with Lenin. He wanted to find a solution so that the slogans of fighting against his own bourgeoisie in Russia would not favour German imperialism too much.

(7) See the resolution of the Conference in Berner Tagwacht, issue 88, 17 April 1915: Compte-rendu officiel de la conférence – [Fragments d'Histoire de la gauche radicale] (archivesautonomies.org)

(8) Zinoviev’s Report: Conférence préliminaire à Berne – Zinoviev – [Fragments d'Histoire de la gauche radicale] (archivesautonomies.org)

(9) The role of the Berner Tagwacht was important for the revolutionaries:

"our forces were still weak and scattered, but the precise indications that we gave our visitor enabled him to give an exact and faithful overview of the real situation in France, and it was the Berner Tagwacht that spread the news across all the countries, particularly in Germany where it was particularly important that people knew the truth." (Alfred Rosmer in Le mouvement ouvrier pendant la guerre. De l'union sacrée à Zimmerwald, Paris, Librairie du Travail, 1936, p. 369).

(10) Article from April 1916 in the English anarchist journal Freedom.

(11) "On Zimmerwald", issue 426, 1 January 1916 (translation from Italian our own).

(12) “Why we are Zimmerwaldians”, issue 443, 9 September 1916 (translation from Italian our own).

(13) Cf. : marxists.org.

(14) Cf. : Ture Nerman in Berner Tagwacht, 5 September 1935 : archivesautonomies.org

(15) op. cit.

Start here...

- Navigating the Basics

- Platform

- For Communism

- Introduction to Our History

- CWO Social Media

- IWG Social Media

- Klasbatalo Social Media

- Italian Communist Left

- Russian Communist Left

The Internationalist Communist Tendency consists of (unsurprisingly!) not-for-profit organisations. We have no so-called “professional revolutionaries”, nor paid officials. Our sole funding comes from the subscriptions and donations of members and supporters. Anyone wishing to donate can now do so safely using the Paypal buttons below.

ICT publications are not copyrighted and we only ask that those who reproduce them acknowledge the original source (author and website leftcom.org). Purchasing any of the publications listed (see catalogue) can be done in two ways:

- By emailing us at uk@leftcom.org, us@leftcom.org or ca@leftcom.org and asking for our banking details

- By donating the cost of the publications required via Paypal using the “Donate” buttons

- By cheque made out to "Prometheus Publications" and sending it to the following address: CWO, BM CWO, London, WC1N 3XX

The CWO also offers subscriptions to Revolutionary Perspectives (3 issues) and Aurora (at least 4 issues):

- UK £15 (€18)

- Europe £20 (€24)

- World £25 (€30, $30)

Take out a supporter’s sub by adding £10 (€12) to each sum. This will give you priority mailings of Aurora and other free pamphlets as they are produced.

ICT sections

Basics

- Bourgeois revolution

- Competition and monopoly

- Core and peripheral countries

- Crisis

- Decadence

- Democracy and dictatorship

- Exploitation and accumulation

- Factory and territory groups

- Financialization

- Globalization

- Historical materialism

- Imperialism

- Our Intervention

- Party and class

- Proletarian revolution

- Seigniorage

- Social classes

- Socialism and communism

- State

- State capitalism

- War economics

Facts

- Activities

- Arms

- Automotive industry

- Books, art and culture

- Commerce

- Communications

- Conflicts

- Contracts and wages

- Corporate trends

- Criminal activities

- Disasters

- Discriminations

- Discussions

- Drugs and dependencies

- Economic policies

- Education and youth

- Elections and polls

- Energy, oil and fuels

- Environment and resources

- Financial market

- Food

- Health and social assistance

- Housing

- Information and media

- International relations

- Law

- Migrations

- Pensions and benefits

- Philosophy and religion

- Repression and control

- Science and technics

- Social unrest

- Terrorist outrages

- Transports

- Unemployment and precarity

- Workers' conditions and struggles

History

- 01. Prehistory

- 02. Ancient History

- 03. Middle Ages

- 04. Modern History

- 1800: Industrial Revolution

- 1900s

- 1910s

- 1911-12: Turko-Italian War for Libya

- 1912: Intransigent Revolutionary Fraction of the PSI

- 1912: Republic of China

- 1913: Fordism (assembly line)

- 1914-18: World War I

- 1917: Russian Revolution

- 1918: Abstentionist Communist Fraction of the PSI

- 1918: German Revolution

- 1919-20: Biennio Rosso in Italy

- 1919-43: Third International

- 1919: Hungarian Revolution

- 1930s

- 1931: Japan occupies Manchuria

- 1933-43: New Deal

- 1933-45: Nazism

- 1934: Long March of Chinese communists

- 1934: Miners' uprising in Asturias

- 1934: Workers' uprising in "Red Vienna"

- 1935-36: Italian Army Invades Ethiopia

- 1936-38: Great Purge

- 1936-39: Spanish Civil War

- 1937: International Bureau of Fractions of the Communist Left

- 1938: Fourth International

- 1940s

- 1960s

- 1980s

- 1979-89: Soviet war in Afghanistan

- 1980-88: Iran-Iraq War

- 1982: First Lebanon War

- 1982: Sabra and Chatila

- 1986: Chernobyl disaster

- 1987-93: First Intifada

- 1989: Fall of the Berlin Wall

- 1979-90: Thatcher Government

- 1980: Strikes in Poland

- 1982: Falklands War

- 1983: Foundation of IBRP

- 1984-85: UK Miners' Strike

- 1987: Perestroika

- 1989: Tiananmen Square Protests

- 1990s

- 1991: Breakup of Yugoslavia

- 1991: Dissolution of Soviet Union

- 1991: First Gulf War

- 1992-95: UN intervention in Somalia

- 1994-96: First Chechen War

- 1994: Genocide in Rwanda

- 1999-2000: Second Chechen War

- 1999: Introduction of euro

- 1999: Kosovo War

- 1999: WTO conference in Seattle

- 1995: NATO Bombing in Bosnia

- 2000s

- 2000: Second intifada

- 2001: September 11 attacks

- 2001: Piqueteros Movement in Argentina

- 2001: War in Afghanistan

- 2001: G8 Summit in Genoa

- 2003: Second Gulf War

- 2004: Asian Tsunami

- 2004: Madrid train bombings

- 2005: Banlieue riots in France

- 2005: Hurricane Katrina

- 2005: London bombings

- 2006: Comuna de Oaxaca

- 2006: Second Lebanon War

- 2007: Subprime Crisis

- 2008: Onda movement in Italy

- 2008: War in Georgia

- 2008: Riots in Greece

- 2008: Pomigliano Struggle

- 2008: Global Crisis

- 2008: Automotive Crisis

- 2009: Post-election crisis in Iran

- 2009: Israel-Gaza conflict

- 2006: Anti-CPE Movement in France

- 2020s

- 1920s

- 1921-28: New Economic Policy

- 1921: Communist Party of Italy

- 1921: Kronstadt Rebellion

- 1922-45: Fascism

- 1922-52: Stalin is General Secretary of PCUS

- 1925-27: Canton and Shanghai revolt

- 1925: Comitato d'Intesa

- 1926: General strike in Britain

- 1926: Lyons Congress of PCd’I

- 1927: Vienna revolt

- 1928: First five-year plan

- 1928: Left Fraction of the PCd'I

- 1929: Great Depression

- 1950s

- 1970s

- 1969-80: Anni di piombo in Italy

- 1971: End of the Bretton Woods System

- 1971: Microprocessor

- 1973: Pinochet's military junta in Chile

- 1975: Toyotism (just-in-time)

- 1977-81: International Conferences Convoked by PCInt

- 1977: '77 movement

- 1978: Economic Reforms in China

- 1978: Islamic Revolution in Iran

- 1978: South Lebanon conflict

- 2010s

- 2010: Greek debt crisis

- 2011: War in Libya

- 2011: Indignados and Occupy movements

- 2011: Sovereign debt crisis

- 2011: Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster in Japan

- 2011: Uprising in Maghreb

- 2014: Euromaidan

- 2016: Brexit Referendum

- 2017: Catalan Referendum

- 2019: Maquiladoras Struggle

- 2010: Student Protests in UK and Italy

- 2011: War in Syria

- 2013: Black Lives Matter Movement

- 2014: Military Intervention Against ISIS

- 2015: Refugee Crisis

- 2018: Haft Tappeh Struggle

- 2018: Climate Movement

People

- Amadeo Bordiga

- Anton Pannekoek

- Antonio Gramsci

- Arrigo Cervetto

- Bruno Fortichiari

- Bruno Maffi

- Celso Beltrami

- Davide Casartelli

- Errico Malatesta

- Fabio Damen

- Fausto Atti

- Franco Migliaccio

- Franz Mehring

- Friedrich Engels

- Giorgio Paolucci

- Guido Torricelli

- Heinz Langerhans

- Helmut Wagner

- Henryk Grossmann

- Karl Korsch

- Karl Liebknecht

- Karl Marx

- Leon Trotsky

- Lorenzo Procopio

- Mario Acquaviva

- Mauro jr. Stefanini

- Michail Bakunin

- Onorato Damen

- Ottorino Perrone (Vercesi)

- Paul Mattick

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Lenin

Politics

- Anarchism

- Anti-Americanism

- Anti-Globalization Movement

- Antifascism and United Front

- Antiracism

- Armed Struggle

- Autonomism and Workerism

- Base Unionism

- Bordigism

- Communist Left Inspired

- Cooperativism and Autogestion

- DeLeonism

- Environmentalism

- Fascism

- Feminism

- German-Dutch Communist Left

- Gramscism

- ICC and French Communist Left

- Islamism

- Italian Communist Left

- Leninism

- Liberism

- Luxemburgism

- Maoism

- Marxism

- National Liberation Movements

- Nationalism

- No War But The Class War

- PCInt-ICT

- Pacifism

- Parliamentary Center-Right

- Parliamentary Left and Reformism

- Peasant movement

- Revolutionary Unionism

- Russian Communist Left

- Situationism

- Stalinism

- Statism and Keynesism

- Student Movement

- Titoism

- Trotskyism

- Unionism

Regions

User login

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.